1 Houston Community College, Houston, Texas, USA

2 Current Affiliation: Lone Star College, Cypress, TX, USA

3 The City University of New York, Brooklyn College, New York, USA

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Although Vietnam has attracted significant foreign investment in recent years, many Western companies continue to face challenges in building trust and cultivating meaningful relationships due to a limited understanding of local customs. The concept of Quan He, while central to Vietnamese business practices, remains largely undertheorized in academic literature. While much has been written about China’s Guanxi and Western Relationship Marketing (RM), Vietnam’s Quan He offers a distinct relational framework shaped by the country’s dual ideological economy and cultural values.

This study explores the foundational elements of Quan He: The Dien (face-saving), Co Qua Co Lai (reciprocity), and Tinh Cam (emotional bonding), and compares them to Guanxi’s Mianzi, Renqing, and Ganqing, as well as the core principles of RM such as communication, reciprocity, and bonding. Drawing on both theoretical analysis and empirical data collected from Vietnam, the United States, and Bangladesh, I propose a culturally grounded framework and introduce a validated scale to measure the three facets of Quan He. The findings provide important insights for international firms seeking to operate successfully in Vietnam by helping them navigate relationships and avoid common cultural missteps.

Vietnamese business culture, Quan He, foreign investment, relationship marketing, Guanxi

Introduction

This manuscript builds on an earlier version published in a local conference journal (Pham, 2024).1 The current version significantly expands the theoretical framing, revises the structure for an international business audience, and deepens the discussion with broader implications for foreign investors operating in emerging markets. Although Vietnam continues to draw substantial foreign investment, many Western firms struggle to establish trust and meaningful connections due to a limited grasp of local cultural norms. Quan He, a concept central to doing business in Vietnam, remains insufficiently developed in existing scholarship. While Guanxi and relationship marketing (RM) have been widely studied, Quan He has received little academic attention. As Vietnam becomes increasingly significant in global trade and operates within a unique dual ideological system, gaining a deep understanding of Quan He is crucial for foreign companies seeking to navigate the local business environment effectively and avoid cultural pitfalls.

Building and maintaining solid customer relationships is pivotal for enhancing firm performance and ensuring customer satisfaction, especially in emerging economies where personal relationships and networks are vital for business success (Ndubisi & Wah, 2005; Shaalan et al., 2013). The East and West have distinct approaches to building these relationships, known as Guanxi and RM. Grasping the nuances of these practices can offer cross-national companies a competitive edge by catering to diverse customer needs.

However, it is essential to note that Guanxi does not encapsulate all Eastern business relationship types. Vietnam, for instance, blends elements from both Guanxi and RM (Do et al., 2007; Nguyen Hau & Viet Ngo, 2012; Smith & Pham, 1996). The nation’s shift from a centrally planned economy to a socialist market economy two decades ago (Beresford, 2008) has led to a unique blend of ideologies. This change has resulted in regional disparities, a new social class structure, and challenges in establishing a comprehensive legal framework (Nguyen, 2005). Consequently, Guanxi-style relationships have become crucial for business in Vietnam (Do et al., 2007).

In Vietnam, the cultural custom of Quan He, akin to Guanxi, emphasizes the significance of business relationships (Le & Nguyen, 2009). This practice, deeply rooted in Confucian philosophy, has several non-verbal rules that, if breached, can have severe repercussions. Despite its importance, more business research regarding Quan He needs to be conducted, highlighting the need for further study.

Quan He shares similarities with Guanxi in China, Kankei in Japan, and Kwan-kye in Korea. All these practices underscore the power of relationships in business. Given Vietnam’s unique societal backdrop, examining Quan He in the context of both Guanxi and RM is beneficial.

This study seeks to bridge Quan He and Guanxi with RM. We aim to explore:

To address these research questions, we will review the literature in the mentioned areas, comparing facets across Vietnamese, Chinese, and Western business practices. We have also gathered data from Eastern and Western countries to assess the impact of Quan He’s components on consumer purchase intentions. The study concludes with recommendations for Western entrepreneurs aiming to succeed in Vietnam.

Theoretical Foundation

The significance of Guanxi in influencing performance has been widely discussed in academic literature. Various theories have been employed to elucidate the Guanxi-performance linkage, including social capital theory, social network theory, social embeddedness theory, transaction cost economics, and the resource-based view (Tang & Cheng, 2012). Among these, social capital and network theories are particularly relevant for our study, as they emphasize the role of social ties and networks in shaping business outcomes.

Social Capital Theory

Social capital theory posits that social ties, viewed as a form of social capital, facilitate the creation of valuable resources, leading to positive outcomes (Adler & Kwon, 2000; Burt, 2017). Such ties grant privileged access to information and opportunities (Inkpen & Tsang, 2005). Defined as a resource derived from social relationships (Granovetter, 1977), social capital encompasses cognitive, relational, and structural dimensions (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). This study focuses on the structural dimension, which pertains to relationship patterns.

Guanxi can bolster firms’ competitive advantages as a form of social capital by facilitating access to favors, resources, and protection (Luo, 1997; Park & Luo, 2001; Peng & Luo, 2000). Leveraging Guanxi, firms can efficiently control resources, garner crucial information, and foster business collaborations, thereby enhancing performance (Park & Luo, 2001).

Social Network Theory

Social network theory delves into the formation and impact of social relationships (Kadushin, 2004; Krause et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2017). It categorizes networks into ego-centric (individual connections), socio-centric (within organizations), and open-system networks (inter-organizational) (Kadushin, 2004). This study emphasizes ego-centric networks, exploring individual relationships like those between salespersons and customers.

Guanxi, deeply rooted in collectivist societies, can be seen as an early form of social network theory (Hampden-Turner & Trompenaars, 2002). In this context, Guanxi components like Mianzi and Renqing align with weak ties characterized by short-term, distant interactions. In contrast, Ganqing, the highest Guanxi level, aligns with solid ties, denoting long-lasting, trustworthy relationships.

From RM to Guanxi and Quan He

RM, emphasizing long-term customer relationships, has gained prominence since the 1990s (Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Palmatier et al., 2006). While RM often pertains to organizational relationships, it can also apply to individual interactions. On the other hand, Guanxi operates at a personal level, representing individual social capital (Fan, 2002b; Wang, 2007).

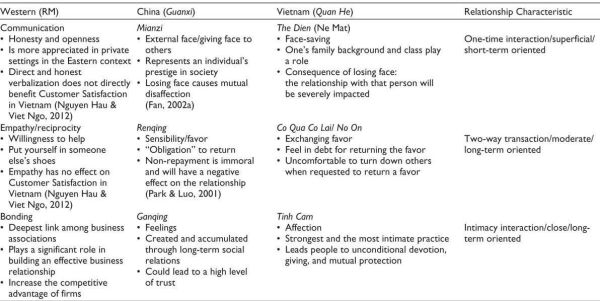

To comprehend Quan He’s compatibility with Guanxi, this study juxtaposes Quan He facets with Guanxi constructs and key RM components. Table 1 compares the key components of Quan He with Guanxi and Western Relationship Marketing. It highlights how Vietnamese business culture blends Eastern and Western relational norms, particularly in communication, reciprocity, and emotional bonding.

Table 1. Compare Quan He with Relationship Marketing and Guanxi.

Communication, Mianzi (Guanxi), and Dien (Quan He)

Communication is pivotal in forming strong relationships between buyers and sellers. Effective communication can resolve disputes and foster trust and commitment (Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Palmatier et al., 2006). However, in East Asian cultures like China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, preserving one’s reputation or “face” is paramount. This concept is termed Mianzi in China and Dien in Vietnam. Both emphasize the importance of maintaining one’s social standing and dignity in public (Leung & Cohen, 2011; Pham, 2014).

In these cultures, direct criticism can be seen as a loss of face. Therefore, disagreements are often handled privately to avoid public embarrassment (GoinGlobal, 2015). Vietnamese proverbs like “M.png) t lòng tr

t lòng tr.png) c,

c, .png) c lòng sau” and “Thu

c lòng sau” and “Thu.png) c

c .png) ng dã t

ng dã t.png) t, s

t, s.png) th

th.png) t m

t m.png) t lòng” emphasize the value of honesty and careful communication.

t lòng” emphasize the value of honesty and careful communication.

Reciprocity, Renqing (Guanxi), and Co Qua Co Lai (Quan He)

Co Qua Co Lai in Vietnamese culture mirrors the concept of Renqing in Chinese Guanxi. Both emphasize the importance of reciprocity and empathy in relationships. In both cultures, favors are expected to be returned, though not necessarily immediately (Barbalet, 2021; Yen et al., 2017; Zhao & Zhang, 2020). This facet of the relationship is more profound than the first, requiring multiple exchanges of favors.

Bonding, Ganqing (Guanxi), and Tinh Cam (Quan He)

Tinh Cam in Vietnamese culture resembles Ganqing in Chinese Guanxi, representing deep emotional bonds formed over time. Such bonds are more substantial than mere reciprocity and involve mutual trust and protection. This concept aligns with the “bonding” dimension in RM, which emphasizes unified actions to achieve mutual goals (Sin et al., 2006). However, the intimacy in Ganqing or Tinh Cam is more profound than in Western “bonding.”

Methodology

The methodology here entailed developing a novel scale to gauge the concept of Quan He, complemented by surveys to delve into the intricacies of these cultural notions across various contexts.

Building a New Scale to Measure the Three Facets: The Dien, Co Qua Co Lai, and Tinh Cam

Communication is pivotal in relationship-building, encompassing the quality, frequency, and amount of information exchanged between parties (Anderson & Weitz, 1992; Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Palmatier et al., 2006). Effective communication is instrumental in resolving disputes and fostering solid relationships (Anderson & Narus, 1990; Palmatier et al., 2006). However, in East Asian cultures, including China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, there is a significant emphasis on preserving one’s reputation and avoiding public embarrassment. This cultural nuance is termed Mianzi in China and Dien in Vietnam. Both concepts revolve around maintaining one’s public image, dignity, and honor (Bedford, 2011; Hwang, 1987; Leung & Cohen, 2011; Pham, 2014; Wang, 2007).

Like Renqing in Chinese culture, Co Qua Co Lai embodies the principle of reciprocal favor. In Chinese culture, Renqing is twofold: it signifies an individual’s emotional response to daily situations and is closely tied to reciprocity (Hwang, 1987; Wang, 2007). Similarly, in Vietnam, there is a strong cultural emphasis on returning favors (Zhou & Bankston, 1998). The essence of this facet is captured in the Vietnamese proverb, “Có .png) i có ll mm tool lòng nhau,” emphasizing the harmony achieved through reciprocal exchanges.

i có ll mm tool lòng nhau,” emphasizing the harmony achieved through reciprocal exchanges.

Tinh Cam, synonymous with Ganqing in Chinese culture, represents the emotional bonds formed within networks. It is the pinnacle of relationship facets, cultivated through enduring social interactions and often characterized by unwavering loyalty (Zhang & Wang, 2007). In the Vietnamese context, Tinh Cam signifies deep emotional connections, mutual protection, and implicit trust among closely-knit groups. This facet mirrors the bonding dimension in RM, which emphasizes unified actions to achieve mutual goals (Sin et al., 2005).

Summary

The three facets of Quan He, juxtaposed with RM and Guanxi components, offer a comprehensive understanding of relationship dynamics in the Vietnamese context. The Dien facet underscores the importance of communication and face-saving, the Co Qua Co Lai facet emphasizes reciprocity and empathy, and the Tinh Cam facet encapsulates deep bonding and affection.

Empirical Study

Research Design & Measures

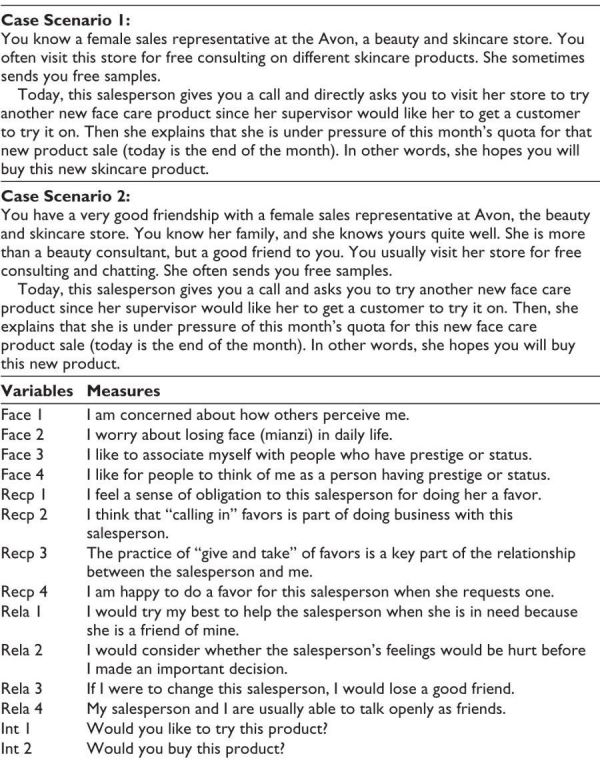

Table 2 outlines the case scenarios used in the survey along with the corresponding measurement items for each construct. The scenarios reflect different levels of relationship closeness, while the items measure face-saving, reciprocity, relationship, and customer intention. The data for this study were collected from the US, Bangladesh, and Vietnam. While Guanxi is a Chinese concept, its principles are reflected in many East Asian cultures, making it relevant for a broader study.

The United States and Vietnam were selected for cross-cultural comparison due to their contrasting cultural orientations, with the US representing individualism and Vietnam representing collectivism. Bangladesh was included to assess the construct within its native socio-cultural context.

We decided to use a cosmetic product as our survey scenario because it involves a relationship between buyer and seller and is familiar to our respondents. Since no existing scales were available for our study, we developed measurement scales by adapting items from Yen et al. (2011) and consulting experts in the field. All measures were analyzed for validity and reliability by following the guidelines from Anderson and Gerbing (1988). We pre-tested the questionnaire among convenience samples and made necessary modifications. We then distributed the questionnaire to respondents in the USA and Bangladesh.

In the questionnaire, respondents were presented with a scenario and asked to respond to the questions. Respondents rated the questions on a five-point Likert scale. Each item is assigned a numerical value of 1 with a verbal statement “highly disagree” and a numerical value of 5 with a verbal statement “highly agree.” A multi-item scale was used to measure each construct to assess reliability and validity. The dependent variable, intention, was measured through two items. Demographic variables are also collected from the respondents.

Data Collection

Data was collected from one large public university in each of the USA, Vietnam, and Bangladesh. Students majoring in business were invited to participate in the survey. Though participation was entirely voluntary, bonus points were provided as an incentive. Respondent’s anonymity is maintained by not providing any identification in the survey questionnaire.

Table 2. Case Scenarios and Measures.

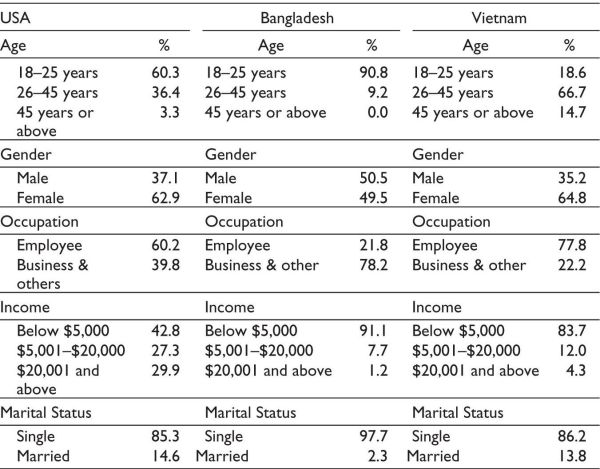

A total of 123 responses were collected from the USA. Likewise, 87 and 108 responses were collected from Bangladesh and Vietnam, respectively. Respondent’s characteristics are depicted in Table 3.

Table 3. Sample Characteristics (USA, Bangladesh, and Vietnam).

Analyses

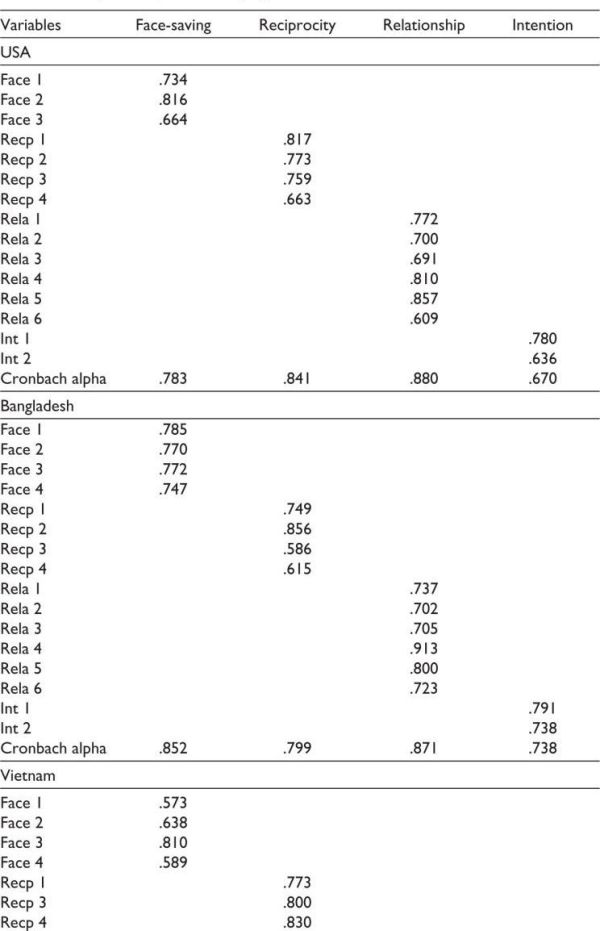

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted to investigate whether the measures used in this study loaded on expected variables. Even though items were adapted from existing scales, EFA was necessary to validate construct structure in a new cultural context and to ensure the proper loading of our novel constructs, specifically the three facets of Quan He.

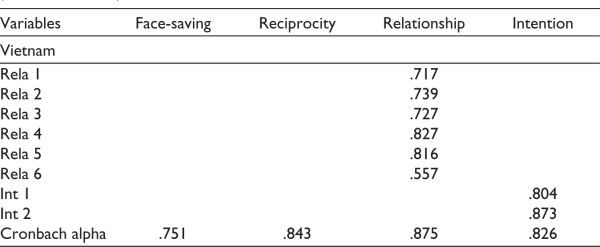

As expected, four factors were confirmed (Table 4). The eigenvalue of each factor is greater than 1. The cumulative variation was maintained by more than 60%. Table 4 contains the factor loadings, reliability coefficients, and average variance extracted (AVE).

Table 4. Factor Analysis of Independent Variables with Varimax Rotation (Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis).

Reliability

The reliability of each multi-item factor is evaluated through Cronbach’s alpha. In other words, Cronbach’s Alpha was computed to ensure internal consistency of items after cultural adaptation, as reliability can vary across samples and settings.

Cronbach’s alpha value should be greater than .7 (Nunnally, 1978). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha value is more significant than .70 for each of the four factors. Reliability analysis shows that the internal consistency of multi-item measures is relatively high.

Validity

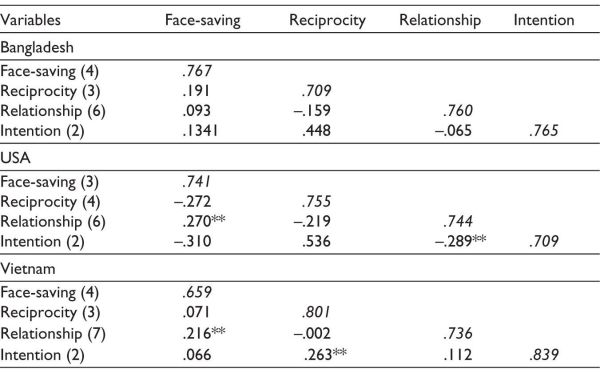

Discriminant validity is assessed through AVE scores. Discriminant validity shows that one factor is different from any other factor. The AVE value should exceed .50 (Hair et al., 2010). AVE values in this study are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Correlation Results.

Notes: Figures in italics represent the square root of AVE.

Figures in parentheses indicate the number of items measuring each construct.

p .png) .05.

.05.

**Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2-tailed).

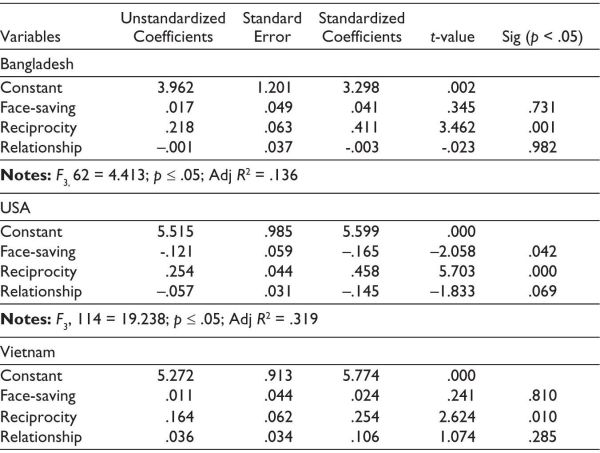

Regression Analysis

Table 6 presents the detailed results of the multiple regression analysis across Bangladesh, the USA, and Vietnam. Reciprocity is the only consistent and significant predictor of customer intention in all three countries. Face-saving negatively predicts intention only in the USA, while relationships shows no significant influence in any country. Multiple regression analysis was used to test the impact of three facets on customers’ behavioral intention. Statistical results derived from the collected data from all three countries show that the entire model is significant, as shown by the overall F-statistic (p .png) .05). The regression model shows that the independent variables explain 13.6%, 31.9%, and 5% of the variation of the dependent variable, intention, as shown in the R2 value in Bangladesh, USA, and Vietnam, respectively. Multiple regression result shows that reciprocity has the most substantial positive impact on customer intention in all three countries shown [β (USA) = .458; β (Bangladesh) = .411; β (Vietnam) = .254]. Using data from the USA shows that face-saving has a negative impact on consumer intention (β = –.165; p

.05). The regression model shows that the independent variables explain 13.6%, 31.9%, and 5% of the variation of the dependent variable, intention, as shown in the R2 value in Bangladesh, USA, and Vietnam, respectively. Multiple regression result shows that reciprocity has the most substantial positive impact on customer intention in all three countries shown [β (USA) = .458; β (Bangladesh) = .411; β (Vietnam) = .254]. Using data from the USA shows that face-saving has a negative impact on consumer intention (β = –.165; p .png) .05). However, we failed to find statistical significance of the relationship between face-saving and customer intention in Vietnam and Bangladesh (β = .041; p

.05). However, we failed to find statistical significance of the relationship between face-saving and customer intention in Vietnam and Bangladesh (β = .041; p .png) .05 and β = .024; p

.05 and β = .024; p .png) .05, respectively). Though weak, the relationship has a negative impact on consumer intention (β = –.145; p < .10) in the USA. The data collected from the USA shows that the relationship negatively impacts consumer intention. However, the independent variable, relationship, does not statistically support the dependent variable, intention, in both Bangladesh and Vietnam (β = –.003; p

.05, respectively). Though weak, the relationship has a negative impact on consumer intention (β = –.145; p < .10) in the USA. The data collected from the USA shows that the relationship negatively impacts consumer intention. However, the independent variable, relationship, does not statistically support the dependent variable, intention, in both Bangladesh and Vietnam (β = –.003; p .png) .05 and β = .106; p

.05 and β = .106; p .png) .05, respectively).

.05, respectively).

Table 6. Multiple Regression Results (Dependent Variable: Intention).

Notes: F3, 99 = 2.791; p .png) .05; Adj R2 = .050

.05; Adj R2 = .050

Discussion

We tested a model of customers’ behavioral intentions with the data collected from the USA, Bangladesh, and Vietnam. The statistical results indicate that the model explains customers’ intentions well. Findings suggest that a customer’s intention is predicted by three significant variables: face-saving, reciprocity, and relationship. Therefore, managers should focus on these three critical predictors to instigate customers to purchase (Ding et al., 2017; Mende et al., 2013; Zhao & Zhang, 2020).

The standardized regression coefficients show that reciprocity is the most critical variable influencing customer intention in all three countries. Reciprocity has a more substantial positive influence on customer intention in the USA than in Vietnam and Bangladesh [β (USA) = .458; β (Bangladesh) = .411; β (Vietnam) = .254]. This finding is consistent with the study of Davies et al. (1995), which suggests that reciprocity is a universal norm influencing customer intention across cultures.

Face-saving has a negative influence on customers’ intentions in the USA. This finding is consistent with the study of O’Malley and Tynan (2000), which suggests that face-saving is not a significant predictor of customer intention in Western cultures. However, in Asian cultures, face-saving is an essential predictor of customer intention (Siu et al., 2016; Wei & Sung, 2017). This finding suggests managers should be cautious when using face-saving strategies in Western cultures.

The relationship has a weak negative influence on customers’ intentions in the USA. This finding is consistent with Li et al.’s (2008) study, which suggests that relationship is not a significant predictor of customer intention in Western cultures. However, in Asian cultures, relationship is an essential predictor of customers’ intention. This finding suggests that managers should focus on building solid relationships with customers in Asian cultures.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides insights into the predictors of customer intention in different cultures. The findings suggest that managers should focus on reciprocity, face-saving, and relationship to influence customers’ intentions. The study also highlights the importance of understanding cultural differences when designing marketing strategies.

Theoretical and Managerial Implications

Understanding Quan He is essential for fostering business relationships in Vietnam, especially for Western entrepreneurs entering the Vietnamese market. This study stands as the inaugural comprehensive analysis of Quan He, offering these notable contributions:

In short, this exploratory study contributes by offering (a) a new construct, Quan He, that bridges Eastern and Western relationship paradigms; (b) a validated measurement model of its three facets; and (c) actionable insights for multinational firms entering Vietnam.

Limitations and Future Research

While this study offers a pioneering perspective on Quan He, it is not without its constraints. The data were collected from one university in each country, which limits generalizability. However, this exploratory study provides foundational insights for future research with broader, more representative samples.

We have pinpointed the commonalities and distinctions between Quan He, Guanxi, and RM. The tri-faceted nature of Quan He was explored in detail and compared with corresponding facets in Guanxi.

Our empirical evaluation compared the effects of these facets on consumer intent in Bangladesh (Eastern) and the USA (Western). However, the results from these two countries might be different. Future studies might consider other influencing elements like purchasing power or broaden the product scope beyond cosmetics. We advocate for expanding this model into diverse cultural landscapes to validate its generalizability.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Ngoc Cindy Pham  https://orcid.org/0009-0004-3401-8695

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-3401-8695

Note

Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S. W. (2000). Social capital: The good, the bad, and the ugly. In E. Lesser (Ed.), Knowledge and social capital (pp. 89–115). Academic Press.

Anderson, E., & Weitz, B. (1992). The use of pledges to build and sustain commitment in distribution channels. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(1), 18–34.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Anderson, J. C., & Narus, J. A. (1990). A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 42–58.

Barbalet, J. (2021). Where does guanxi come from? Bao, shu, and renqing in Chinese connections. Asian Journal of Social Science, 49(1), 31–37.

Bedford, O. (2011). Guanxi-building in the workplace: A dynamic process model of working and backdoor guanxi. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(1), 149–158.

Beresford, M. (2008). .png) i M

i M.png) i in review: The challenges of building market socialism in Vietnam. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 38(2), 221–243.

i in review: The challenges of building market socialism in Vietnam. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 38(2), 221–243.

Burt, R. S. (2017). Structural holes versus network closure as social capital. In Social capital (pp. 31–56). Routledge.

Co qua co lai moi toai long nhau. (2010, November 12). Báo M.png) i. Retrieved, 8 March 2025, from http://www.baomoi.com/co-di-co-lai-moi-toai-long-nhau/c/5184628.epi

i. Retrieved, 8 March 2025, from http://www.baomoi.com/co-di-co-lai-moi-toai-long-nhau/c/5184628.epi

Davies, H., Leung, T. K. P., Luk, S. T. K., & Wong, Y. H. (1995). The benefits of “guanxi”: The value of relationships in developing the Chinese market. Industrial Marketing Management, 24(3), 207–214.

Ding, G., Liu, H., Huang, Q., & Gu, J. (2017). Moderating effects of guanxi and face on the relationship between psychological motivation and knowledge-sharing in China. Journal of Knowledge Management, 21(5), 1077–1097.

Do, T., Quilty, M., Milner, A., & Longstaff, S. (2007). Business culture issues in Vietnam: Case studies.

Fan, Y. (2002a). Ganxi’s consequences: Personal gains at social cost. Journal of Business Ethics, 38(4), 371–380.

Fan, Y. (2002b). Questioning guanxi: Definition, classification and implications. International Business Review, 11(5), 543–561.

GoinGlobal. (2015, February 21). Vietnam: The concept of face. Retrieved, 8 March 2025, from http://www.goinglobal.com/articles/1500/

Granovetter, M. S. (1977). The strength of weak ties. In Social networks (pp. 347–367). Academic Press.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson.

Hampden-Turner, C. M., & Trompenaars, F. (2002). A mirror-image world: Doing business in Asia. In N. Bhagat & R. Steers (Eds.), Managing across cultures: Issues and perspectives (2nd ed., pp. 143–167). Thomson.

Hwang, K. K. (1987). Face and favor: The Chinese power game. American Journal of Sociology, 92(4), 944–974.

Inkpen, A. C., & Tsang, E. W. K. (2005). Social capital, networks, and knowledge transfer. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 146–165.

Kadushin, C. (2004). Introduction to social network theory (Working paper).

Krause, J., Croft, D. P., & James, R. (2007). Social network theory in the behavioural sciences: Potential applications. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 62, 15–27.

Le, N. T., & Nguyen, T. V. (2009). The impact of networking on bank financing: The case of small and medium-sized enterprises in Vietnam. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(4), 867–887.

Leung, A. K. Y., & Cohen, D. (2011). Within- and between-culture variation: Individual differences and the cultural logics of honor, face, and dignity cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(3), 507.

Li, J. J., Poppo, L., & Zhou, K. Z. (2008). Do managerial ties in China always produce value? Competition, uncertainty, and domestic vs. foreign firms. Strategic Management Journal, 29(4), 383–400.

Liu, W., Sidhu, A., Beacom, A. M., & Valente, T. W. (2017). Social network theory. In The international encyclopedia of media effects (pp. 1–12). Wiley.

Luo, J. D. (1997). The significance of networks in the initiation of small businesses in Taiwan. Sociological Forum, 12(2), 297–317.

Mende, M., Bolton, R. N., & Bitner, M. J. (2013). Decoding customer–firm relationships: How attachment styles help explain customers’ preferences for closeness, repurchase intentions, and changes in relationship breadth. Journal of Marketing Research, 50(1), 125–142.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266.

Ndubisi, N. O., & Wah, C. K. (2005). Factorial and discriminant analyses of the underpinnings of relationship marketing and customer satisfaction. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 23(6/7), 542–557.

Nguyen, T. V. (2005). Learning to trust: A study of inter-firm trust dynamics in Vietnam. Journal of World Business, 40(2), 203–221.

Nguyen Hau, L., & Viet Ngo, L. (2012). Relationship marketing in Vietnam: An empirical study. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 24(2), 222–235.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

O’Malley, L., & Tynan, C. (2000). Relationship marketing in consumer markets: Rhetoric or reality? European Journal of Marketing, 34(7), 797–816.

Palmatier, R. W., Dant, R. P., Grewal, D., & Evans, K. R. (2006). Factors influencing the effectiveness of relationship marketing: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing, 70(4), 136–153.

Park, S. H., & Luo, Y. (2001). Guanxi and organizational dynamics: Organizational networking in Chinese firms. Strategic Management Journal, 22(5), 455–477.

Peng, M. W., & Luo, Y. (2000). Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 486–501.

Pham, H. N. (2014). How do the Vietnamese lose face? Understanding the concept of face through self-reported face loss incidents. International Journal of Language and Linguistics, 2(3), 223–231.

Pham, N. C. (2024). Three facets of Quan-He (Vietnam) and Guanxi (China) define relationship marketing in Asian markets. Midwest Law Journal of the Academy of Legal Studies in Business, Conference Proceedings.

Shaalan, A. S., Reast, J., Johnson, D., & Tourky, M. E. (2013). East meets West: Toward a theoretical model linking guanxi and relationship marketing. Journal of Business Research, 66(12), 2515–2521.

Sin, L. Y. M., Tse, A. C. B., Chan, H., Heung, V. C. S., & Yim, F. H. K. (2006). The effects of relationship marketing orientation on business performance in the hotel industry. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 30(4), 407–426.

Sin, L. Y. M., Tse, A. C. B., Yau, O. H. M., Chow, R. P. M., Lee, J. S. Y., & Lau, L. B. Y. (2005). Relationship marketing orientation: Scale development and cross-cultural validation. Journal of Business Research, 58(2), 185–194.

Siu, N. Y. M., Kwan, H. Y., & Zeng, C. Y. (2016). The role of brand equity and face saving in Chinese luxury consumption. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(4), 245–256.

Smith, E. D., Jr., & Pham, C. (1996). Doing business in Vietnam: A cultural guide. Business Horizons, 39(3), 47–52.

Tang, W., & Cheng, Q. (2012). How business guanxi affects a firm’s performance: A study on Chinese small and medium-sized construction companies. (Master’s thesis, Uppsala University). DiVA. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:534510/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Wang, C. L. (2007). Guanxi vs. relationship marketing: Exploring underlying differences. Industrial Marketing Management, 36, 81–86.

Wei, X., & Jung, S. (2017). Understanding Chinese consumers’ intention to purchase sustainable fashion products: The moderating role of face-saving orientation. Sustainability, 9(9), 1570.

Xin, K. K., & Pearce, J. L. (1996). Guanxi: Connections as substitutes for formal institutional support. Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1641–1658.

Yen, D. A., Abosag, I., Huang, Y. A., & Nguyen, B. (2017). Guanxi GRX (ganqing, renqing, xinren) and conflict management in Sino-US business relationships. Industrial Marketing Management, 66, 103–114.

Yen, D. A., Barnes, B. R., & Wang, C. L. (2011). The measurement of guanxi: Introducing the GRX scale. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(1), 97–108.

Zhang, H. E., & Wang, Q. G. (2007). The extension of strong reciprocity theory. China Industrial Economy, 3, 17–24.

Zhao, H., & Zhang, M. (2020). The role of guanxi and positive emotions in predicting users’ likelihood to click the like button on WeChat. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1736.

Zhou, M., & Bankston, C. (1998). Growing up American: How Vietnamese children adapt to life in the United States. Russell Sage Foundation