1Galgotias Institute of Management and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

2Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Management Studies and Research, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Most firms have been infusing environmental management practices in their organisational operations as green human resource management (GHRM). This study aims to validate the constructs under the GHRM in the Indian environment. The study conducted on four functions of GHRM reveals that green performance management, green compensation management, green health and safety and green involvement support an organisation in achieving its green goals. This study uses a two-stage methodology of data analysis by using AMOS. The current study explores the varied dimensions of organisational management, paving the way for future research on green human resource practices in the Indian diaspora.

Human resource management, environmental management, performance management, sustainable environment, green health and safety

Introduction

In the present scenario, debates on sustainability have led to the implementation of green practices in every sector (Aboramadan, 2022; Afum et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2019). Organisations must tackle environmental problems, which are a global concern and must change their strategies accordingly (Bahuguna et al., 2022; Paillé et al., 2014). The exclusivity and uniqueness of the human resources practices at a firm and their optimum utilisation help create a unique advantage over others. The organisations are now infusing green practices into the human resource department under the purview of green human resource management (GHRM). Moreover, environmentally sustainable management methods are linked with human resources through green environmental human resource management to combat rising environmental challenges (Tanova & Bayighomog, 2022). The changing times warrant the need to alter the concepts of human resource management concerning sustainable environmental practices (Paulet et al., 2021). The inclusion of GHRM is considered imperative for the successful application of sustainability practices (Ahmad, 2015). GHRM comprises a multitude of positive implications for firms, notably bringing in new hires and improving employee retention (Muster & Schrader, 2011), cutting expenses and gaining a competitive advantage (Carmona-Moreno et al., 2012), strengthening a firm’s overall performance in the environment (Kim et al., 2019), boosting overall effectiveness, improving the sustainability of the business and improving overall employee well-being and productivity (Gholami et al., 2016). GHRM practices promote environmentalism, further boosting employee morale and satisfaction (Mampra, 2013; Paulet et al., 2021). The sustainable operations formulating GHRM may also merge with the CSR initiatives of the firm as well.

A firm needs to ensure that its management strategies are guided by environmental guidelines and initiatives being put in place to combat environmental issues. This approach to green management needs to be embraced by organisations (Lee et al., 2009). When the varied human resource functions accompanied by sustainability are integrated with organisational strategies, it constitutes GHRM. Encouraging and fostering environmentally friendly attitudes among employees can be achieved by incorporating positive environmental values through the various dimensions of the company’s HR functions (Pellegrini et al., 2018).

In order to promote and encourage pro-environment performances by the employees, the new recruits should be accoladed through continuous reward systems acknowledging their environmental performances in the organisation.

Although few researchers did study varied theoretical aspects of GHRM in the Indian context, empirical studies conducted on GHRM practices in Indian organisations remain scant. Moreover, the majority of such research was confined to the Indian automobile sector (Chaudhary, 2019). Thereby, this research explores the significant aspects of GHRM across different industries in India. The scale used in the study has been adopted from Shah (2019), which was tested with the enlisted Pakistan Stock Exchange companies. Although, in the past, considerable literature has covered different aspects of human resource management. However, the more significant consensus remains that there is a dearth of studies focusing on the effectual application of GHRM strategies ensuring the fulfilment of sustainability objectives in the organisation (Ahmad, 2015). Earlier, GHRM was tested by using 21 items studied by Chaudhary (2019) by assessing the items developed by Dumont et al. (2017) and Tang et al. (2018). Furthermore, Shah (2019) developed a scale of 81 items measuring seven GHRM practices which our current study has assessed to test in the Indian environment.

This study aims to analyse corporations’ strategies to promote sustainable environmental management programmes by examining how they develop human resource policies and implement various processes related to GHRM. The data for this analysis were collected from organisations across multiple industries. This study has been conducted on various industries ranging from telecom, media, education, dairy sector and manufacturing sector. In the following sections of the study research design and the measures’ validation, a discussion of the findings and conclusions are presented.

Literature Review

After an extensive review of available literature on GHRM, researchers explored that corporates are developing HR policies for going green. Since 1990, several studies have been conducted examining an organisation’s environmental monitoring and policies (Hale, 1995).

HRM comprises four significant functions: motivation, staffing, training and development and maintenance (Decenzo et al., 2016). With the help of a literature review, an attempt has been made to align HRM functions with the Green approach.

Green Performance Management (GPM)

GPM is considered as a fundamental HRM practice to encourage sustainable operations and environmental development in an organisation. GPM aims to integrate different management processes for sustainable development to improve organisational performance. It is argued that an employee’s job performance should also be evaluated based on criteria formulated to measure his contribution to the green policies of the firm. Besides, the feedback interviews of the employees should focus on their involvement in green projects of the organisation (Opatha & Arulrajah, 2014). If the management emphasises including the employee’s contribution to the organisation’s sustainable practices as the appraisal criteria, it may entice them to adopt such practices at an advanced level. GPM invokes the use of natural resources whilst organising and executing organisational activities. In addition, it comprises conducting events assimilating the environmental objectives with the firm’s events. Tata Group has incorporated green information systems and auditing for measuring environmental performance and obtaining helpful information on environmental management.

Green Compensation and Reward System

In order to facilitate the smooth processing of the organisational activities and fulfilling environmental objectives, the firms can initiate a reward system for the employees. Using considerable compensation as a tool to acknowledge the efforts of the employees to meet their sustainability goals can help to boost their morale (Ahmad, 2015). As part of the management strategy, organisations are increasingly developing reward systems to promote environmentally sustainable programmes. According to a survey conducted by CIPD/KPMG in the UK, 8% of companies were providing awards and financial incentives for green behaviours (Phillips, 2009). These practices have been found to motivate employees to participate in eco-initiatives. It has been suggested that specific sustainable programmes should be incorporated into the compensation system, offering employees benefits that reward them for their behaviour change.

Payment elements can be linked to eco-performance, adding flexibility to the compensation system. Using monetary and non-monetary incentives to commemorate the green efforts of employees is imperative for organisational growth (Opatha & Arulrajah, 2014).

Green Health and Safety (GHS)

The organisations work in collusion with the government’s policies and the workers’ associations to ensure employees’ overall health and safety at the workplace. The management devises policies to reduce occupational injuries and health hazards at work. There have been a lot of focused studies on different approaches to improving Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) in the industry. Past researchers have investigated various occupational hazards affecting workers’ health and well-being (Aburumman et al., 2019; Samano-Rios et al., 2019). According to the International Labour Organisation, ‘We continue to live through a global health crisis and face ongoing OSH risks in the world of work, and hence we must move toward building a solid safety and health culture at all levels’ (Kim et al., 2016). The Green approach on OSH can help solve many work-related injuries due to stress and job-related sickness.

Green Employee Involvement

The involvement of green workers in GHRM can be defined as creating an environment that improves employee engagement and morale (Chaudhary, 2019). Employee engagement entails seeking the recommendation of the personnel for developing effective, sustainable approaches and policies for organisational development. Green engagement encourages continuous employee feedback to enhance the current environmental plans and strategies. Green employee engagement can motivate employees and enhance their cooperation in organisational growth. Organisations can consider employee involvement as a part of their CSR initiative, which also exhibits the employees’ commitment towards their work goals (Davies & Crane, 2010). Phillips (2009) says employee involvement in green HR practices can help prevent workplace pollution. One way to encourage employee involvement is by promoting and rewarding eco-intrapreneurs. Through their innovative mindset, they can use the existing financial, human and natural resources to add value to company products or services (Mandip, 2012). Employee involvement in organisational greening has been found to improve critical environmental management outcomes, primarily reducing waste and pollution at the workplace (Ansari et al., 2020; Carballo-Penela et al., 2022; Florida & Davidson, 2001).

Research Methodology

Measures

HRM functions can be mainly grouped into staffing, motivation, training and development and maintenance. GHRM consists of initiating and acknowledging the green performances of the employee and introducing training ideas to fulfil the firm’s environmental objectives. It involves informing employees of their sustainability-oriented workplace goals and rewarding them accordingly for the same (Clair et al., 1996). The organisation can measure and improve the green performance of the employees through non-monetary incentives. Training programmes aligning the employee objectives with the organisational goals can be initiated (Jabbour & Santos, 2008). The mentioned components of GHRM are classified under six main heads recruitment, training and development, performance appraisal, reward management, employment relations and exit (Cherian & Jacob, 2012; Renwick et al., 2008). Numerous studies asserted rewards systems and involvement, training and performance management, and recruitment and selection as essential practices under GHRM (Prasad, 2013; Sudin, 2011). Based on the varied definitions and components of GHRM, a list of dimensions were finalised for the study.

Proposed Dimensions

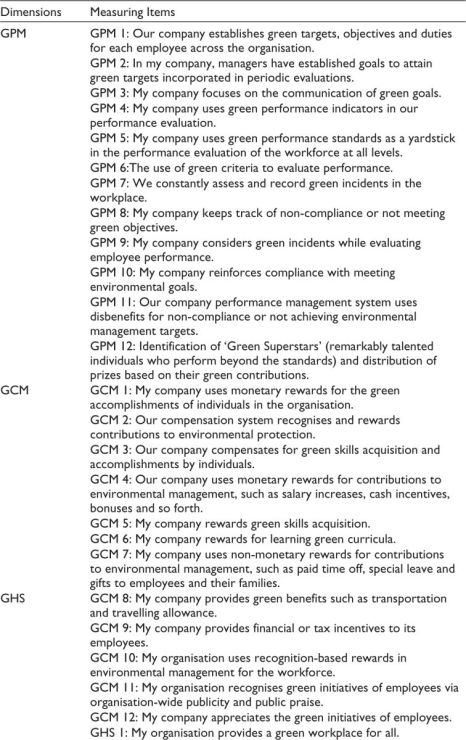

GHRM was assessed using 35 items taken from Shah (2019). The dimensions that have been considered for the study are GPM, Green Compensation Management (GCM), GHS and Green Involvement (GI). The items were measured using a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = Strongly disagree and 5 = Strongly agree. The dimensions and their measurement items are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Dimensions of GHRM with the Items.

Source: Items adapted from the study by Shah (2019).

Data Collection

The data were collected from different industries in India because it is one of the leading developing countries facing environmental pollution problems. Three cities (New Delhi, Agra and Gurugram) were chosen as the sampling frame.

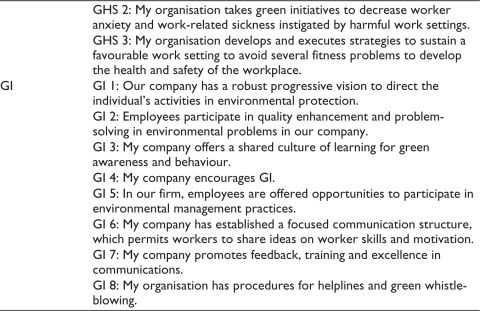

Individuals living in these areas are considered socio-environmentally conscious and are expected to be aware of prevailing green issues in the organisations. New Delhi (the capital of India) has been recorded as the highest polluted city in the country, followed by nearby places Gurugram and Agra. The data were collected from various industries across various sectors such as Automobile, Banking, Dairy, Education, Manufacturing, Media and Entertainment, Retail, Telecom, Service and Pharmaceutical. A questionnaire was developed using Google Forms and mailed to employees working at the managerial level. Respondents mainly comprised of top-level management, as senior management is expected to be involved in implementing various practices, including GHRM. The managerial level respondents comprised of Deputy General Manager (DGM), General Manager (GM), Senior Manager and middle-level managers. The study comprised of 573 responses after discarding the outliers. The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) sample comprised of 180 respondents (47 females and 133 males), and the CFA sample comprised 393, with 56.9% male participants and 43.1% female participants. Among the respondents, 11 (2.7%) were DGM, 30 (7.6%) were GM, 180 (45.8%) were Senior Managers and 172 (43.7%) were Managers. A total of 70.9% of respondents were postgraduates and 29% were graduates. Demographic details for study 2, that is, CFA, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Demographic Details of Respondents.

Data Analysis and Results

Study-1 Exploratory Factor Analysis

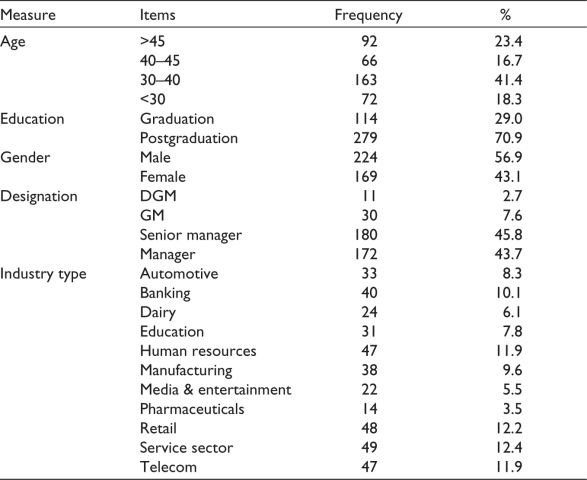

To explore the underlying dimensions of the scale, an EFA using principal component analysis (Hotelling, 1933) was performed on 180 respondents prior to final data collection. SPSS version 24 was used to operationalise EFA with Kaiser Normalisation (Kaiser & Rice, 1974).

The eigenvalue of 1 as a cutoff value was considered for the extraction of items. Hair et al. (2006) suggested that a cutoff value of 0.6 was used to retain the items. EFA results helped in the exploration of four underlying constructs, namely GPM, GCM, GHS and GI. None of the items had cross-loadings or was loaded on multiple factors.

The items were found to be loaded with sufficient loadings with their respective constructs. GPM1 had the highest loading (0.898), and the lowest loading was exhibited by GI8 (0.694)—none of the items loaded on multiple factors, indicating discriminant validity. The items loaded significantly, and the t-values (p < .001) indicated the construct’s unidimensionality. Table 3 summarises the factor loadings for the 35-item scale.

Table 3. Results of Exploratory Factor Analysis.

Study-2 Measurement Model Assessment (Confirmatory Factor Analysis)

First-order Analysis

Structural equation modelling was used to conduct the first-order analysis. The results in the first-order model for the four dimensions, GPM, GCM, GHS and GI, were analysed through the goodness-of-fit criteria. All the model-fit indices were CMIN/df = 1.536, RMSEA = 0.056, CFI = 0.95 and NFI = 0.928.

For first-order analysis, loadings of the first item in every dimension were set to 1.0 to standardise the results for the other items. GCM 5 (0.88) followed by GCM 6 (0.86), both the items got the highest loading. In contrast, the lowest loading was on that of GHS 1 (0.60). The highest correlation was between GPM and GI (r = 0.88) followed by GPM and GCM (r = 0.86) and GCM and GHS (r = 0.84). Therefore, the results showed that the correlation between the constructs is relatively good.

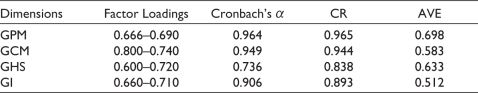

Reliability and Validity Analysis

The study’s construct reliability was assessed through Cronbach’s alpha (α) co-efficient for internal reliability and critical ratio (CR) for composite reliability (Awang, 2012). Cronbach’s alpha values were found to be greater than 0.7, depicting the internal reliability of the measurement scale. CR for the study was above the threshold value of 0.60, as reported by Hu and Bentler (1999), demonstrating the construct’s composite reliability. Both measures indicated that the scale had good reliability.

To prevent multicollinearity issues, discriminant validity must be assessed in any research involving latent variables. Fornell and Larcker’s criterion is used for the same (Ab Hamid et al., 2017). The convergent validity was confirmed by computing the average variance extracted (AVE) for the sub-constructs of the scale (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). AVE, which is greater than 0.50, is considered acceptable (Hu & Bentler, 1999). All the sub-constructs demonstrated AVE values greater than the traditional value of 0.50, indicating the convergent validity of the scale. Additionally, Chin et al. (1997) retorted that the factor loading of the items should be significant and greater than 0.60. The factor loadings of all the items were significant and greater than 0.60, further supporting the scale’s convergent validity (refer to Table 4).

Table 4. CR Values and Items Factor Loadings.

Source: Prepared by researcher.

Second-order Analysis

Second-order factor analysis was conducted by inserting a latent factor GHRM to understand the correlation between the four dimensions with the latent construct GHRM, all model-fit indices were applied to find the goodness of fit, and the values satisfied the criteria. Several indices of second-order analysis were more significant than in the first-order model (Doll et al., 1994). The goodness-of-fit values were above the threshold values with CMIN/df = 1.589, RMSEA = 0.058, CFI = 0.95 and NFI = 0.916. Therefore, the second-order model is a necessary test and better justifies GHRM as a second-order construct. For standardised factor loadings of all the items, the first item in each sub-construct was constrained to 1. The results show that the second-order analysis of GHRM is highly justified and explains the first-order analysis. GCM was loaded significantly with highest factor loading (please refer to Table 4) followed by GHS and GI, and the lowest loading was GHS (0.660–0.710).

Discussion

The findings revealed that GHRM comprised dimensions, such as performance management, compensation, employee involvement and employee health and safety. A 35-item scale can measure these functions. Many previous studies have been conducted on various other HR practices and functions (Mishra et al., 2014; Paillé et al., 2014; Renwick et al., 2008). However, this study has been conducted using the four effective HR practices functions because performance management, compensation, employee participation and health and safety represent sustainable and environmental practices of the employees at the workplace (Ojo & Raman, 2019). Shah (2019) developed a scale having dimensions such as GI, green recruitment and selection, GPM, green labour relations and green training and development. The research confirmed that GHRM would connote performance management as the GHRM dimension since training employees and tracking their progress concerning organisational goals remain imperative for GHRM. Involving employees in the green practices of the firm and honing their skills and abilities to achieve the organisational and personal environmental goals makes GHRM more effective. The study also validates the inclusion of GCM in GHRM. Motivating the employees for timely completion of their green tasks by granting them continual rewards would constitute an essential component of GHRM. Since GHRM entails invoking the employees’ interests in environmental practices, compensating them through monetary and non-monetary incentives can keep the employees enthusiastic about participating in GHRM practices. The research study corroborates that GHRM would also include GHS, thereby inducing the management to initiate health and safety programmes for the employees which guarantee a robust green workplace.

Implications

Theoretical Implications

The present research also discusses some theoretical implications. To the best of our knowledge, this remains one of the first studies to validate a developed GHRM scale in the Indian environment. However, many studies have empirically developed scales using the various dimensions of GHRM and have also been tested in other countries and industries. However, no previous studies have validated the scale in Indian industries. Therefore, we specifically address the research gap of testing the scale in industries such as India’s textiles, telecom, dairy and media & entertainment sectors. The present study results can be generalised to emerging economies where a sustainable green environment remains an issue of concern.

The various constructs of the above study have been thoroughly analysed with the help of an extensive literature review, and their theoretical implications are thus explained. This study adds to the existing body of knowledge of GHRM by validating the components which establish the environmental management of the employees in an organisation. The study has examined the varied tenets of the GHRM, which help organisations convert their employees into a green workforce in order to achieve environmental sustainability goals. The study revealed that GPM should be included in the GHRM as the construct, which involves apprising employees of their green objectives and laying down plans to help them achieve these objectives. Since GHRM entails invoking the employees’ interests in environmental practices, compensating them through monetary and non-monetary incentives through GCM can keep the employees enthusiastic about participating in GHRM practices. The study also supported the incorporation of GI in the scale while measuring GHRM. In order to successfully implement the GHRM practices, the organisation ought to communicate the firm’s vision concerning environmental sustainability to its employees. Participation in the GHRM practices can only be ensured by encouraging the employees to seek knowledge about green practices and environmental behaviour at work to keep them involved and inspired in green work life. GHRM cannot exclude health and safety policies which help the organisation improve the overall productivity of their employees by creating a stress-free wholesome working environment for them.

Managerial Implications

The findings emphasise that organisations must inculcate and develop an understanding of green competencies among their employees. In GPM, employees must be assessed based on attaining green goals. These green goals can only be achieved when the organisation sets up green objectives for all its workforce (Clair et al., 1996). Such objectives can help the employees to align their behaviours accordingly. GCS is an organisation’s strategic approach to encouraging employees to attain sustainable green goals (Jyoti, 2019). According to Karami (2013), a compensation system, preferably a non-financial one, would constructively impact the employees’ performance. Indian organisations should strive to create an environment that helps employees to work in a stress-free and safe environment and attain GHS. Our findings also reveal that GHS correlates highly with GHRM at 0.93. GI, such as employees’ participation in environmental decisions, is also an essential dimension of GHRM. For effective implementation of environmental strategies, the participation of the employees in the environmental processes and activities undertaken by the firm is imperative. Engaging employees with the firm’s sustainability initiatives remain challenging for the firms (Haddock-Millar et al., 2016; Singh et al., 2020). The results also show the highest correlation between GHRM with GI. Policies related to employee engagement towards environmental concern helps in motivating employees. Such policies related to employee engagement towards environmental concerns motivate employees (Niati et al., 2022).

Limitations and Future Research

The study was conducted to assess the different dimensions of the GHRM in an emerging economy; however, the study did face a few limitations. No study is without its limitations, but the limitations serve as an avenue for further research. First, the study had confined itself to studying specific dimensions of the GHRM construct, and future research may also explore the impact and significance of other dimensions of GHRM. Second, the research findings point out that there can be other contexts in which the study could be conducted. The study could be conducted by linking the concept of GHRM with different functional departments such as Operations, Marketing and Finance.

Lastly, the research did not include several HR dimensions such as green recruitment, green training and development which may provide an exciting insight into the study. Future research studies investigate these factors to have an insightful and extensive understanding of GHRM in India. Thus, future research could continue to dig deeper to understand the multidimensional nature of GHRM.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ab Hamid, M. R., Sami, W., & Sidek, M. M. (2017, September). Discriminant validity assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 890(1), 012163.

Aboramadan, M. (2022). The effect of green HRM on employee green behaviors in higher education: The mediating mechanism of green work engagement. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 30(1), 7–23.

Aburumman, M., Newnam, S., & Fildes, B. (2019). Evaluating the effectiveness of workplace interventions in improving safety culture: A systematic review. Safety Science, 115, 376–392.

Afum, E., Agyabeng-Mensah, Y., Opoku Mensah, A., Mensah-Williams, E., Baah, C., & Dacosta, E. (2021). Internal environmental management and green human resource management: significant catalysts for improved corporate reputation and performance. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 28(10), 3074–3101.

Ahmad, S. (2015). Green human resource management: Policies and practices. Cogent Business & Management, 2(1), 1030817.

Ansari, N. Y., Farrukh, M., & Raza, A. (2021). Green human resource management and employees pro-environmental behaviours: Examining the underlying mechanism. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(1), 229–238.

Awang, Z. (2012). Research methodology and data analysis second edition. UiTM Press.

Bahuguna, P. C., Srivastava, R., & Tiwari, S. (2022). Two-decade journey of green human resource management research: A bibliometric analysis. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 30(2). https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-10-2021-0619

Carballo-Penela, A., Ruzo-Sanmartín, E., Álvarez-González, P., & Saifulina, N. (2022). A systematic literature review of green human resource management practices and individual and organizational outcomes: The case of pro-environmental behaviour at work. In: Paillé, P. (eds) Green Human Resource Management Research, 79–115, Sustainable Development Goals Series. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06558-3_5.

Carmona-Moreno, E., Céspedes-Lorente, J., & Martinezdel-Rio, J. (2012). Environmental human resource management and competitive advantage, Management Research, 10(2), 125–142.

Chaudhary, R. (2019). Green human resource management in Indian automobile industry. Journal of Global Responsibility, 10(2), 161–175.

Cherian, J., & Jacob, J. (2012). A study of green HR practices and its effective implementation in the organisation: A review. International Journal of Business and Management, 7(21), 25.

Chin, W. W., Gopal, A., & Salisbury, W. D. (1997). Advancing the theory of adaptive structuration: The development of a scale to measure faithfulness of appropriation. Information Systems Research, 8(4), 342–367.

Clair, J. A., Milliman, J., & Whelan, K. S. (1996). Toward an environmentally sensitive eco-philosophy for business management. Industrial & Environmental Crisis Quarterly, 9(3), 289–326.

Davies, I. A., & Crane, A. (2010). Corporate social responsibility in small-and medium-size enterprises: Investigating employee engagement in fair trade companies. Business Ethics: A European Review, 19(2), 126–139.

DeCenzo, D. A., Robbins, S. P., & Verhulst, S. L. (2016). Fundamentals of human resource management. John Wiley & Sons.

Doll, W. J., Xia, W., & Torkzadeh, G. (1994). A confirmatory factor analysis of the end-user computing satisfaction instrument. MIS Quarterly, 18(4), 453–461.

Dumont, J., Shen, J., & Deng, X. (2017). Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Human Resource Management, 56(4), 613–627.

Florida, R., & Davison, D. (2001). Gaining from green management: Environmental management systems inside and outside the factory. California Management Review, 43(3), 64–84.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Gholami, H., Rezaei, G., Saman, M. Z. M., Sharif, S., & Zakuan, N. (2016). State-of-the-art green HRM system: Sustainability in the sports center in Malaysia using a multi-methods approach and opportunities for future research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 124, 142–163.

Haddock-Millar, J., Sanyal, C., & Muller-Camen, M. (2016). Green human resource management: a comparative qualitative case study of a United States multinational corporation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(2), 192–211.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson.

Hale, M. (1995). Training for environmental technologies and environmental management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 3(1–2), 19–23.

Hotelling, H. (1933). Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. Journal of Educational Psychology, 24(6), 417.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Jabbour, C. J. C., & Santos, F. C. A. (2008). The central role of human resource management in the search for sustainable organisations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(12), 2133–2154.

Jyoti, K. (2019). Green HRM–people management commitment to environmental sustainability. In Proceedings of 10th International Conference on Digital Strategies for Organisational Success. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3323800

Kaiser, H. F., & Rice, J. (1974). Little jiffy, mark IV. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 34(1), 111–117.

Karami, A., Dolatabadi, H. R., & Rajaeepour, S. (2013). Analysing the effectiveness of reward management system on employee performance through the mediating role of employee motivation case study: Isfahan Regional Electric Company. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3(9), 327.

Kim, Y. J., Kim, W. G., Choi, H. M., & Phetvaroon, K. (2019). The effect of green human resource management on hotel employees’ eco-friendly behavior and environmental performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76, 83–93.

Kim, Y., Park, J., & Park, M. (2016). Creating a culture of prevention in occupational safety and health practice. Safety and Health at Work, 7(2), 89–96.

Lee, A. H., Kang, H. Y., Hsu, C. F., & Hung, H. C. (2009). A green supplier selection model for high-tech industry. Expert Systems with Applications, 36(4), 7917–7927.

Mampra, M. (2013, January). Green HRM: Does it help to build a competitive service sector? A study. In Proceedings of 10th AIMS International Conference on Management, 3(8), 1273–1281.

Mandip, G. (2012). Green HRM: People management commitment to environmental sustainability. Research Journal of Recent Sciences, 1(ISC-2011), 244–252.

May, D. R., & Flannery, B. L. (1995). Cutting waste with employee involvement teams. Business Horizons, 38(5), 28–39.

Mishra, R. K., Sarkar, S., & Kiranmai, J. (2014). Green HRM: Innovative approach in Indian public enterprises. World Review of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development, 11(1), 26–42.

Muster, V., & Schrader, U. (2011). Green work-life balance: A new perspective for Green HRM. German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift für Personalforschung, 25(2), 140–156.

Niati, A., Rizkiana, C., & Suryawardana, E. (2022). Building employee performance through employee engagement, work motivation, and transformational leadership. International Journal of Social Science, 2(1), 1153–1162.

Ojo, A. O., & Raman, M. (2019). Role of green HRM practices in employees’ pro-environmental IT practices. In New knowledge in information systems and technologies: Volume 1 (pp. 678–688). Springer International Publishing.

Opatha, H. H. D. N. P., & Arulrajah, A. A. (2014). Green human resource management: A simplified general reflections, International Business Research, 7(8), 101–112.

Paillé, P., Chen, Y., Boiral, O., & Jin, J. (2014). The impact of human resource management on environmental performance: An employee-level study. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(3), 451–466.

Paulet, R., Holland, P., & Morgan, D. (2021). A meta-review of 10 years of green human resource management: Is Green HRM headed towards a roadblock or a revitalisation? Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 59(2), 159–183.

Pellegrini, C., Rizzi, F., & Frey, M. (2018). The role of sustainable human resource practices in influencing employee behavior for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(8), 1221–1232.

Phillips, Jack J. (2009). Accountability in human resource management: Connecting HR to business results. Routledge.

Prasad, R. S. (2013). Green HRM-partner in sustainable competitive growth. Journal of Management Sciences and Technology, 1(1), 15–18.

Renwick, D., Redman, T., & Maguire, S. (2008). Green HRM: A review, process model, and research agenda. University of Sheffield Management School Discussion Paper, 1(1), 1–46.

Samano-Rios, M. L., Ijaz, S., Ruotsalainen, J., Breslin, F. C., Gummesson, K., & Verbeek, J. (2019). Occupational safety and health interventions to protect young workers from hazardous work–A scoping review. Safety Science, 113, 389–403.

Shah, M. (2019). Green human resource management: Development of a valid measurement scale. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(5), 771–785.

Singh, S. K., Del Giudice, M., Chierici, R., & Graziano, D. (2020). Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 150, 119762.

Sudin, S. (2011, June). Strategic green HRM: A proposed model that supports corporate environmental citizenship. In International Conference on Sociality and Economics Development. International Proceedings of Economics Development and Research, 10, 79–83.

Tang, G., Chen, Y., Jiang, Y., Paille, P., & Jia, J. (2018). Green human resource management practices: Scale development and validity. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 56(1), 31–55.

Tanova, C., & Bayighomog, S. W. (2022). Green human resource management in service industries: The construct, antecedents, consequences, and outlook. The Service Industries Journal, 42(5–6), 412–452.