1 Faculty of Commerce, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

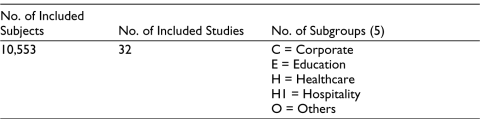

Workplace ostracism (WO) poses a significant threat to organizational well-being, with implications for employee turnover intention (TI). This meta-analysis explores the relationship between WO and TI across 32 studies involving 10,553 participants from diverse sectors and countries. The findings reveal a significant positive correlation (r = 0.31) between WO and TI, indicating that employees experiencing ostracism are more likely to contemplate leaving their jobs. Despite substantial heterogeneity (I² = 93.07%), moderators such as participants’ average age and the percentage of females show limited impact on the relationship. Sector-based subgroup analysis suggests a consistent impact of WO on TI across various employment sectors. The study provides practical insights for managers, emphasizing the importance of addressing WO to enhance employee retention and well-being. Recommendations include fostering inclusive cultures and implementing targeted interventions to mitigate the negative effects of ostracism in diverse organizational settings.

Workplace ostracism, turnover intention, meta-analysis, systematic literature review, moderators

Introduction

Employees spend a significant part of their lives at the workplace, and the experience of being ignored or excluded, known as workplace ostracism (WO), can have profound consequences. WO is defined as “the degree to which an individual perceives that he or she is being ignored or excluded by others” (Ferris et al., 2008), and it has implications for both individuals and organizations (Howard et al., 2020). Various terms, such as isolation (Williams, 2000; 2007), rejection (Prinstein & Aikins, 2004), social exclusion (Twenge et al., 2002), being out of the loop (Jones et al., 2009), and abandonment (Baumeister et al., 1993), can be used interchangeably with the term WO. Surveys indicate that 19%–66% of employees experience workplace isolation (Fox & Stallworth, 2005). Being part of an organization is linked to job success, while social exclusion is associated with organizational issues and intentions to leave (Ferris et al., 2008).

This unique meta-analysis aims to uncover trends in the relationship between WO and turnover intention (TI). Past research presents conflicting results: Some studies report a strong positive correlation, while others find no significant relationship (Penhaligon et al., 2013; Lim et al., 2016). To reconcile these inconsistencies, we draw on Social Identity Theory (SIT; Tajfel & Turner, 1982), Conservation of Resources Theory (COR theory; Hobfoll, 1989), and Belongingness Theory (BT; Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Additionally, a meta-analysis clarifies conflicting findings and explores potential moderators using the Meta Essential tool. Our decision to focus on TI, rather than actual turnover behavior, is practical and aligned with common research practices. Moreover, Steel and Ovalie’s (1984) meta-analysis reveals a robust association between TI and actual turnover. It emphasizes that TI are more effective predictors of turnover than affective variables such as job satisfaction, career satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Therefore, in our study, we opted for TI as the dependent variable rather than actual turnover, considering the reasons mentioned above.

WO is a significant concern, impacting employee well-being and organizational performance. This study addresses the pervasive impact of WO on employees and organizations, including issues of TI, team dynamics, and overall workplace morale. Despite growing awareness of the detrimental effects of WO, a comprehensive understanding of its nuanced relationship with TI remains elusive. Our meta-analysis contributes to this understanding, offering insights into organizational practices and interventions to cultivate healthier workplaces.

Our study identified a crucial gap in the literature regarding the relationship between WO and TI. While prior research extensively explores this association, a comprehensive understanding of potential moderating factors remains underexplored. To address this gap, our study employs a moderator analysis, delving into contextual and individual-level factors influencing the strength or direction of the observed relationship. By systematically examining potential moderators, we aim to offer valuable insights beyond the traditional understanding of the WO–TI association, contributing to a more nuanced perspective for researchers and practitioners. This approach enhances the comprehensiveness of our study within the broader context of advancing knowledge in the field.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Workplace Ostracism

WO is a prevalent issue that many employees face (Ferris et al., 2008). It involves employees being deliberately excluded from social interactions and opportunities, often involving mistreatment (Harvey et al., 2018). This exclusion can be a result of intentional offense, forbidding, suspension, or intimidation, causing individuals to feel isolated and discouraging others from associating with them (Williams & Gerber, 2004). Surprisingly, WO is a common occurrence in workplaces, yet there is limited research on its causes (Hitlan et al., 2006). In a workplace, co-workers and supervisors provide social and emotional support that fulfills individuals’ needs for social connection and recognition. WO can take two forms: supervisor ostracism and co-worker ostracism. However, there is limited research on how these forms of ostracism affect employee behavior.

Supervisor Ostracism

Supervisor ostracism (SO) refers to a supervisor’s actions, which include ignoring, avoiding, or neglecting an employee, ultimately eroding the individual’s sense of communal status and dignity (Shapiro et al., 1994). Supportive leadership, on the other hand, has been shown to have positive effects, such as reducing stress and enhancing overall job performance (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). When employees experience SO, it results in detrimental effects on their confidence, competence, and overall well-being. This negative impact often leads to emotional overwhelm, as highlighted by the work of Halbesleben and Bowler (2005).

Co-worker Ostracism

Co-worker ostracism (CO) is described as an employee’s perception of how much they are ignored by their colleagues and kept silent, excluded from the conversation, or excluded from group activities. CO can also be interpreted as “the degree to which a person believes he or she is being ignored or excluded by others” (Ferris et al., 2008). According to Robinson et al. (2013), when the act of engaging another member of the organization is socially appropriate, but an individual or group fails to take the action, it is known as CO.

Turnover Intention

TI, as defined by Thoresen et al. (2003), is an expression of an employee’s desire to leave their current organization (Price, 2001). TI refers to the desire to quit one’s job due to workplace isolation (Bothma & Roodt, 2013), actively seeking alternative employment (Turkoglu & Dalgic, 2019), or due to dissatisfaction, employees seek new job opportunities (Mobley et al., 1978). High turnover negatively affects company performance by disrupting operations (Setyanto & Hermawan, 2018). In response, organizations prioritize employee retention as a competitive survival strategy (Lockwood, 2006). Employees contemplating leaving their jobs undergo psychological processes such as assessing job satisfaction, exploring options, and weighing the pros and cons (Mobley, 1977). Employee turnover incurs significant organizational costs such as recruitment, training, and potential errors during adjustment (Yang, 2008). It can lead to stress, psychological issues, and burnout for both organizations and employees (Dysvik & Kuvaas, 2010), compromising service quality, especially during peak periods (Choi, 2006).

Workplace Ostracism and Turnover Intention

Here, we suggest that experiencing WO increases the likelihood of TI. This connection is based on three underlying reasons.

Conservation of Resource Theory

According to the COR theory by Hobfoll (2001), people are naturally inclined to build, develop, and safeguard their possessions, jobs, respect, and financial assets. The COR theory by Hobfoll (1989) posits that individuals strive to preserve and acquire resources to meet personal and professional goals. The COR theory proposes that when employees feel left out or excluded, they are likely to experience a reduction in their available resources (Turkoglu & Dalgic, 2019). This heightened vulnerability can lead to increased anxiety and a decrease in positive work attitudes (Leung et al., 2011). Workplace resource loss leads to emotional distress and psychological strain, which are significant contributors to burnout (Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998). As burnout intensifies, employees may feel overwhelmed, which in turn diminishes their commitment, increases the likelihood of contemplating job departure, and ultimately contributes to higher turnover rates (Farasat et al., 2021). Empirical studies, such as Kim and Stoner (2008), establish a link between burnout and increased turnover. Research indicates that WO leads to higher TI among affected employees (Ferris et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2016).

Belongingness Theory

Belongingness is a basic human need (Allen, 2020). According to Baumeister and Leary (1995), BT emphasizes the essential desire for meaningful and lasting interpersonal relationships. The BT suggests that ostracism threatens the inherent need for belonging, which is crucial for success, safety, and survival (Scott et al., 2014). Not feeling like you belong can result in physical, emotional, and social distress. People who experience exclusion attempt to ease the emotional distress it causes (Wang et al., 2021). Additionally, WO, seen as an unfavorable work environment factor, can make individuals feel unwelcome, leading to a separation between the person and the organization (Lyu & Zhu, 2019). Studies using scenarios, like ball-tossing experiments, show that ostracized individuals prefer working alone or with a new group rather than with the one that excluded them (Williams, 2007). O’Reilly et al. (2015) found that ostracized employees are more inclined to leave their positions compared to those who feel included.

Social Identity Theory

SIT suggests that the way people see themselves and connect with others influences their attitudes and actions (Tajfel, 1978). The literature on socialization suggests that individuals are more likely to form and maintain favorable relationships within an organization when their values match those of the organization (Brewer & Gardner, 1996). This implies a sense of belonging and identification with the organization and its members, aligning with SIT (Tajfel, 1978). Conversely, employees whose values do not align may face social isolation, strengthening their feelings of being outsiders. According to SIT, being excluded at work diminishes crucial aspects like connection, respect, control, and a sense of meaningful existence, which are vital for organizational well-being (Kim & Ishikawa, 2021). WO unofficially undermines the authority, independence, and responsibilities that an individual should rightfully receive from the organization. This prevents the person from forming a psychological connection to the organization or group (Williams & Sommer, 1997), hinders the ability to establish a meaningful presence through their work, and results in TI among affected employees (Williams et al., 1998).

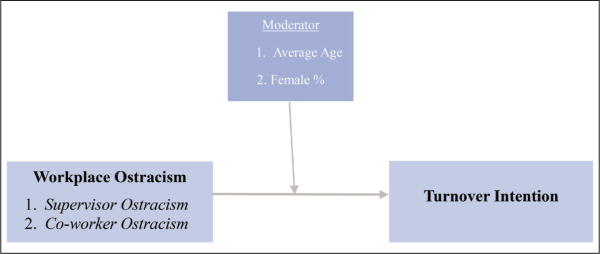

Based on the COR theory, BT, and SIT, this study hypothesizes that WO contributes to increased TI (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proposed Model of the Association Between WO and TI.

H1: WO is positively associated with TI.

Meta-analytical Review of the Studies

This study employed a meta-analysis based on Borenstein et al. (2009) methodology and followed PRISMA guidelines (Tikito & Souissi, 2019) for a systematic review. Pearson correlation coefficients measured the effect size in each study, interpreted using Cohen’s benchmarks (Cohen, 1992). Random effects model calculated sample-weighted average correlations. Forest plots visually depicted WO and TI correlations. Homogeneity analysis utilized Q and I2 statistics to assess study similarity and heterogeneity. Significant Q-values indicated heterogeneity, with I2 quantifying differences among effect sizes (Borenstein et al., 2009).

Moderators for the Study

Past research has indicated that specific individual characteristics, such as age and gender, might be influenced by WO (Peng & Salter, 2021). This study aims to explore the potential impact of average age and the percentage of females on WO–TI relationships in organizational settings.

Average Age

Teenagers may be more affected by ostracism due to the crucial role of peer acceptance in emotional regulation during adolescence (Guyer et al., 2014). While ostracism impacts everyone, adolescents and emerging adults may be more sensitive to it than older individuals (Pharo et al., 2011). Research suggests that adolescents experience more significant emotional effects from ostracism compared to adults (Sebastian et al., 2010). In our current study, we are exploring potential age-related differences in the impact of WO, considering factors such as inexperience and sensitivity to social dynamics among younger individuals.

Female Percentage

Ouyang et al. (2015) propose that women value mutual support and positive relationships. Social role theory suggests that gender differences in behavior stem from societal structures, leading to distinct psychological adaptations (Eagly, 1987; Eagly & Wood, 1999). Women are more susceptible to the challenges of WO (Bashir et al., 2024). Gender variations may influence how individuals perceive and cope with ostracism, potentially resulting in different reactions between men and women. The current study considers the female percentage as a moderator in exploring the relationship between WO and TI.

Methodology

Literature Search

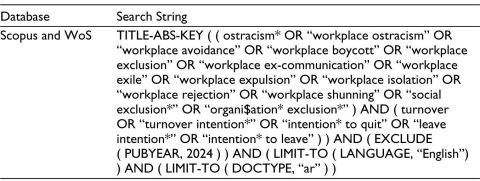

To conduct a comprehensive literature review, the authors extensively searched two electronic databases, Scopus and Web of Science (WoS), specifically targeting publications up to the year 2023. The search focused on the abstracts, titles, and keywords of studies that exhibited a correlation between WO and TI. The search was conducted on January 2024, using a search string (see Table 1) on both databases, leading to the identification of 65 records from Scopus and 74 records from WoS.

Table 1. Database and Search String Used for Data Retrieval.

Source: Scopus (www.scopus.com) & Web of Science (www.webofscience.com).

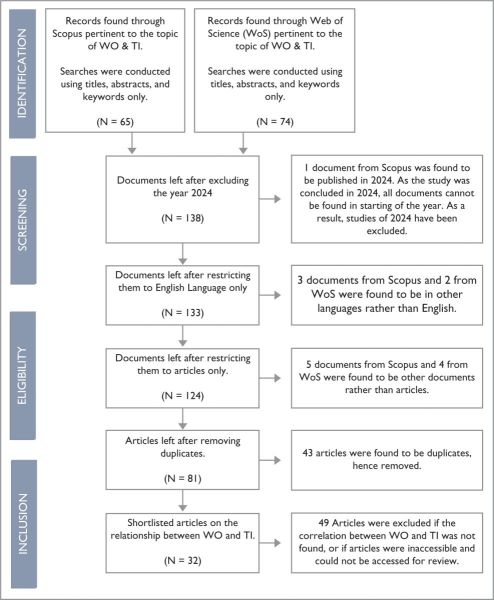

Criteria of Inclusion and Exclusion

Following this initial search, the authors implemented inclusion and exclusion criteria, with a particular emphasis on relevance to the meta-analysis. As the study was being conducted at the beginning of 2024, documents from the year 2024 were excluded, as it was deemed impractical to include all studies from that year. Consequently, the exclusion of 2024 led to 64 remaining documents from Scopus and 74 documents from WoS. Through additional refinement, restricting the search to publications in the English language, the count was further reduced to 61 from Scopus and 72 documents from WoS. Subsequently limiting the search to articles resulted in 56 from Scopus and 68 articles from WoS. After a meticulous screening process, only 32 studies met the predefined criteria and were included in the comprehensive review (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Flow Chart of Retrieval and Selection of Articles.

Software Used for the Analysis

In this study, we used Meta-Essential software for the analysis. A Meta-Essential is a tool used for calculating the overall correlation or effect size across multiple studies on a particular topic. It involves combining and analyzing data from various studies to derive a more comprehensive and robust estimate of the relationship between variables.

Scale Level Differences in the Study

In our study, we considered and handled differences in measurement scales used across studies. WO and TI are often assessed on various scales, introducing potential comparability challenges. Different studies may use Likert scales with different response options or categorical scales. Despite these variations, our meta-analysis addresses this issue using statistical methods like the Fisher’s Z transformation. This technique standardizes correlation coefficients measured on different scales, enabling us to combine and analyze them effectively. Recognizing and accommodating these scale differences is crucial for obtaining accurate insights from the collective research on WO and TI.

Transformation of the Variables (Fishers Z Transformation)

The transformation applied in this study is Fisher’s Z transformation. This transformation involves converting correlation coefficients (r) into a different scale by taking the arctangent of the correlation coefficient. The mathematical formula for the Fisher’s Z transformation is Z = 0.5 * ln((1 + r)/(1 – r)). This method stabilizes variance, normalizes the distribution of correlation coefficients, and is commonly used in meta-analytic studies, especially when dealing with correlation data. The purpose is to enhance the accuracy and appropriateness of statistical procedures in meta-analysis by creating a more suitable scale for aggregating correlation coefficients.

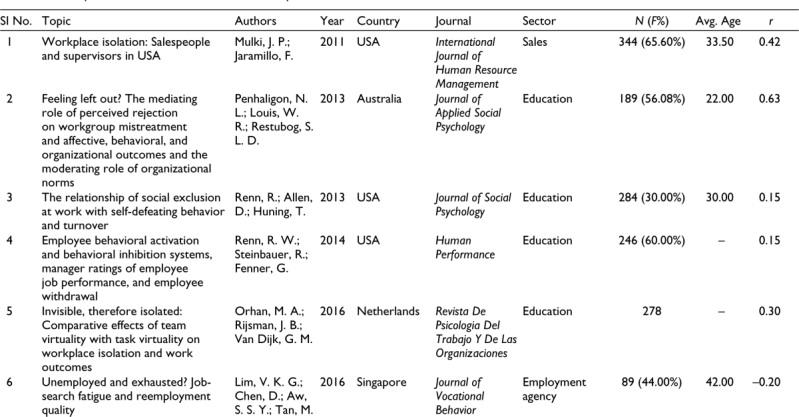

Coding of Studies

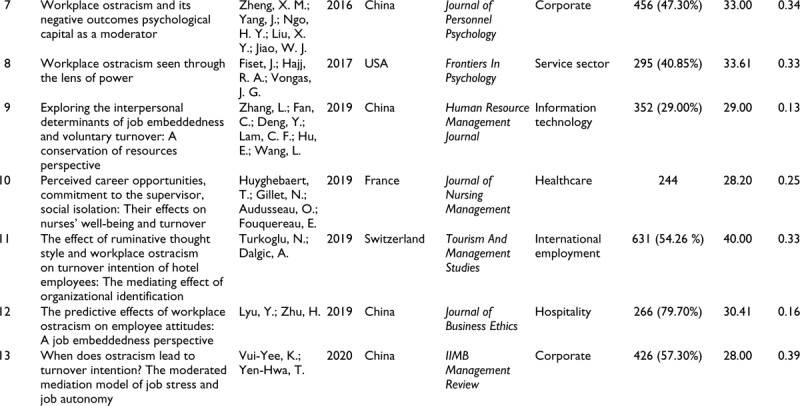

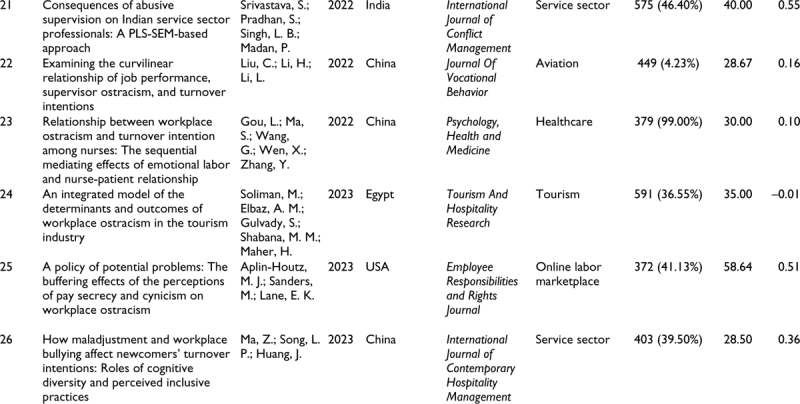

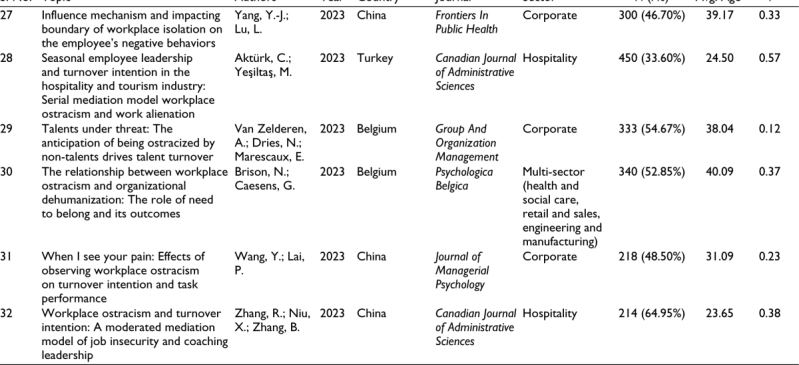

After removing the excluded studies, the remaining studies were carefully examined and categorized. The information extracted included authors, the title of the study, publication year, country name, journal name, the sector where the survey was carried out, sample size denoted by “N,” the percentage of females denoted by “F%,” the average age of the participants, and the correlation coefficient denoted by “r” (refer to Table 2).

Table 2. Descriptions of Included Studies for Meta-analysis.

Data Assumptions and Decision Rule

To make sure our meta-analysis is trustworthy and easy to understand, we have carefully adhered to well-established and standardized procedures. This helps to minimize any difficulties that might arise from tough decision-making situations. Our approach is strategic and focused on making the analysis strong and reliable, which in turn boosts the trustworthiness of our results. In this study, we have tackled concerns related to judgment by thoroughly addressing specific issues to ensure the quality of our research.

Missing Data

To address missing data, the researchers made assumptions to estimate the participants’ average age. They established upper and lower age limits using available information and used these limits to calculate the mean age. These assumptions helped fill data gaps and calculate the average age parameter.

Female Percentage

In cases where studies did not directly mention the female percentage but provided the male percentage, we calculated the female percentage by subtracting the male percentage from 100% (i.e., the total percentage of male and female participants).

Correlation

In some studies, WO was subdivided, and correlations were provided separately. In these cases, researchers calculated the average of these correlations and treated it as the overall correlation.

In cases where multiple studies were included in a single paper, researchers calculated the average of all correlation values within each study. This decision is based on the assumption that each study contributes unique insights into the relationship between variables, and averaging correlation values within each study helps in synthesizing the findings effectively.

Average Sample Size

In instances where several studies were encompassed within a single paper, leading to varying sample sizes, we computed the arithmetic mean or average of all the reported sample sizes within each study.

Quality Assessment

To ensure the reliability of our meta-analysis, a meticulous quality assessment was conducted, employing well-established tools and methodologies. The researchers followed a systematic literature review (SLR) process thrice, and searches consistently identified 32 papers, ensuring the inclusion of relevant studies. In assessing the quality of the selected studies, particular attention was given to the correlation coefficient between WO and TI. Scopus and WoS stand as two globally renowned and competitive citation databases. Researchers from an increasingly diverse array of countries, regions, and knowledge domains are engaging with these databases (Zhu & Liu, 2020). Consequently, the chosen papers are of high quality, given their extraction from the two pertinent databases.

Results

Descriptive Statistics/Description of Studies

In Table 2, a comprehensive meta-analysis is presented, encompassing 32 experimental studies involving a total of 10,553 participants from 12 different countries. Notably, 12 studies were conducted in China, 6 in the United States of America, 3 in Turkey, and 2 each in India and Belgium. Additionally, countries such as Australia, the Netherlands, Singapore, France, Switzerland, Korea, and Egypt contributed one article each to the meta-analysis. The majority of the studies were carried out in China. The professional backgrounds of the respondents were diverse, encompassing various sectors such as corporate, hospitality, healthcare, service sector, education, and others. This diversity in the participant pool enhances the generalizability of the findings. The meta-analysis included studies conducted between 2011 and 2023, covering a period of 13 years. The number of participants in these studies varied, ranging from 89 to 631 people, with an average of 360 participants. The average age of the participants across these studies was found to be 31.60 years. The reported correlation coefficients or effect sizes in the studies had a range of –0.20 to 0.60, indicating diverse strengths and directions of the relationships under investigation.

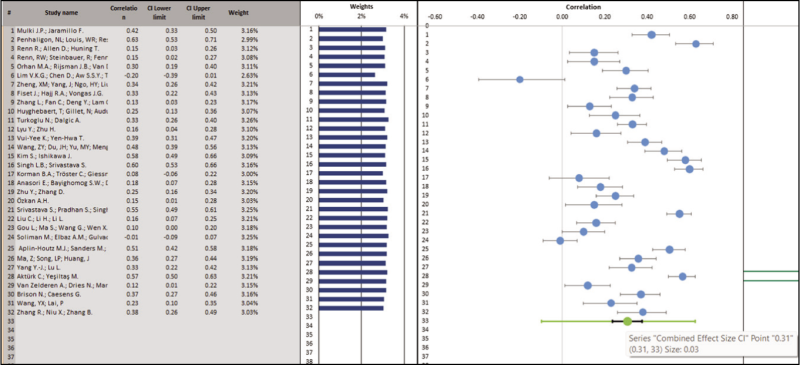

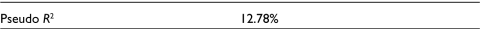

Overall Effect Size of WO and TI

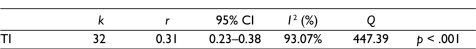

The forest plot in Figure 3 visually summarizes the relationship between WO and TI across various studies. The plot reveals a positive and significant association, indicating that when employees experience exclusion or neglect at work, there is an increased likelihood of contemplating job departure. The overall impact size, denoted as “r = 0.31” in Table 3, represents the strength and direction of this relationship. The positive sign signifies a consistent positive association across studies. Table 3 provides additional details, including the number of studies (k), confidence interval (95% CI: 0.23–0.38), high heterogeneity (I² = 93.07%), and statistical significance (p < .001), offering a comprehensive understanding of the robustness and consistency of the observed relationship in the meta-analysis.

Figure 3. Forest Plot on WO and TI.

Table 3. Meta-analysis of Workplace Ostracism and Turnover Intention.

Heterogeneity and Moderator Analysis

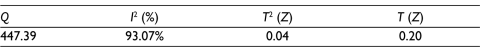

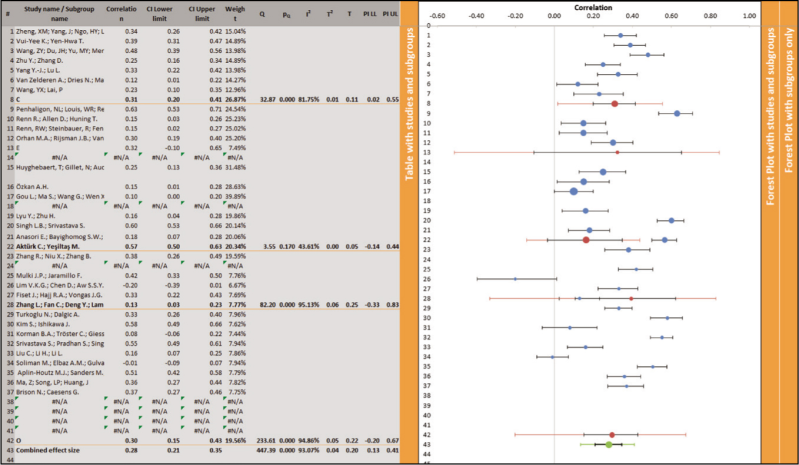

The I² statistic in Table 4 reveals substantial heterogeneity (I² = 93.07%) in the connection between WO and TI across the 32 studies. This suggests that there are likely factors influencing the relationship beyond what is accounted for by the overall effect size of 0.31. To explore potential moderators, a moderator analysis was undertaken on the 32 studies. Two variables were considered: participants’ average age and the percentage of females. Notably, three studies were excluded from the average age analysis due to missing data on participants’ average age. This process was repeated for the analysis of the percentage of females, excluding four studies due to missing data on the female percentage. The analytical approach involved using Q-range statistics and conducting subgroup analysis based on the sector of employees. These methods help in understanding if there are specific characteristics (such as age or gender distribution) that might explain the observed heterogeneity in the relationship between WO and TI across the studies.

Table 4. Heterogeneity Analysis.

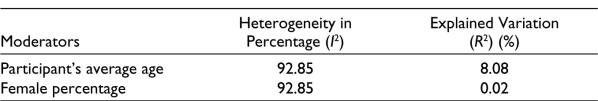

Participants’ Average Age and Female Percentage as Moderators

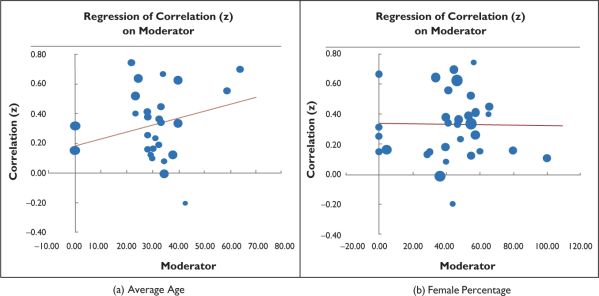

In Table 5, researchers looked at how the average age of participants and the percentage of women in the studies might explain this variability. Figure 4a shows a graph with the average age of participants on the horizontal axis and correlation values on the vertical axis. Figure 4b shows a similar graph but with the percentage of women on the horizontal axis. The results of the meta-regression analysis, represented by R² values, indicate that the average age of participants has a small impact (8.08%) on the relationship between WO and TI. In simpler terms, the age of the participants plays a minor role in how WO is connected to TI. On the other hand, the percentage of female participants did not have a significant impact on the relationship between WO and TI (R² of 0.02%).

Figure 4. Meta-regression Depicts the Role of Participants’ (a) Average Age and (b) Female Percentage as Moderators in the Association Between WO and TI, Respectively.

Note: Blue circles show the studies, and the size of the studies depicts their contribution to the overall effect size. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure, please refer to the web version of the article.)

Table 5. Explanation Provided by Moderators in Total Heterogeneity.

Moderator (Subgroup) Analysis of Sector of Employees

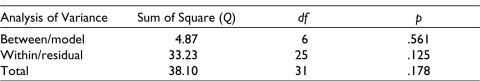

Since the moderator analysis did not have a substantial impact on the relationship between WO and TI, a subgroup analysis was conducted to investigate if there are variations in the effect of the intervention or exposure across different subgroups within the study population. The studies were categorized into five subgroups, denoted as follows: Group C for the corporate sector, E for the education sector, H for the healthcare sector, H1 for the hospitality sector, and O for the other sectors (see Table 6). The ANOVA results (Table 7) in our subgroup analysis revealed no significant differences among subgroups. Variations between subgroups were not statistically meaningful, as indicated by non-significant p values for both the “Between” (0.561) and “Within” (0.125) components. This suggests that differences between and within subgroups were not significantly different from what would be expected due to random chance. The overall variability in effect sizes across all subgroups was also not significantly different from random chance (p = .178). The pseudo R2 of 12.78% (Table 8) indicates that the moderator variables explain a moderate amount of variability in effect sizes. The high heterogeneity (I² = 93.07%) in our meta-analysis indicates the suitability of the random effects model over the fixed effects model. This model accounts for significant variability in effect sizes among studies, considering both within-study and between-study differences. In the context of WO and TI, the diverse effect sizes across studies suggest variations due to different samples and methods. The random effects model, by assuming a distribution of true effect sizes, provides a more realistic estimation, acknowledging inherent differences across studies compared to the fixed effects model, which assumes a single true effect size.

Table 6. Description of the Subgroups.

Table 7. Results of the Subgroup Analysis (ANOVA).

Table 8. Explained Variation.

Forest Plot for Subgroup Analysis of Sector of Employees

Forest plot in Figure 5 visually summarizes a subgroup analysis, illustrating the variation in the WO and TI relationship across different employment sectors. Each study is represented by a bar, with the midpoint indicating the estimated effect size and the bar’s length depicting the confidence interval. The overall effect size (0.28) is represented by a green dot, combining data from all studies, with its width indicating the confidence interval for the combined effect size.

Figure 5. Forest Plot for Subgroup Analysis of Sector of Employees.

Note: Group C: Corporate sector, E: Education sector, H: Healthcare sector, H1: Hospitality sector, and O: Other sectors.

Findings and Discussion

The meta-analysis of 32 studies involving 10,553 participants demonstrates a significant positive correlation (r = 0.31) between WO and TI. The obtained correlation of 0.31 falls within the range interpreted as a moderate effect according to Cohen’s benchmarks (Cohen, 1992). This highlights the increased likelihood of employees considering leaving their jobs when experiencing exclusion. The substantial heterogeneity (I² = 93.07%) suggests factors beyond the overall effect size contribute to variability in the WO–TI relationship across studies. Moderators examined were participants’ average age (8.08% impact) and the percentage of females (0.02%, no significant influence). Subgroup analysis across corporate, education, healthcare, hospitality, and other sectors did not reveal significant differences, with a pseudo R2 of 12.78% indicating a moderate degree of explanation of variability by sector. These findings underscore the consistent impact of WO on TI across different employment sectors. Despite varying settings and methodologies, this relationship remains robust, suggesting that the impact of WO on TI is a widespread phenomenon. For managers, this underscores the imperative to address WO as a key factor influencing employees’ intentions to leave. These findings recommend targeted interventions such as promoting inclusivity, conducting awareness training, and fostering positive interpersonal relationships. Acknowledging the broad impact of WO, managers can tailor practices to cultivate healthier work environments, enhancing employee retention and well-being.

Practical Implications

Our study has practical implications for managers and organizational leaders, highlighting the significance of addressing WO to reduce TI. Increased awareness of ostracizing behaviors can guide targeted interventions, including ostracism prevention training integrated into employee development initiatives. Strengthening human resource practices can enhance employee self-concept and foster positive relationships, mitigating the negative impacts of ostracism. Organizations should consider various factors such as demographics, personality traits, and leadership styles when designing strategies to combat workplace exclusion. Our study provides a roadmap for future research, outlining keywords, content boundaries, and unexplored gaps in the literature, encouraging scholars to explore nuanced aspects of WO. Practical recommendations emphasize fostering inclusive cultures, with managers promoting positive interactions and leadership training addressing supervisor ostracism. Proactively addressing WO contributes to healthier work environments, reducing TI, and enhancing overall organizational well-being. In essence, our study advocates for proactive measures, urging organizations to implement targeted interventions and prioritize inclusive cultures to create supportive workplaces.

Conclusion

In summary, our meta-analysis, based on 32 studies involving 10,553 participants from diverse sectors and locations, significantly advances our understanding of how WO relates to TI. The findings consistently reveal a noteworthy connection (correlation coefficient r = 0.31) between WO and employees’ intentions to leave their organizations. This underscores the pervasive and detrimental impact of ostracism across different work settings. While our study resolves inconsistencies in existing literature, we acknowledge limitations related to databases, timeframes, and language restrictions. Our practical recommendations for managers and stakeholders include fostering inclusive cultures, implementing prevention training, and strengthening interpersonal relationships to mitigate TI. Future research should explore additional dimensions of ostracism, diverse outcome variables, and factors influencing this relationship. Longitudinal designs and broader language inclusivity can further enrich the literature. Our study provides a foundation for ongoing exploration, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions to create healthier work environments and reduce the adverse effects of WO on employee turnover.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study on WO and TI has valuable insights but has limitations. We only utilized Scopus and WoS, potentially missing relevant literature from other databases like Google Scholar and ProQuest. Our study’s timeframe is limited to papers up to 2023, excluding post-2023 contributions. To capture the latest developments, future research should extend the timeline. We focused on English-language publications, potentially excluding valuable content in other languages. Future studies should adopt a more inclusive approach. While we examined the connection between WO and TI, TI represented just one aspect of withdrawal behavior. Future research should explore additional dimensions like absenteeism, lateness, cyberloafing, and so on, for a comprehensive understanding of how WO influences various aspects of employee disengagement. Further exploration of ostracism’s associations with various outcomes can provide a holistic view of its consequences. Investigating mediation and moderation factors, such as organizational cultures, can offer nuanced insights. Many included studies were cross-sectional, limiting our ability to establish causation. Future research using longitudinal designs can unravel temporal aspects.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Sudhir Chandra Das  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3511-8693

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3511-8693

Aktürk, C., & Ye ilta

ilta.png) , M. (2023). Seasonal employee leadership and turnover intention in the hospitality and tourism industry: Serial mediation model workplace ostracism and work alienation. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 41(1), 77–93.

, M. (2023). Seasonal employee leadership and turnover intention in the hospitality and tourism industry: Serial mediation model workplace ostracism and work alienation. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 41(1), 77–93.

Allen, K. A. (2020). The psychology of belonging. Routledge.

Anasori, E., Bayighomog, S. W., De Vita, G., & Altinay, L. (2021). The mediating role of psychological distress between ostracism, work engagement, and turnover intentions: An analysis in the Cypriot hospitality context. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102829.

Aplin-Houtz, M. J., Sanders, M., & Lane, E. K. (2023). A policy of potential problems: The buffering effects of the perceptions of pay secrecy and cynicism on workplace ostracism. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 35(4), 493–518.

Bashir, M., Zahra, S., Shah, S. H., Naeem, M. H., & Raza, S. (2024). Workplace ostracism and emotional exhaustion among private and public sector female bank employees. Journal of Health and Rehabilitation Research, 4(1), 109–115.

Baumeister, R. F., Wotman, S. R., & Stillwell, A. M. (1993). Unrequited love: On heartbreak, anger, guilt, scriptlessness, and humiliation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(3), 377. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.3.377

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Bothma, C. F., & Roodt, G. (2013). The validation of the turnover intention scale. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v11i1.507

Brewer, M. B., & Gardner, W. (1996). Who is this “We”? Levels of collective identity and self-representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(1), 83.

Brison, N., & Caesens, G. (2023). The Relationship between workplace ostracism and organizational dehumanization: The role of need to belong and its outcomes. Psychologica Belgica, 63(1), 120.

Choi, K. (2006). A structural relationship analysis of hotel employees’ turnover intention. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 11(4), 321–337.

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98–101.

Dysvik, A., & Kuvaas, B. (2010). Exploring the relative and combined influence of mastery-approach goals and work intrinsic motivation on employee turnover intention. Personnel Review, 39(5), 622–638.

Eagly, A. H. 1987. Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Erlbaum.

Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. 1999. The origins of sex differences in human behavior: Evolved dispositions versus social roles. American Psychologist, 54(6), 408–423.

Farasat, M., Afzal, U., Jabeen, S., Farhan, M., & Sattar, A. (2021). Impact of workplace ostracism on turnover intention: An empirical study from Pakistan. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(11), 265–276.

Ferris, D. L., Brown, D. J., Berry, J. W., & Lian, H. (2008). The development and validation of the workplace ostracism scale. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1348. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012743

Fiset, J., Al Hajj, R., & Vongas, J. G. (2017). Workplace ostracism seen through the lens of power. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1528.

Fox, S., & Stallworth, L. E. (2005). Racial/ethnic bullying: Exploring links between bullying and racism in the US workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(3), 438–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.01.002

Gou, L., Ma, S., Wang, G., Wen, X., & Zhang, Y. (2022). Relationship between workplace ostracism and turnover intention among nurses: The sequential mediating effects of emotional labor and nurse-patient relationship. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 27(7), 1596–1601.

Guyer, A. E., Caouette, J. D., Lee, C. C., & Ruiz, S. K. (2014). Will they like me? Adolescents’ emotional responses to peer evaluation. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38(2), 155–163.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Bowler, W. M. (2005). Organizational citizenship behaviors and burnout. Handbook of Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Review of Good Soldier Activity, 399–414.

Harvey, M., Moeller, M., Kiessling, T., & Dabicet, M. (2018). Ostracism in the workplace: Being voted off the island. Organizational Dynamics, 48(4), 100675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2018.08.006

Hitlan, R. T., Cliffton, R. J., & Desoto, M. C. (2006). Perceived exclusion in the workplace: The moderating effects of gender on work-related attitudes and psychological health. North American Journal of Psychology, 8, 217–236.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421.

Howard, M. C., Cogswell, J. E., & Smith, M. B. (2020). The antecedents and outcomes of workplace ostracism: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(6), 577.

Huyghebaert, T., Gillet, N., Audusseau, O., & Fouquereau, E. (2019). Perceived career opportunities, commitment to the supervisor, social isolation: Their effects on nurses’ well-being and turnover. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(1), 207–214.

Jones, E. E., Carter-Sowell, A. R., Kelly, J. R., & Williams, K. D. (2009). I’m out of the loop: Ostracism through information exclusion. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 12(2), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430208101054

Kim, H., & Stoner, M. (2008). Burnout and turnover intention among social workers: Effects of role stress, job autonomy and social support. Administration in Social work, 32(3), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/03643100801922357

Kim, S., & Ishikawa, J. (2021). Contrasting effects of “external” worker’s proactive behavior on their turnover intention: A moderated mediation model. Behavioral Sciences, 11(5), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11050070

Korman, B. A., Tröster, C., & Giessner, S. R. (2021). The consequences of incongruent abusive supervision: Anticipation of social exclusion, shame, and turnover intentions. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 28(3), 306–321.

Leung, A. S., Wu, L. Z., Chen, Y. Y., & Young, M. N. (2011). The impact of workplace ostracism in service organizations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(4), 836–844.

Lim, V. K. G., Chen, D., Aw, S. S. Y., & Tan, M. Z. (2016). Unemployed and exhausted? Job-search fatigue and reemployment quality. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.11.003

Liu, C., Li, H., & Li, L. (2022). Examining the curvilinear relationship of job performance, supervisor ostracism, and turnover intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 138, 103787.

Lockwood, N. R. (2006). Talent management: Driver for organizational success. SHRM Research Quarterly, 51(6), 1–11.

Lyu, Y., & Zhu, H. (2019). The predictive effects of workplace ostracism on employee attitudes: A job embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(4), 1083–1095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3741-x

Ma, Z., Song, L., & Huang, J. (2023). How maladjustment and workplace bullying affect newcomers’ turnover intentions: Roles of cognitive diversity and perceived inclusive practices. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(4), 1066–1086.

Mobley, W. H. (1977). Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(2), 237.

Mobley, W. H., Horner, S. O., & Hollingsworth, A. T. (1978). An evaluation of precursors of hospital employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63(4), 408. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.63.4.408

Mulki, J. P., & Jaramillo, F. (2011). Workplace isolation: Salespeople and supervisors in USA. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(04), 902–923.

O’Reilly, J., Robinson, S. L., Berdahl, J. L., & Banki, S. (2015). Is negative attention better than no attention? The comparative effects of ostracism and harassment at work. Organization Science, 26(3), 774–793.

Orhan, M. A., Rijsman, J. B., & Van Dijk, G. M. (2016). Invisible, therefore isolated: Comparative effects of team virtuality with task virtuality on workplace isolation and work outcomes. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 32(2), 109–122.

Ostracism: The power of silence. Guilford Press.

Ouyang, K., Lam, W., & Wang, W. (2015). Roles of gender and identification on abusive supervision and proactive behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32, 671–691.

Özkan, A. H. (2022). Abusive supervision climate and turnover intention: Is it my coworkers or my supervisor ostracizing me? Journal of Nursing Management, 30(6), 1462–1469.

Peng, Y., & Salter, N. P. (2021). Workplace ostracism among gender, age, and LGBTQ minorities, and people with disabilities. In C. Liu & J. Ma (Eds), Workplace ostracism: Its nature, antecedents, and consequences (pp. 233–267). Springer Nature.

Penhaligon, N. L., Louis, W. R., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2013). Feeling left out? The mediating role of perceived rejection on workgroup mistreatment and affective, behavioral, and organizational outcomes and the moderating role of organizational norms. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(3), 480–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2013.01026.x

Pharo, H., Gross, J., Richardson, R., & Hayne, H. (2011). Age-related changes in the effect of ostracism. Social Influence, 6(1), 22–38.

Price, J. (2001). Reflections on the determinants of voluntary turnover. International Journal of Manpower, 22, 600–624.

Prinstein, M. J., & Aikins, J. W. (2004). Cognitive moderators of the longitudinal association between peer rejection and adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JACP.0000019767.55592.63

Renn, R., Allen, D., & Huning, T. (2013). The relationship of social exclusion at work with self-defeating behavior and turnover. The Journal of Social Psychology, 153(2), 229–249.

Renn, R. W., Steinbauer, R., & Fenner, G. (2014). Employee behavioral activation and behavioral inhibition systems, manager ratings of employee job performance, and employee withdrawal. Human Performance, 27(4), 347–371.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698.

Robinson, S. L., O’Reilly, J., & Wang, W. (2013). Invisible at work: An integrated model of workplace ostracism. Journal of Management, 39(1), 203–231.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Enzmann, D. (1998). The burnout companion to study and research: A critical analysis. Taylor & Francis.

Scott, K. L., Zagenczyk, T. J., Schippers, M., Purvis, R. L., & Cruz, K. S. (2014). Co-worker exclusion and employee outcomes: An investigation of the moderating roles of perceived organizational and social support. Journal of Management Studies, 51(8), 1235–1256.

Sebastian, C., Viding, E., Williams, K. D., & Blakemore, S. J. (2010). Social brain development and the affective consequences of ostracism in adolescence. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 134–145.

Setyanto, S. H., & Hermawan, P. (2018). Analisa pengaruh stres kerja terhadap turnover intention karyawan hotel X surabaya. Jurnal Hospitality dan Manajemen Jasa, 6(2), 245–254.

Shapiro, K. L., Raymond, J. E., & Arnell, K. M. (1994). Attention to visual pattern information produces the attentional blink in rapid serial visual presentation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 20(2), 357.

Singh, L. B., & Srivastava, S. (2021). Linking workplace ostracism to turnover intention: A moderated mediation approach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 46, 244–256.

Soliman, M., Elbaz, A. M., Gulvady, S., Shabana, M. M., & Maher, H. (2023). An integrated model of the determinants and outcomes of workplace ostracism in the tourism industry. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 23(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584221093538

Srivastava, S., Pradhan, S., Singh, L. B., & Madan, P. (2022). Consequences of abusive supervision on Indian service sector professionals: A PLS-SEM-based approach. International Journal of Conflict Management, 33(4), 613–636.

Steel, R. P., & Ovalie, N. K. (1984). A review and meta-analysis of research on the relationship between behavioral intentions and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 673–686.

Tajfel, H. (1978). Social categorization, social identity and social comparison. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Differentiation Between Social Group (61–76). Academic Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology, 33(1), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.0066-4308/82/0201-0001502.00

Thoresen, C. J., Kaplan, S. A., Barsky, A. P., Warren, C. R., & de Chermont, K. (2003). The affective underpinnings of job perceptions and attitudes: A meta-analytic review and integration. Psychological Bulletin, 129(6), 914–945. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.914

Tikito, I., & Souissi, N. (2019). Meta-analysis of systematic literature review methods. International Journal of Modern Education and Computer Science, 12(2), 17.

Turkoglu, N., & Dalgic, A. (2019). The effect of ruminative thought style and workplace ostracism on turnover intention of hotel employees: The mediating effect of organizational identification. Tourism & Management Studies, 15(3), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2019.150302

Twenge, J. M., Catanese, K. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2002). Social exclusion causes self-defeating behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(3), 606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.3.606

Van Zelderen, A., Dries, N., & Marescaux, E. (2023). Talents under threat: The anticipation of being ostracized by non-talents drives talent turnover. Group & Organization Management. https://doi.org/10.1177/10596011231211639

Vui-Yee, K., & Yen-Hwa, T. (2020). When does ostracism lead to turnover intention? The moderated mediation model of job stress and job autonomy. IIMB Management Review, 32(3), 238–248.

Wang, Y., & Lai, P. (2023). When I see your pain: Effects of observing workplace ostracism on turnover intention and task performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 38(7), 527–540.

Wang, Z., Du, J., Yu, M., Meng, H., & Wu, J. (2021). Abusive supervision and newcomers’ turnover intention: A perceived workplace ostracism perspective. The Journal of General Psychology, 148(4), 398–413.

Williams, K. D. (2002). Ostracism: The power of silence. Guilford Press.

Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 425–452. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085641

Williams, K. D., & Gerber, J. (2004). Ostracism: The making of the ignored and excluded mind. Interaction Studies: Social Behaviour and Communication in Biological and Artificial Systems, 6(3), 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1075/is.6.3.04wil

Williams, K. D., & Sommer, K. L. (1997). Social ostracism by coworkers: Does rejection lead to loafing or compensation? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(7), 693–706.

Williams, K. D., Shore, W. J., & Grahe, J. E. (1998). The silent treatment: Perceptions of its behaviors and associated feelings. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 1(2), 117–141.

Yang, J. T. (2008). Effect of newcomer socialisation on organisational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intention in the hotel industry. The Service Industries Journal, 28(4), 429–443.

Yang, Y. J., & Lu, L. (2023). Influence mechanism and impacting boundary of workplace isolation on the employee’s negative behaviors. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1077739.

Zhang, L., Fan, C., Deng, Y., Lam, C. F., Hu, E., & Wang, L. (2019). Exploring the interpersonal determinants of job embeddedness and voluntary turnover: A conservation of resources perspective. Human Resource Management Journal, 29(3), 413–432.

Zhang, R., Niu, X., & Zhang, B. (2023). Workplace ostracism and turnover intention: A moderated mediation model of job insecurity and coaching leadership. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 41(1),109–122.

Zheng, X. M., Yang, J., Ngo, H. Y., Liu, X. Y., & Jiao, W. J. (2016). Workplace ostracism and its negative outcomes psychological capital as a moderator. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 15(4), 143–151.

Zhu, J., & Liu, W. (2020). A tale of two databases: The use of Web of Science and Scopus in academic papers. Scientometrics, 123(1), 321–335.

Zhu, Y., & Zhang, D. (2021). Workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behaviors: The chain mediating role of anger and turnover intention. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 761560.