1 Department of Higher Education, Government of Jammu and Kashmir, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India

2 Department of Commerce, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Notably, social-psychological approaches such as relative deprivation theory (personal and collective) and social exchange theory posit that there exists a negative association between women discrimination in HRM practices and organizational commitment. It is pertinent to note that the study of organizational commitment is significant across behavioral and attitudinal perspectives as well as differing conceptualizations. Considering this, the present study aims to investigate the causal linkages between women discrimination in HRM practices and the three-component model (TCM) of organizational commitment in the Indian banking sector. To test the hypothesized relationships, partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used on a sample of 394 women employees from the following banks in Northern India—State Bank of India, Punjab National Bank, Housing and Development Finance Corporation Bank, and Jammu and Kashmir Bank. The results obtained revealed that women discrimination in HRM practices has a significant negative impact on all three components of the TCM approach of organizational commitment—affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment. Specifically, the negative effect was found more on affective commitment and normative commitment, unlike continuance commitment. Consequently, the current study has thrown light on theoretical and managerial implications along with directions for future research.

Affective commitment, continuance commitment, Indian banking sector, normative commitment, organizational commitment, Women discrimination in HRM practices

Introduction

Undoubtedly, with the legal mechanism in place an overt that is, a blatant form of discrimination against women in HRM practices has become less frequent now (Dipboye & Colella, 2005; Richard et al., 2013). However, it has exacerbated subtle discrimination toward women. This is a subconscious and psychological process (Dworkin et al., 2018) to discriminate against them in employment contexts in a covert and complex form. Hence, is often difficult to identify and measure (Jones et al., 2017). Moreover, research highlights that discrimination against women in HRM practices whether overtly or covertly originates from gender stereotypes. These are prevalent in modern societies even today (Triana et al., 2021). These are the mental shortcuts of perceiving men and women differently based on their socially assumed roles and characteristics (Diekman & Eagly, 2000). For instance, women are supposed to have a feminine role. They are expected to possess communal traits such as kind, caring, emotional, friendly, and submissive. Contrarily, men are assumed to have a masculine role. Besides, they are assumed to possess agentic traits such as being competitive, achievement-oriented, confident, and energetic. These traits are believed to be considered necessary to perform well and achieve success across workplaces. However, research exhibits that there is a stereotypic belief prevailing among society that women usually lack these agentic traits (Eagly, 1987; Downes et al., 2014). This notion in turn spreads across the workplaces and manifests into discrimination of women in HRM practices overtly or subtly (Ackerman et al., 2005). This indicates that gender stereotypes lay a strong foundation for discrimination against women in HRM practices across workplaces. Although organizations worldwide have gender-neutral HRM policies and practices, research reveals that women employees are subjected to discrimination in HRM practices not necessarily in an overt form but covertly and subtly (Qu et al., 2019; Sunaryo et al., 2021). This is because the implementation of HRM practices toward women employees is not accompanied always with honesty and transparency. Rather sometimes, supervisors and managers who are generally found to be men (Ramya & Raghurama, 2016) and are usually concerned with the implementation of HRM practices possess a tendency to categorize women employees by gender regardless of legislation. This, in turn, may activate gender stereotypes among their subconscious minds which may prevent them from guiding their behavior (Ridgeway & England, 2007; Bobbitt-Zeher, 2011). As a result, their attitude toward women employees becomes discriminatory sometimes consciously or unconsciously (Elsawy & Elbadawe, 2022; Triana et al., 2021). Therefore, it would be appropriate to state that “women discrimination in HRM practices” is the product of a combination of cultural and social ideas about women. Also, the discretionary enforcement of HRM practices guided by gender stereotypic assumptions about women which hence translate into discriminatory outcomes toward them.

Furthermore, prior research has noted that workplace discrimination against women in HRM practices act as a crucial factor in determining various job attitudes and behaviors. These include job satisfaction, job involvement, employee performance, organizational citizenship behavior, turnover intention, organizational commitment, and employee engagement (Dost et al., 2012; Downes et al., 2014; Khan & Rainayee, 2020; Qu et al., 2019; Sattar & Nawaz, 2011; Sharma & Kaur, 2019). Among them, organizational commitment is the critical component of an employee attitude which is affected negatively when women employees experience discrimination in HRM practices (Downes et al., 2014; Munda, 2016; Khuong & Chi, 2017; Qu et al., 2019; Sunaryo et al., 2021; Triana et al., 2018). Notably, organizational commitment was being researched early in the 1950s as a single and multidimensional perspective (Suliman & Iles, 2000). However, few researchers considered it significant to study organizational commitment across multiple conceptualizations and dimensions (Meyer & Allen, 1991; O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986). The most influential of these efforts was the three-component model (TCM) developed by Meyer and Allen (1991). This reflects the three psychological states of an employee (Meyer et al., 1993) to continue their membership in a particular organization based on their desire (affective commitment), need (continuance commitment), and sense of responsibility (normative commitment). It is imperative to mention that, to date, extant literature has not investigated the impact of women discrimination in HRM practices on the TCM model of organizational commitment among the banking sector. This study is, therefore, an attempt to examine such linkages among Indian banks. The plausible reasons for choosing the banking sector are many: First, it is the most visible element of growth and plays a significant role in accelerating the economy of India (Gordon & Gupta, 2004). Second, if female employees working there experience any differential treatment in HRM practices, it can affect their organizational commitment (affective, continuance, and normative) negatively. This, in turn, may hamper the performance of banks and can create hurdles in the nation’s economic development. Third, there exists scant empirical research on banks in India examining discrimination against women in the majority of HRM practices (Bezbaruah, 2012; Ramya & Raghurama, 2016). Against this research backdrop, the present study intends to determine the relationship between women discrimination in HRM practices and the three-component model of organizational commitment in the banking sector of Northern India.

This study is imperative and will determine whether findings from previous research conducted across different nations and sectors on the phenomenon of “workplace discrimination against women” generalize to the Indian banking sector as well. Notably, banks in India represent a major player in the economy. As a result, they need a more committed workforce including women to face the worldwide economic competition effectively. The study will enable Indian banks to understand and address the perception of their women workforce regarding discrimination in HRM practices. Try to minimize and eliminate them so as to enhance their commitment in terms of desire (affective), need (continuance), and moral obligation (normative) toward their workplace. Furthermore, this study will enable banks across India to make adequate efforts. This involves not allowing gender stereotypes to influence the implementation of HRM practices toward women employees consciously or unconsciously.

Literature Review

Women Discrimination in HRM Practices

Over the past few decades, researchers all over the globe have shown increased research attention in management literature toward discrimination against women in the workplace (Goldman et al., 2006). Various scholarly definitions for “women discrimination in HRM practices” exist in the literature based on perceptions of events as discriminatory at the workplace (Phinney, 1992). For instance, Allport (1954) has defined “women discrimination in HRM practices” as the perception of women that they are denied equality of treatment at the workplace because of their gender. It is also defined as the perception of women employees that they are treated unfairly in employment decisions such as career advancement, challenging task assignments, compensation, performance appraisals, and training and development (Snizek & Neil, 1992). These decisions are based on their gender rather than merit, qualification, and performance (Gutek et al., 1996; Ngo et al., 2002). Additionally, few researchers have conceptualized “women discrimination in HRM practices” in terms of objective and structural barriers that indicate measurable events. In other words, the first-hand experience of women employees regarding disparities in organizational resources based on their gender has been used to operationalize the construct “women discrimination in HRM practices” (Phinney, 1992). Thus, based on such conceptualization various researchers have defined the construct in the following manner: Lenhart and Evans (1991) have defined it as a disparate treatment that women experience in personnel policies and practices based on their gender. According to Reskin and Padavic (1994), it simply means uneven dissemination of resources, possibilities, and incentives at the workplace on the premise of women’s gender. On the other hand, Cascio (1995) has defined “women discrimination in HRM practices” as an unjust or prejudicial treatment in employment activities such as hiring, pay, benefits, promotion opportunities, and performance evaluation of women belonging to a certain gender group. Besides, it depicts the experience of women employees that they are deprived of privileges and opportunities as available to their male counterparts at workplaces (Bobbitt-Zeher, 2011).

Broadly speaking, there exist two main contextual factors that contribute toward discrimination against women in HRM practices: (a) Gender stereotypes are generally, societal transcendentally held perceptions about feminism and masculinism based on gender roles and categories (Ben, 2008). For instance, the common stereotypes used to describe characteristics of males include-competitive, objective, decisive, rough, etc. While as, females are commonly described as compassionate, submissive, emotional, and so on (Rosen & Jerdee, 1974). Research highlights that employers, supervisors, and managers who are generally found to be men often carry stereotypic beliefs about women into the labor markets. They let such views function as a proxy for their current or future behavior as their individual-level screenings would necessitate large amounts of time and money (Browne & Kennelly, 1999; Sunaryo et al., 2021). This indicates that gendered assumptions about women and men which are the product of both history and culture permeate the walls of many employment settings. Thus, gender stereotypes lay the cultural foundation for discrimination (Elsawy & Elbadawe, 2022; Mwita & Mwakasangula, 2023) against women in HRM practices even today. (b) Career interruptions also emerge as one of the potential antecedents of discrimination against women in HRM practices. Research has noted that women experience career interruptions owing to their different life phases. These include marriage, motherhood, and additional family responsibilities (Ghiat & Zohra, 2023; Kingsley & Glynn, 1992). Subsequently, employers usually presume that career interruptions of women employees typically attach them only transiently to their workplace (Perlman & Pike, 1994). As a result, they deprive them of workplace opportunities available to men keeping into consideration the cost-benefit analysis (Estevez-Abe, 2005; Tlaiss & Dirani, 2015). Additionally, researchers have argued that when women undergo career interruptions owing to marriage, motherhood, and additional family responsibilities. This manifests into discrimination against them in HRM practices. This is because their employers hold a belief that they show a careless attitude toward their job and devote more time to their family commitments (Parray & Bhasin, 2013).

Existing literature has identified “women discrimination in HRM practices” as a multidimensional construct. This involves a broader spectrum of HRM practices such as career advancement, challenging task assignments, compensation, performance appraisal, and training and development.

Organizational Commitment

Organizational commitment has emerged as a promising area of research within the field of industrial/organizational psychology (Angel & Perry, 1981). It was being researched early in the 1950s as a single and multidimensional perspective (Suliman & Iles, 2000). According to Suliman and Iles (2000), the most single-dimensional approach to employee commitment is the attitudinal approach of Mowday et al. (1979). This views commitment as an employee’s attitude or a set of behavioral intentions. However, disagreements about the meaning of commitment and its implications for measurement persisted throughout the 1980s and 1990s. The investigators were often forced to choose among the varying alternatives. As a result, few researchers dealt with this complexity by treating commitment as a multidimensional construct (Meyer & Allen, 1991; O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986). The most influential of these efforts was the TCM model developed by Meyer and Allen (1991). This consolidates the behavioral and attitudinal perspectives as well as the differing conceptualizations of commitment. This approach is the most popular and very complex one in defining organizational commitment in terms of its three psychological states. This reflects the dominant themes inherent in the varying definitions of commitment—affective, continuance, and normative (Meyer & Allen, 1991).

Women Discrimination in HRM Practices and Organizational Commitment

A plethora of research has revealed that organizations worldwide are facing challenges in sustaining commitment among their women workforce. This is because they are mostly subjected to discrimination within an organizational context (Downes et al., 2014; Foley et al., 2006; Khuong & Chi, 2017; Munda, 2016; Welle & Heilman, 2005). Notably, there is a need for organizations to have committed women workforce in contemporary times to achieve effective performance and success. As a result, this study is an attempt to examine women discrimination in HRM practices in relationship to organizational commitment among Indian banks. Research has noted that gender stereotypes and career interruptions owing to marriage, motherhood, and associated family responsibilities are the potent causes of workplace discrimination against women in HRM practices (Elsawy & Elbadawe, 2022; Ghiat & Zohra, 2023). Besides, existing literature has identified that the two social-psychological approaches such as relative deprivation theory (personal and collective) and social exchange theory better explain the intersection between women discrimination in HRM practices and organizational commitment (Branscombe & Ellemers, 1998; Ensher et al., 2001; King & Cortina, 2010). More precisely, the relative deprivation theory states that when women employees perceive they have been discriminated against at the workplace or their group (female) to which they belong has been in a disadvantaged position (Crosby, 1982; Gutek et al., 1996). This generates a feeling of deprivation among them based on their own experience (personal relative deprivation) or the experience of their in-group members (collective relative deprivation). Consequently, their organizational commitment is affected negatively. Besides, social exchange theory also explains the negative association between women discrimination in HRM practices and organizational commitment. This theory illustrates that when women employees perceive discrimination in HRM practices. It manifests into a negative exchange between them and their organization. Hence, they reciprocate by exhibiting low organizational commitment (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002; Turnley et al., 2003). It is pertinent to note that examining such causal linkages will be beneficial for selected banks. For instance, it will enable them to keep track of differential treatment if any exists against women employees whether overtly or covertly. Try to minimize and prevent it from occurring in order to maintain an organizational commitment among them.

Additionally, there is theoretical support regarding the importance of studying organizational commitment from multiple perspectives and conceptualizations (Meyer & Allen, 1991). Subsequently, it would be appropriate to examine the impact of women discrimination in HRM practices on the TCM model of organizational commitment (affective, continuance, and normative) in this study. Against this backdrop, a review of the literature was done to identify such casual linkages. For instance, Korabik and Rosin (1991) have investigated workplace variables in relationship with affective commitment. Their findings revealed that when women employees felt that their expectations had not been met, described their jobs as limited in leadership, responsibility, and being worked in a male-dominated environment. Their affective commitment toward their workplace was found to be low. Shaffer et al. (2000) have shown in their study that women employees working across the United States of America, the Chinese mainland, and Hong Kong continued to encounter discrimination in hiring, pay raises, career progression, and performance appraisal. This in turn has a negative impact on their affective commitment and normative commitment. Moreover, research has revealed that women employees perceived a higher level of gender discrimination than men in hiring, pay raises, performance evaluation, and career advancement (Foley et al., 2006). Besides, the findings suggested that women more strongly attributed gender discrimination to their organization than men. This is because for them discrimination is more about intergroup comparison. While as, for men, it is about intragroup comparison (Schmitt et al., 2002). As a result, women employees’ affective commitment toward their organization is reduced more significantly than men. Triana et al. (2018) have examined 85 studies and found consistent empirical evidence for the link between workplace discrimination against women in HRM practices and affective commitment across multiple countries—the US, Hong Kong, China, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Belgium, and Australia. Several studies have also shown that women employees encounter organizational barriers that make them feel deprived. Consequently, they reciprocate by exhibiting low affective commitment toward their workplace (Eghlidi & Karimi, 2020; Qu et al., 2019; Sunaryo et al., 2021). In light of the above discussion, it is pertinent to mention that previous research has put much emphasis on examining the links between women discrimination in HRM practices and affective commitment. Notably, the existing literature has highlighted an absolute dearth of studies on assessing the impact of women discrimination in HRM practices on the TCM model of organizational commitment. Olori and Comfort (2017) have only investigated such a relationship revealing a significant negative impact of women discrimination in HRM practices on three dimensions of the TCM approach (affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment). Given such a theoretical gap the present study seeks to estimate the said linkages in the Indian banking sector. It seeks to arrive at the answers to the following key questions:

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework.

Source: Literature review.

RQ1: To what extent do women discrimination in HRM practices influence an affective commitment among Indian banks?

RQ2: To what extent do women discrimination in HRM practices impact a continuance commitment across banks in India?

RQ3: To what extent do women discrimination in HRM practices affect a normative commitment across Indian banks?

Research Hypotheses

The following research hypotheses are formulated to test them among banks across Northern India to contribute to the existing body of knowledge.

H1:Women discrimination in HRM practices has a significant negative impact on affective commitment.

H2: Women discrimination in HRM practices has a significant negative influence on continuance commitment.

H3: Women discrimination in HRM practices has a significant negative effect on normative commitment.

Research Methodology

Research Instrument

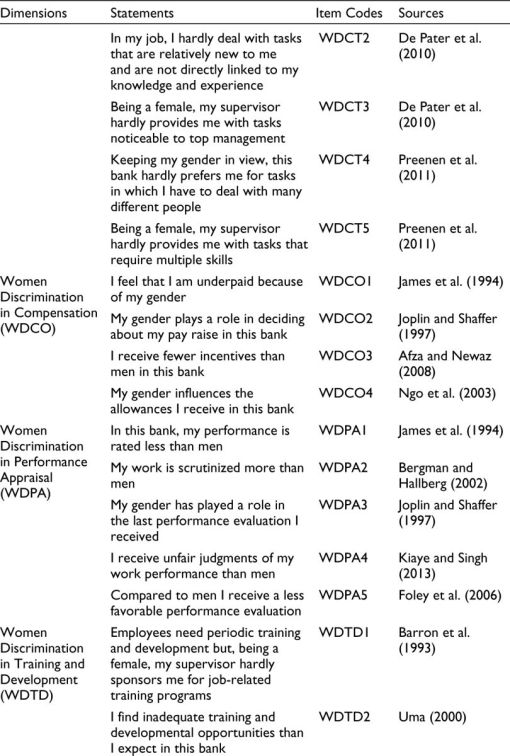

As discussed in the preceding sections, the construct “women discrimination in HRM practices” in this study covers a wider spectrum of HRM practices such as career advancement, challenging task assignments, compensation, performance appraisal, and training and development. It is imperative to mention that there exists no single survey instrument in the literature that could have measured the underlying construct according to its conceptualization and domain in the present study. Subsequently, as posited by the literature, a standardized survey instrument was designed to measure the construct across its dimensions by devising an item pool from the various scales (Churchill Jr, 1979; Lankford & Howard, 1994). The details about the generation of 25 scale items relating to the aforementioned dimensions are illustrated in Table A1 (see Appendix A). Besides, items were graded on a five-point Likert scale ranging from one for strongly disagree to five for strongly agree. The participants’ responses to the items in women discrimination in HRM practices were elicited.

To measure the TCM approach to organizational commitment, the revised scale of Meyer et al. (1993) was adopted. It is widely applicable in the field of organizational behavior research across the globe. This instrument is also significant in terms of covering broader conceptualizations of organizational commitment—attitudinal and behavioral. It consists of 18 items given in Table A2 (see Appendix A). Besides, all these items were measured on a five-point scale.

Sampling Design and Database

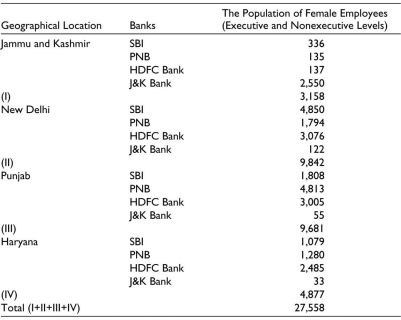

The accessible population of this study was limited to female bank employees working at executive and nonexecutive levels. The selected banks included–State Bank of India (SBI), Punjab National Bank (PNB), Housing and Development Finance Corporation (HDFC) Bank, and Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) Bank. The survey was conducted in these geographical locations of Northern India—Jammu and Kashmir, New Delhi, Punjab, and Haryana. For the survey, a nonprobability convenience sampling technique was used considering the hectic work schedule of women bankers. An accessible population in this study is contained in Table 1. Existing research suggests several ways to determine sample sizes such as sample-to-variable ratio, general rules-of-thumb, and many more. For instance, most researchers believe that a sample size of 200–500 people is enough (Chen et al., 2019). While, others suggest a minimum observation-to-variable ratio of 5:1, 15:1, or 20:1 (Hair Jr et al., 2010). Similarly, Yamane (1967) model provides a simplified formula for calculating the sample size when the population is finite and known. This is a simple and easiest way to arrive at a more reliable sample size and is widely applicable in social science research. .png) , where n is the sample size, N is the population size (accessible population), and e is the level of precision (5% often recommended for social science research).

, where n is the sample size, N is the population size (accessible population), and e is the level of precision (5% often recommended for social science research).

Table 1. Accessible Population of the Study.

Source: (1). SBI, Regional HRD Office, Maulana Azad Road, Srinagar, J&K. (2). PNB, Area Office, Batwara, Srinagar, J&K. (3). HDFC Bank, HRD Section, Residency Road, Srinagar, J&K. (4). J&K Bank Corporate Headquarters, Maulana Azad Road, Srinagar, J&K.

Therefore, in light of the above discussion the current study has considered Yamane (1967) model as the most appropriate approach for computing an adequate sample size because of two main reasons: First, it uses a simplified formula to get a reliable sample size. Second, an accessible population of the study is known and finite, that is, N = 27,558. Thus, the required sample size (n) obtained for this study through this approach is 394. This also fits the criteria as recommended by researchers such as Chen et al. (2019) and Hair Jr et al. (2010). Besides, 25% has been added to it to compensate for nonresponse bias and ineffective responses (Hair Jr et al., 2010; Israel, 2003). This makes an approachable sample size of 493 (394+99). A total of 493 questionnaires were distributed, with 434 being returned (88% response rate). All responses with missing data (37) were also eliminated, leaving 397 responses eligible for subsequent analysis. The data was collected during the period from July 2022 to November 2022.

Analysis and Interpretation

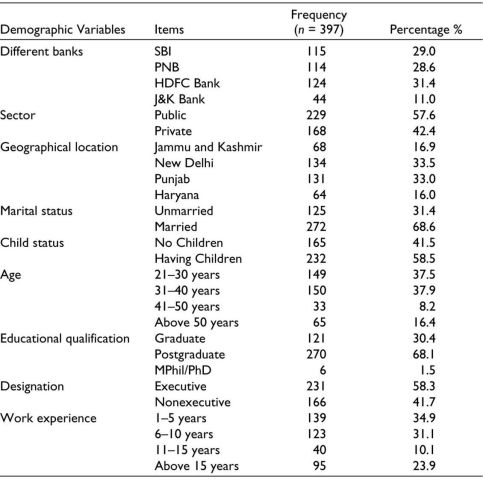

Table 2 contains the demographic profile of the sample respondents. The majority of female bankers are from HDFC Bank (31.4%) followed by SBI (29%) and PNB (28.6%). However, a minimum number of respondents are from J&K Bank (11%). Furthermore, the majority (57.6%) of sample respondents are from public sector banks. While as 42.4% are from private sector banks. It is also observed that the majority of female bankers are from New Delhi (33.5%) and Punjab (33%). However, there are only 16.9% of female bankers from Jammu and Kashmir and 16% are from Haryana. As far as marital and child status is concerned, 68.6% of sample participants are married and 31.4% are unmarried. Contrarily, 58.5% of sample respondents have children and 41.5% do not have children. In addition, the majority of sample respondents are within the age groups of 21–30 years (37.5%) and 31–40 years (37.9%). While 16.4% are from the above 50 years of age group and only 8.2% are from the 41–50 years of age group. Moreover, the maximum number of respondents in this study are postgraduates (68.1%) and 30.4% are graduates. However, a small percentage has MPhil/PhD degrees (1.5%). Besides, the majority of sample participants are executives (58.3%) while nonexecutives are only 41.7%. Lastly, the maximum number of female bankers has work experience of 1–5 years (34.9%) and 6–10 years (31.1%). However, 23.9% have more than 15 years of work experience and only 10.1% have 11–15 years of work experience.

Table 2. Demographic Profile of Sample Respondents.

Source: Primary data.

Measurement Model Assessment (Lower-Order)

This study chooses PLS-SEM to examine the reliability and validity—convergent and discriminant for the constructs of this study. Notably, the construct—women discrimination in HRM practices involved in this study is higher-order in nature (Bollen & Diamantopoulos, 2017; Hair Jr et al., 2014). This consists of five lower-order constructs (dimensions)—women discrimination in career advancement, women discrimination in challenging task assignments, women discrimination in compensation, women discrimination in performance appraisal, and women discrimination in training and development. According to Sarstedt et al. (2019), the measurement model in this study was assessed first at the lower-order level. This includes these five dimensions of women discrimination in HRM practices and three components of organizational commitment—affective, continuance, and normative. In the first instance, the reliability of these lower-order constructs was examined using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (rho_c) with a threshold limit of 0.6 or 0.7 (Hair Jr et al., 2014). Table 3 displayed that Cronbach’s alpha values (a conservative measure of reliability) for these five dimensions of women discrimination in HRM practices (mentioned above) were 0.922, 0.908, 0.789, 0.905, and 0.904. In addition, Cronbach’s alpha values for affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment were found to be 0.887, 0.859, and 0.861 (see Table 3). Moreover, the composite reliability which is an appropriate measure for internal consistency in SEM was calculated. It offers a more retrospective approach to overall reliability. It estimates the consistency of the construct itself including the stability and equivalence of the construct (Hair Jr et al., 2010). Table 3 showed that composite reliability values for these five lower-order constructs of women discrimination in HRM practices were 0.939, 0.931, 0.862, 0.930, and 0.929. For affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment, the CR values found were 0.913, 0.891, and 0.895 (see Table 5). The values of Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability for all lower-order constructs in the measurement model were above 0.70. This indicates a satisfactory to good reliability (Hair Jr et al., 2014).

Table 3. Reliability and Average Variance Extracted.

Source: Smart PLS output.

After examining the reliability, the convergent validity was estimated through two commonly used measures—factor loadings of indicators and average variance extracted (AVE) with the minimum 0.5 thresholds (Hair Jr et al., 2014). Table A3 (see Appendix A) revealed that factor loadings of indicators of all lower-order constructs of this study were greater than 0.50 on an associated construct that they intend to measure. Besides, AVE values for all lower-order constructs were also greater than 0.50 (see Table 3). The result of both these measures (factor loadings and AVE) indicated that there exists a good convergent validity in all lower-order constructs. Furthermore, to examine their discriminant validity, the two popular measures were used—Fornell–Larcker criterion, and Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT). The Fornell and Larcker Criterion shall depict that the square root of the AVE of each latent construct shall be greater than the correlations of the latent constructs. For the HTMT ratio, all correlations should be below 0.85. Table 4 revealed that the square root of AVE of each lower-order construct (represented by bold, italic, and diagonal values) was greater than its highest correlations with other constructs (off-diagonal values). The HTMT ratio value for all lower-order constructs was also within the threshold limit of 0.85. Hence, depicting their discriminant validity.

Table 4. Discriminant Validity of Lower-Order Constructs.

Source: Smart PLS output.

Measurement Model Assessment (Higher-Order)

This study involves women discrimination in HRM practices as a higher-order construct. The reliability and validity of its lower-order constructs (dimensions) were estimated in the previous section. The next step is to examine its reliability and validity at a higher-order level. This was done using a dis-joint two-stage approach (Sarstedt et al., 2019). First, the reliability of women discrimination in HRM practices at higher-order levels was examined through Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability. Table 5 showed their values as 0.842 and 0.888 which testifies that the respective construct has an acceptable internal consistency of data.

Table 5. Reliability and Convergent Validity.

Source: Smart PLS output.

Additionally, Table 5 showed the values of AVE and factor loadings were well above the 0.5 threshold limit (Hair Jr et al., 2015). The factor loadings ranged from 0.657 to 0.837 for women discrimination in HRM practices. This indicates a well-established convergent validity. Similarly, to examine the discriminant validity, Fornell and Larcker Criterion showed that the square root of AVE for women discrimination in HRM practices, (0.785), affective commitment (0.798), continuance commitment (0.750), and normative commitment (0.767) were well above the correlation between the constructs (see Table 6). For HTMT ratio, all correlations found were below 0.85. From this, we concluded that all these constructs possess discriminant validity.

Table 6. Discriminant Validity of Higher-Order Constructs.

Source: Smart PLS output.

Testing of Research Hypotheses: Results

To test the hypotheses of this study, a partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) tool was used. The analysis was performed in smart PLS version 3.3.9 statistical software. It involves an assessment of the structural model to examine the research hypotheses of the present research (Hair Jr et al., 2010). There are various standard assessment criteria that need to be considered in a structural model—the relevance of path coefficients, and their statistical significance (bootstrapping), coefficient of determination (R2), f2 (effect size), and the blindfolding-based cross-validated redundancy measure Q2 (Hair Jr et al., 2010). A complete bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 subsamples was used to examine the impact of women discrimination in HRM practices on affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment. Table 7 and Figure 2 contain the results of the structural model. The estimates obtained reveal that empirical values of t were greater than its critical value at 5% level of significance for each path (β = .png) 0.527, t =14.863; β =

0.527, t =14.863; β = .png) 0.157, t = 2.771; β =

0.157, t = 2.771; β = .png) 0.447, t = 11.310; p < 0.05). Hence, indicating the significant negative impact of women discrimination in HRM practices on affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment. The findings lend support to all three hypotheses of this study (H1, H2, and H3). The result of hypothesis (H1) is in line with Shaffer et al. (2000), Foley et al. (2005), Foley et al. (2006), Downes et al. (2014), and Qu et al. (2019). Further, the result of hypothesis (H2) aligns with Olori and Comfort (2017). While as the result of hypothesis (H3) is in line with Shaffer et al. (2000) and Olori and Comfort (2017). More precisely, it was found that women discrimination in HRM practices has a stronger negative impact on affective commitment (β =

0.447, t = 11.310; p < 0.05). Hence, indicating the significant negative impact of women discrimination in HRM practices on affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment. The findings lend support to all three hypotheses of this study (H1, H2, and H3). The result of hypothesis (H1) is in line with Shaffer et al. (2000), Foley et al. (2005), Foley et al. (2006), Downes et al. (2014), and Qu et al. (2019). Further, the result of hypothesis (H2) aligns with Olori and Comfort (2017). While as the result of hypothesis (H3) is in line with Shaffer et al. (2000) and Olori and Comfort (2017). More precisely, it was found that women discrimination in HRM practices has a stronger negative impact on affective commitment (β = .png) 0.527) and normative commitment (β =

0.527) and normative commitment (β = .png) 0.447) unlike continuance commitment (β =

0.447) unlike continuance commitment (β = .png) 0.157). Besides, the effect size (f²) values for affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment were found to be 0.384, 0.025, and 0.250 (see Table 7). Hence, indicating the large, small, and medium-to-large effect sizes (Cohen, 1988). Notably, these (f²) values revealed that there would be a substantial impact on affective commitment and normative commitment if women discrimination in HRM practices (an exogenous construct) is to be omitted from the model. However, the least impact would be on continuance commitment. These (f²) values have contributed to the research by revealing the immense role women discrimination in HRM practices have in this study for explaining affective commitment and normative commitment. This underlying exogenous construct decreases these two commitment forms of women employees more strongly than their continuance commitment.

0.157). Besides, the effect size (f²) values for affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment were found to be 0.384, 0.025, and 0.250 (see Table 7). Hence, indicating the large, small, and medium-to-large effect sizes (Cohen, 1988). Notably, these (f²) values revealed that there would be a substantial impact on affective commitment and normative commitment if women discrimination in HRM practices (an exogenous construct) is to be omitted from the model. However, the least impact would be on continuance commitment. These (f²) values have contributed to the research by revealing the immense role women discrimination in HRM practices have in this study for explaining affective commitment and normative commitment. This underlying exogenous construct decreases these two commitment forms of women employees more strongly than their continuance commitment.

Table 7. Hypotheses Testing Results.

Source: Smart PLS output.

Note: WDHRMP = Women Discrimination in HRM Practices, AC = Affective Commitment, CC = Continuance Commitment, NC = Normative Commitment. * = p < .05, significant at a 95% confidence level.

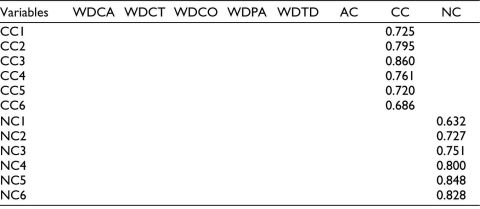

Figure 2. Structural Model.

Source: Smart PLS output. Nonbootstrapped Research Model specifying the relationship of Women Discrimination in HRM Practices with Affective commitment, Continuance commitment, and normative commitment.

Note: WDCA, WDCO, WDCT, WDPA, and WDTD = manifest variables of Women Discrimination in HRM Practices.

In addition, the coefficient of determination (R2) which depicts the explanatory power of the model was found to be 0.278, 0.025, and 0.200 for affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment (see Table 7 and Figure 2). Such values of (R2) for affective commitment and normative commitment are considered quite satisfactory and acceptable in behavioral science research (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017). However, for continuance commitment (R2) value is found to be very weak. These results indicated that women discrimination in HRM practices has a significant role in explaining the decrease in affective commitment and normative commitment. Contrarily, it has a minimum role in reducing the continuance commitment of female bankers. These findings are consistent with previous studies like Gutek et al. (1996), Shaffer et al. (2000), Downes et al. (2014), Olori and Comfort (2017), and Qu et al. (2019). The research findings of this study have relevance for future researchers. For instance, they can cross-validate the results of the present research in different workplace contexts in future. They can empirically prove that if women workforce will experience any differential treatment in HRM practices. This will reduce their emotional attachment to the workplace more significantly (affective commitment). Besides, their moral obligation toward their employer (normative commitment) will also decrease substantially. Contrarily, their continuance commitment will remain least affected. The plausible cause could be the future job market scenario in India that will be characterized by maximum job cuts owing to artificial intelligence. Consequently, even if women employees will experience any discrimination at the workplace, they will be likely to continue their jobs. This is because there will be scarce job opportunities in future. Notably, these (R2) values do not imply the predictive power. As a result, in order to finalize an estimated model and generalize the findings of the study, (Q2) is computed (Hair Jr et al., 2014). Stone-Geisser’s cross-validated redundancy measure (Q2) for this study arrived at greater than zero (see Table 7) for affective commitment (0.168), continuance commitment (0.006), and normative commitment (0.110). This showed that the model has a good predictive relevance (Sarstedt et al., 2014a). In other words, these values of (Q2) indicated a higher level of generalizability for the conclusions of this study. Thus, revealing that the model is highly generalized and possesses external validity.

Additionally, the results of this study contribute to the broader research theme in the following manner: Undoubtedly, the differential treatment toward women in HRM practices appears to be nuanced in modern times. Yet, it possesses the tendency to affect their organizational commitment negatively—affective, continuance, and normative as found in this research. Furthermore, the research findings have confirmed the two socio-psychological approaches, namely—relative deprivation theory and social exchange theory (Blau, 1964; Crosby, 1982; Gutek et al., 1996; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). These theories suggest that when women employees experience discrimination in HRM practices at their workplace. This in turn signals to them that they are not valued by their organization. As a result, based on norms of reciprocity they exhibit low organizational commitment in terms of desire, need, and obligation. Moreover, the findings of this research have implications for understudied banks as well—SBI, PNB, HDFC Bank, and J&K Bank. They are suggested that they should not take the feeling of differential treatment among their women workforce regarding HRM practices for granted. Rather they must manage their perceptions carefully considering the undesirable consequences on their affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment.

Discussions and Conclusions

Although, in contemporary times women employees are not subjected to overt discrimination in HRM practices. However, it does not indicate that discrimination against them does not exist at all. Notably, the differential treatment toward them appears to be nuanced and subtle. Besides, it possesses the tendency to affect their job-related attitudes and behaviors across workplaces negatively (Jones et al., 2017; Sunaryo et al., 2021; Triana et al., 2021). Against this research backdrop, the results of this study exhibited that women discrimination in HRM practices has a significant negative impact on affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment across banks. Specifically, the negative effect is found more on affective commitment and normative commitment, unlike continuance commitment. These findings are consistent with previous studies revealing that perception of discrimination in HRM practices has a strong role in decreasing an affective commitment and normative commitment of women employees (Downes et al., 2014; Olori & Comfort, 2017; Qu et al., 2019; Shaffer et al., 2000). However, it has a minimum role in reducing their continuance commitment (Gutek et al., 1996; Olori & Comfort, 2017). The plausible explanation could be that women by nature are emotional, empathetic, and friendly. They get easily attached to their workplace and possess an intense emotional bond toward it. Consequently, they also show a strong sense of obligation to remain committed to their organization. Therefore, when women bankers in this study perceived a differential treatment toward themselves in HRM practices it had a more negative impact on their affective commitment and normative commitment. These findings also align with relative deprivation theory and social exchange theory (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002; Turnley et al., 2003) asserting that when women employees see their workplace as biased toward them whether overtly or subtly. It generates a feeling of deprivation among them and affects the nature of the exchange relationship with their organization negatively. Subsequently, they exhibit less affective commitment and normative commitment toward their workplace.

Contrarily, the findings of this study indicated that the perception of women bankers regarding differential treatment in HRM practices had a less negative impact on their continuance commitment. This could be possibly owing to various reasons: First, women bankers might be aware of the prevailing job market in India where fewer suitable and alternative job opportunities exist (Gutek et al., 1996; Olori & Comfort, 2017). Consequently, even if they experience discrimination in HRM practices at banks, they continue with their existing job. Second, they are acquainted with the fact that gender stereotypic belief is deeply embedded in the subconscious minds of supervisors who are generally found to be men at every organization (Ramya & Raghurama, 2016). As a result, they hold a belief that their competence and capability will be judged negatively at every workplace. That is why even if they perceived discrimination in HRM practices across banks they considered it futile to change their existing job. Lastly, they might be aware of the financial costs associated with leaving the job. As a result, their continuance commitment gets least affected even if they perceived discrimination in HRM practices. Considering, the research findings of this study, it can be concluded that discrimination against women bankers still exists though not in an overt form but in a covert manner. Besides, it triggers a negative outlook among them by having an unfavorable impact on their affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment.

Additionally, the research findings of this study have several theoretical implications. For instance, there exist sparse studies examining the association between women discrimination in HRM practices and the TCM model of organizational commitment (Olori & Comfort, 2017). Therefore, the present research contributes to the existing body of knowledge by assessing such direct causal linkages among Indian banks. It has also contributed to the existing literature by exhibiting a more negative impact on affective commitment and normative commitment of women bankers compared to their continuance commitment. Moreover, the results of the study imply the understudied banks to recognize the importance of gender diversity programs. These must be organized to change the gender stereotypic belief of their managers who are generally found to be men about the women workforce. This in turn will reduce the inequalities of women in HRM practices and create a positive work environment for them. Consequently, their commitment to their employer banks will enhance in terms of emotions, wants, and moral obligations. Furthermore, it is suggested that research studies in the future be conducted to continue examining the nuances of discrimination against women in HRM practices. These should go beyond traditionally studied contexts and conceptualizations to include more subtle forms of discrimination against women (Triana et al., 2021). Therefore, in light of the above discussion, we can conclude that having a gender-inclusive HRM practice in place is not sufficient to achieve equality for women employees. Rather Indian banks must ensure that HRM practices toward them are implemented fairly. For that, they must train the supervisors and managers regularly to remain conscious of their preconceived beliefs about women. Not allow them to affect the personnel decisions relating to women workforce. This in turn results in congruence between a gender-inclusive culture and the informal power process across Indian banks. To conclude, we can say that complete equality of women across banks is imperative. Without it, the global economies are in danger and hence will collapse. The sooner we realize this fact, the better it would be and the time to act is now.

Theoretical Implications

The current research has contributed to the existing literature in several ways. First, it has enriched an existing knowledge base by concurring with the relative deprivation theory—personal and collective (Crosby, 1982; Gutek et al., 1996). Hence, claiming the significant negative relationship between women discrimination in HRM practices and TCM approach of organizational commitment. In other words, the study revealed that when women bankers perceived that they or their in-group members to which they belonged (female) received differential treatment at the workplace compared to men. This generated a feeling of deprivation among them at a personal level (personal deprivation) or they feel deprived on behalf of their in-group members (collective deprivation). As a result, their affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment toward their workplace got affected negatively. Second, this study has contributed to the existing literature by lending support to social exchange theory (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002; Turnley et al., 2003). In other words, the current research has proven that when women bankers experienced differential treatment in HRM practices. It affected their nature of exchange relationships with their employer banks negatively. Subsequently, they reciprocated by exhibiting low commitment (affective, continuance and normative) toward their workplace. Thirdly, there exists the sparse studies examining the impact of women discrimination in HRM practices on the TCM model of organizational commitment (Olori & Comfort, 2017). Considering this, the study has enhanced the existing body of knowledge by assessing such direct causal linkages. Besides, it has contributed to the existing literature by exhibiting a varied negative impact of women discrimination in HRM practices on the TCM approach of organizational commitment. This negative impact was found more on affective commitment and normative commitment of women bankers compared to their continuance commitment. Fourth, the present study has enriched the existing literature by using an expanded research framework to examine the full spectrum of women employees’ perceptions regarding discrimination in HRM practices. Notably, the prior research has failed to make such a broader assessment of women discrimination in HRM practices such as career advancement, compensation, challenging task assignments, performance appraisal, and training and development (Qu et al., 2019; Sunaryo et al., 2021; Triana et al., 2021). Fifth, the present research has contributed to the body of knowledge by devising an appropriate instrument for measuring the construct “women discrimination in HRM practices” as per its conceptualization and domain in the study. This involved generating an item pool from various standardized scales as well as from existing literature. A reliable and valid instrument was found through measurement model assessment. Thus, enhancing the existing literature both theoretically and empirically.

Managerial Implications

On account of the research findings of this study women discrimination in HRM practices has a more negative impact on affective commitment and normative commitment of women bankers. While as, there existed less negative impact on their continuance commitment. This study offers several practical implications for understudied banks—SBI, PNB, HDFC Bank, and J&K Bank. First, to gain a better understanding about how their women workforce develops such discriminatory perceptions in HRM practices. These banks are implied to take the services of counselors and psychologists in order to handle and reduce their perceptions. This will in turn enhance their affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment toward their workplace. Thus, improving the performance and functioning of these banks. Second, it is suggested that the selected banks adopt an objective approach and make a more accurate assessment of the abilities and competence of their women workforce. Rather than basing personnel decisions relating to them on mere gendered assumptions. Third, the HR practitioners in these banks are recommended to play an instrumental role in managing and reducing such biased perceptions of women employees. For that, they can make consistent use of assessment tools such as opinion surveys, focus groups, an analysis of patterns of women employees’ grievances, and an effective support system. This in turn will enhance their commitment to their workplace in terms of desire (affective), need (continuance), and moral obligation (normative). Subsequently, these banks will achieve effective organizational performance and success. Fourth, to face the worldwide economic competition effectively these banks are implied to keep the track of inequities toward their women employees in HRM practices. Their top-level management, HRD professionals, and branch heads must recognize the adage that “perception is 99 % of reality.” As a result, they should understand why and how their women employees have developed such discriminatory perceptions in HRM practices. What are its root causes? Although, it is harder from an organizational standpoint to control the modern form of discrimination against women in HRM practices. This is because it appears to be complex and nuanced. Besides, it has its roots deeply embedded in gender stereotypes. Therefore, timely intervention is paramount to target this notion prevailing in the subconscious minds of branch heads, HR managers who are generally found to be men. They must be trained so that their gender stereotypic notion do not creep into the implementation of HRM practices toward women employees consciously or unconsciously. They should ensure that the HRM practices are enforced with honesty given the competence and merit of the women workforce rather than their gender. This in turn will help in minimizing and eliminating such discriminatory perceptions among women employees. Subsequently, their organizational commitment in terms of emotions (affective), need (continuance), and moral obligation (normative) toward their workplace will enhance.

Additionally, the study has several implications for the banking sector in India as well. For instance, there exist special cells, an online grievance redressal system, and internal complaint committees in most Indian banks to deal with discrimination against women at workplace. However, there is a need for a robust mechanism across all banks in India to handle the modern form of discrimination against women in HRM practices. This is because such bias appears to be covert and obscure and is difficult to identify and measure. Furthermore, the Government of India is also suggested to play a proactive role in eradicating discrimination against women in HRM practices across Indian banks. Notably, the Indian constitution puts a thrust on the “concept of egalitarianism.” Yet, there is still a long way to go as discrimination against women in HRM practices is still persistent across Indian banks though not overtly but subtly. This indicates that the current legal machinery in India is not that stringent to deal with a covert and invisible form of discrimination against women in HRM practices. Consequently, the Indian government is recommended to revisit the existing laws and reframe them. This can reduce a modern form of discrimination against women in HRM practices to the fullest.

Future Research

The current study revealed that women workforce across the understudied banks in Northern India—SBI, PNB, HDFC Bank, and J&K Bank are subjected to discrimination in HRM practices. This in turn had a significant negative effect on their affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment. The study has contributed to the existing literature both theoretically and empirically. However, the survey methodology used has not measured the frequency of acts of discrimination against women bankers in the workplace. To get a more accurate picture, subsequent research should measure the frequency of the occurrences of biased behavior toward women in HRM practices. Besides, the cross-sectional research design was utilized to evaluate the research model. As a result, determining causality becomes difficult and is not clear. Future studies are recommended to use longitudinal research designs to interpret the pattern of relationships among study variables over time. This will clarify, integrate, and extend the work on the consequences of women discrimination in HRM practices by tracking the effects over time. Moreover, the data utilized to evaluate this research model was self-reported data with the potential for common method bias. To reduce such bias, future research must rely on data from multiple sources such as supervisors, HR managers, and male co-workers to examine their viewpoints regarding discrimination of women in HRM practices. This might involve more complexity in collecting data, but it may be a more objective way to measure the construct “women discrimination in HRM practices.” To represent the general banking sector in India, future research must consider other bank groups as well, namely—foreign banks, regional rural banks, and small finance banks. This in turn will improve the generalizability of the findings. To shed a holistic light on the construct “women discrimination in HRM practices” the future research model can include numerous psychological variables. These include employee engagement, job satisfaction, work motivation, employee performance, and organizational citizenship behavior and examine such linkages. Besides, the role of a supervisor’s gender must also be assessed regarding the differential treatment of women employees in the workplace contexts. Furthermore, the study was confined to Northern India which limits its cross-regional applicability. To enhance the generalizability of its findings, subsequent research should be extended to Southern, Central, Western, and Eastern regions of India as well.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Azra Khan  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4019-5813

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4019-5813

Riyaz Ahmad Rainayee  https://orcid.org/0009-0009-5940-5057

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-5940-5057

Appendix

Table A1. Generation of Scale Items for Women Discrimination in HRM Practices.

Table A2. Scale Items for Organizational Commitment.

Table A3. Factor Loadings of Indicators of Lower-Order Constructs.

.jpg/10_1177_25819542241276583-table13(1)__468x480.jpg)

Source: Smart PLS output.

Ackerman, R., Arabia, L., Lague, I., Mayhew, S., & Olsen, S. (2005). Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (CEDAW). https://www.lwv-fairfax.org/CEDAWl l-05Progl .pdf

Afza, S. R., & Newaz, M. K. (2008). Factors determining the presence of glass ceiling and influencing women career advancement in Bangladesh. BRAC University Journal, 5(1), 85–92.

Allen. (2006). Making sense of the barriers women face in the information technology work force: Standpoint theory, self-disclosure and causal maps. Springer Science and Business Media Inc, 54, 831–844.

Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Beacon Press.

Angel, H., & Perry, J. (1981). An empirical assessment of organisational commitment and organisational effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 2(6), 1–14.

Babic, A., & Hansez, I. (2021). The glass ceiling for women managers: Antecedents and consequences for work-family interface and well-being at work. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–17.

Barron, J. M., Black, D. A., & Lowenstein, M. A. (1993). Gender differences in training, capital and wages. The Journal of Human Resources, 2, 343–364.

Ben, S. L. (2008). Sex typing and the avoidance of cross sex behaviour. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 33, 48–54.

Bergman, B., & Hallberg, L. R. M. (2002). Women in a male dominated industry: Factor analyses of a woman workplace culture questionnaire based on a grounded theory model. Sex Roles, 46, 305–316.

Bezbaruah, S. (2012). Gender inequalities in India’s new service economy: A case study of the banking sector [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Queen Mary, University of London.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

Bobbitt-Zeher, D. (2011). Gender discrimination at work: Connecting gender stereotypes, institutional policies, and gender composition of workplace. Gender and Society, 25(6), 764–786.

Bollen, K. A., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2017). Notes on measurement theory or causal-formative indicators. Psychological Methods, 22(3), 605–608.

Branscombe, N. R., & Ellemers, N. (1998). Coping with group-based discrimination: Individualistic versus group level strategies. Academic Press.

Browne, I., & Kennelly, I. (1999). Stereotypes and realities: Images of black women in the labor market. Russell Sage Foundation.

Cascio, W. F. (1995). Managing human resource. McGraw-Hill.

Chen, Y., Zhang, Y., & Borken-Kleefeld, J. (2019). When is enough? Minimum sample sizes for on-road measurements of car emissions. Environmental Science & Technology, 53(22), 13284–13292.

Churchill Jr, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, XVI, 64–73.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Crosby, F. J. (1982). Relative deprivation and working women. Oxford University Press.

De Pater, I. E., Van Vianen, A. E. M., & Bechtoldt, M. N. (2010). Gender differences in job challenge: A matter of task allocation. Gender, Work and Organization, 17(4), 433–453.

Dickens, L. (1998). What HRM means for gender equality. Human Resource Management Journal, 8(1), 23–40.

Diekman, A. B., & Eagly, A. H. (2000). Stereotypes as dynamic constructs: Women and men of the past, present, and future. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(10), 1171–1188.

Dipboye, R. L., & Colella, A. (2005). Discrimination at work: The psychological and organizational bases. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dost, M. K., Zia-ur-Rehman, & Tariq, S. (2012). The organizations having high level of glass ceiling has lower productivity due to lack of employee commitment. Kuwait Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 1(8), 93–103.

Downes, M., Hemmasi, M., & Eshghi, G. (2014). When a perceived glass ceiling impacts organisational commitment and turnover intent: The mediating role of distributive justice. Journal of Diversity Management, 9(2), 131.

Dworkin, T. M., Schipani, C. A., Milliken, F. J., & Kneeland, M. K. (2018). Assessing the progress of women in corporate America: The more things change, the more they stay the same. American Business Law Journal, 55(4), 721–762.

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behaviour: A social-role interpretation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eghlidi, F. F., & Karimi, F. (2020). The relationship between dimensions of glass ceiling and organizational commitment of women employees. International Journal of Human Capital in Urban Management, 5(1), 27–34.

Elsawy, M. M., & Elbadawe, M. A. (2022). The impact of gender-based human resource practices on employee performance: An empirical analysis. International Journal of Business and Management, 17(6). https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v17n6p1

Ensher, E. A., Grant-Vallone, E. J., & Donaldson, S. I. (2001). Effects of perceived discrimination on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behaviour, and grievances. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 12, 53–72.

Estevez-Abe, M. (2005). Gender bias in skills and social policies: The varieties of capitalism perspective on sex segregation. Social Politics, 12, 180–215.

Feather, N. T., & Boeckmann, R. J. (2007). Beliefs about gender discrimination in the workplace in the context of affirmative action: Effects of gender and ambivalent attitudes in an Australian sample. Sex Roles, 57, 31– 42.

Foley, S., Hang-Yue, N., & Loi, R. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of perceived personal gender discrimination: A study of solicitors in Hong Kong. Sex Roles, 55, 197–208.

Foley, S., Hang-Yue, N., & Wong, A. (2005). Perceptions of discrimination and justice. Are there gender differences in outcomes? Group and Organisation Management, 30(4), 421–450.

Ghiat, H., & Zohra, M. F. (2023). Cultural pressures and the conflict of gender roles for working women in leadership positions: A field study of a sample of female leaders. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 7(2), 574–593.

Goldman, B., Gutek, B., Stein, J. H., & Lewis, K. (2006). Employment discrimination in organizations: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Management, 32, 786–830.

Gordon, J., & Gupta, P. (2004). Understanding India’s services revolution. International Monetary Fund.

Gutek, B. A., Cohen, A. G., & Tsui. A. (1996). Reactions to perceived discrimination. Human Relations, 49, 791–813.

Hair Jr, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed). Prentice-Hall.

Hair Jr, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson New International Edition.

Hair Jr, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2015). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

Hessaramiri, H., & Kleiner, B. H. (2001). Explaining the pay disparity between women and men in similar jobs. The International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 21, 8–10.

Hyde, J. S. (2005). The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychological Association, 60(6), 581–592.

Israel, G. D. (2003). Determining sample size. University of Florida.

Jain, N., & Mukherjee, S. (2010). The perception of glass ceiling in Indian organisations: An exploratory study. South Asian Journal of Management, 17(1), 23–42.

James, K., Lovato, C., & Cropanzano, R. (1994). Correlation and known-group comparison validation of a workplace prejudice/discrimination inventory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24, 1573–1592.

Jones, K. P., Arena, D. F., Nittrouer, C. L., Alonso, N. M., & Lindsey, A. P. (2017). Subtle discrimination in the workplace: A vicious cycle. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 10(1), 51–76.

Joplin, J. R. W., & Shaffer, M. A. (1997). Harassment, lies, theft, and other vexations: A cross cultural comparison of aggressive behaviors in the workplace. National Meetings of the Academy of Management.

Kaori, S., Yuki, H., & Hideo, O. (2017). Gender differences in careers. The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry. https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/

Khan, A., & Rainayee, R. A. (2020). The linkage between women discrimination in HRM practices and job-related outcomes: A conceptual study. In S. N. Mehta, & T. Rahman (Eds.), Emerging trends in commerce & management (pp.76–83). Empyreal Publishing House.

Khuong, M. N., & Chi, N. T. (2017). Effects of the corporate glass ceiling factors on female employee’s organizational commitment. Journal of Advanced Management Science, 5(4), 255–263.

Kiaye, R. E., & Singh, A. M. (2013). The glass ceiling: A perspective of women working in Durban. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 28(1), 28–42.

King, E. B., & Cortina, J. M. (2010). The social and economic imperative of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered supportive organizational policies. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 3, 69–78.

Kingsley, K., & Glynn, A. (1992). Women in the architectural workplace. Journal of Architectural Education, 46(1), 14–20.

Korabik, K., & Rosin, H. M. (1991). Workplace variables, affective responses, and intention to leave among women managers. Journal of Occupationa1 Psychology, 64(4), 317–330.

Lankford, S. V., & Howard, D. R. (1994). Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Annals of Tourism Research, 21, 121–139.

Lenhart, S., & Evans, C. (1991). Sexual harassment and gender discrimination: A primer for women physicians. Jam Med Womens Assoc, 46, 77–80.

Lyness, K. S., & Thompson, D. E. (1997). Above the glass ceiling? A comparison of matched samples of female and male executives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(3), 359–375.

McCauley, C. D., Ohlott, P. J., & Ruderman, M. N. (1999). Job challenge profile. Jossey-Bass and Pfeiffer.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1, 61–98.

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organisation and occupation: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 538–557.

Mowday, R. T., Steers, R. M., & Porter, L. W. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 14, 224–247.

Munda, S. S. (2016). Gender discrimination: A termite which destroys organizational commitment of female employees. Social Sciences International Research Journal, 2(1), 318–321.

Mwita, K., & Mwakasangula, E. (2023). Factors affecting women in acquiring leadership positions in workplaces: A human resource management perspective. Social Sciences, Humanities and Education Journal, 4(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.25273/she.v4i1.15602

Ngo, H. Y., Tang, C., & Au, W. (2002). Behavioral responses to employment discrimination: A study of Hong Kong workers. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13, 1206–1223.

Ngo, H. Y., Foley, S., Wong, A., & Loi, R. (2003). Who gets more of the pie? Predictors of perceived gender inequity at work. Journal of Business Ethics, 45, 227–241.

Olori, W. O., & Comfort, D. (2017). Workplace discrimination and employee commitment in Rivers State Civil Service, Nigeria. European Journal of Business and Management, 9(8), 51–57.

O’Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on pro social behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 492–499.

Parray, A. H., & Bhasin, J. (2013). Gender discrimination in workforce and discretionary work effort—A prospective approach. International Monthly Refereed Journal of Research in Management & Technology, 2.

Perlman, R., & Pike, M. (1994). Sex discrimination in the labour market: The case for comparable worth. Manchester University Press.

Phinney, J. S. (1992). The multi-group ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156–176.

Preenen, P. T. Y., De Pater, I. E., Van Vianen, A. E. M., & Keijzer, L. (2011). Managing voluntary turnover through challenging assignments. Group & Organization Management, 36(3), 308–344.

Qu, Y., Jo, W., & Choi, H. C. (2019). Gender discrimination, injustice, and deviant behavior among hotel employees: Role of organizational attachment. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 21(1), 1–27.

Ramya, K. R., & Raghurama, A. (2016). Women participation in Indian banking sector: Issues and challenges. International Journal of Science and Research Volume, 5(2), 1760–1763.

Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Jaafar, M., Kock, N., & Ahmad, A. G. (2017). The effects of community factors on residents’ perceptions toward world heritage site inscription and sustainable tourism development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(2), 198–216.

Reskin, B., & Padavic, I. (1994). Women and men at work. Pine Forge Press.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 698–714.

Richard, O. C., Roh, H., & Pieper, J. P. (2013). The link between diversity and equality management practice bundles and racial diversity in the managerial ranks: Does firm size matter? Human Resource Management, 52(2), 215–242.

Ridgeway, C., & England, P. (2007). Sociological approaches to sex discrimination in employment. Blackwell Publishing.

Rosen, B., & Jerdee, H. T. (1974). Influence of sex role stereotypes on personnel decisions. Journal of Applied Technology, 59(1), 9–14.

Salum, S. S. (2020). Factors influencing women access to leadership positions in Kisarawe district secondary schools [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Mzumbe University.

Sanchez, J. I., & Brock, P. (1996). Outcomes of perceived discrimination among Hispanic employees: Is diversity management a luxury or a necessity? Academy of Management Journal, 39, 704–719.

Sarstedt, M., Hair Jr, J. F., Cheah, J. H., Becker, J. M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australasian Marketing Journal, 27(3), 197–211.

Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Henseler, J., & Hair Jr, J. F. (2014a). On the emancipation of PLS-SEM: A commentary on Rigdon 2012. Long Range Planning, 47(3), 154–160.

Sattar, A., & Nawaz, A. (2011). Investigating the demographic impacts on the job satisfaction of district officers in the province of Pakistan. International Research Journal of Management and Business Studies, 1(3), 68–75.

Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Kobrynowicz, D., & Owen, S. (2002). Perceiving discrimination against one’s gender group has different implications for well-being in women and men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(2), 197–210.

Shaffer, M. A., Joplin, J. R., Bell, M. P., Lau, T., & Oguz, C. (2000). Gender discrimination and job-related outcomes: A cross-cultural comparison of working women in the United States and China. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 57(3), 395–427.

Sharma, S., & Kaur, R. (2019). Glass ceiling for women and work engagement: The moderating effect of marital status. F.I.I.B. Business Review, 8(2), 132–146.

Snizek, W., & Neil, C. (1992). Job characteristics, gender stereotypes, and perceived gender. Organization Studies, 13, 403–416.

Somers, M. J., & Birnbaum, D. (1998). Work-related commitment and job performance. It’s also the nature of the performance that counts. Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 19(6), 621–634.

Suliman, A., & Iles, P. (2000). Is continuance commitment beneficial to organisations? Commitment-performance relationship: A new look. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 15, 407–422.

Sunaryo, S., Rahardian, R., Risgiyanti., Suyono, J., & Usman, I. (2021). Gender discrimination and unfair treatment: Investigation of the perceived glass ceiling and women reactions in the workplace: Evidence from Indonesia. International Journal of Economics and Management, 15(2), 297–313.

Tlaiss, H. A., & Dirani, K. M. (2015). Women and training: An empirical investigation in the Arab Middle East. Human Resource Development International, 18(4), 1–21.

Townley, B. (1990). The politics of appraisal: lessons from the introduction of appraisals into U.K. universities’. Human Resource Management Journal, 1(1), 27–44.

Triana, M. D. C., Gu, P., Chapa, O., Richard, O., & Colella, A. (2021). Sixty years of discrimination and diversity research in human resource management: A review with suggestions for future research directions. Human Resource Management, 60, 145–204.

Triana, M. D. C., Jayasinghe, M., Pieper, J. R., Delgado, D. M., & Li, M. (2018). Perceived workplace gender discrimination and employee consequences: A meta-analysis and complementary studies considering country context. Journal of Management, 10(10), 1–29.

Turnley, W. H., Bolino, M. C., Lester, S. W., & Bloodgood, J. M. (2003). The impact of psychological contract fulfilment on the performance of in-role and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Management, 29, 187–206.

Uma, S. (2000). Women as a workforce: Discrimination in manufacturing sector, HRM perspective (Publication No. 373659) [Doctoral dissertation, Gujarat University]. ProQuest.

Welle, B., & Heilman, M. E. (2005). Formal and informal discrimination against women at work: The role of gender stereotypes (Vol. 5). Information Age Publishers.

Yamane, T. (1967). Elementary sampling theory. Prentice-Hall.