1Birla Institute of Management Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

2Ex-cofounder, QorQl (HealthTech Startup), Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

India is in a state of distinctive paradox. On one side, it is ranked the fifth largest economy in the world with the aim to be among the top three by 2030, while on the other hand, the country’s equally important health sector lags and is ranked 145 among 195 countries on the Healthcare Access and Quality Index (HAQ; GBD 2016 Healthcare Access and Quality Collaborators, 2018). Despite significant thrust on healthcare and reforms over the last decade that have positively impacted life expectancy, helped lower infant mortality rate and provided better health coverage due to government initiatives like Ayushman Bharat and the National Health Mission, healthcare in India still faces critical challenges and is crippled with many deficiencies around health quality, accessibility, affordability and safety. This perspective article explores the opportunities and challenges in healthcare delivery in India and why it is imperative to implement a framework for connecting all the stakeholders in the healthcare ecosystem to facilitate equitable access to quality and affordable healthcare. The article also reflects on models of collaboration, connected health and coopetition to strengthen and streamline the healthcare sector for improved outcomes.

Healthcare, start-up, India, connected health, digitisation, coopetition

Introduction

Health is fundamental to a quality life. However, India’s healthcare economy faces significant challenges, including a fragile system with numerous barriers such as skewed doctor-patient ratio, urban-rural divide, lack of disease awareness, inadequate infrastructural facilities, trained workforce and lack of timely intervention to name a few. We have seen our health infrastructure crumble during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic as we lost numerous lives due to a lack of beds, oxygen, medicines and medical support, and our hospitals were painfully overflowing. The strong gaps and cracks in our healthcare systems stared at us, throwing up many questions as we agonisingly struggled through the crisis. The health crises over the two years, from 2020 to 2022, brought us to an inflection point. Despite having executed stringently towards subverting it and initiating comprehensive reforms to enhance healthcare, it is now imperative that we take an end-to-end look at our healthcare systems and resources to bring in a much-needed complete overhaul. Neglecting the sector could throttle the long-run growth of the country.

Healthcare is one of the largest sectors in the Indian economy in terms of both revenue and the number of people employed. It was expected to have an annual compounded growth rate of around 22% since 2016 (Sarwal et al., 2021). The e-health market, which has already gained substantial momentum, is also expected to reach US$10.6 billion by 2025 (Ibef.org, 2021). India is also among the fastest digital adopters in the world, with half a billion internet users, 350 million smartphone users, an overwhelming rise in tech start-ups and India-trained CEOs (Ranganathan, 2020).

The healthcare start-up ecosystem has also taken huge strides over the last two decades and is on the verge of reaching a new level of maturity. Though the first generation of start-ups in healthcare were mainly focused on providing EMR systems copied from the West, health-tech start-ups in India are now offering an array of solutions in the health space, spanning clinic management software for doctors, online consultations, follow-ups and medicine delivery. More so, wearable data is being used to analyse, design and recommend personalised services for proactive health, artificial intelligence is being used for effective diagnosis and deep learning is being used to better comprehend X-rays and imaging scans. Telehealth start-ups are facilitating the remote treatment of patients using consultations. Many start-ups are also providing healthcare at home for the elderly and patients with mobility constraints (Inc42.com, 2020).

The pharma sector is also being reshaped with the latest regulations to bring costs under control. Local pharmacies are being given competition by e-pharmacies, which offer convenience and affordability to patients. Large diagnostics players are also expanding their footprint by adopting a ‘hub and spoke’ business model with large centralised facilities for diagnostics and local collection centres. A few start-ups aggregating small players and home collections are being offered for convenience and an interesting competition is on.

The above transformations were catalysed by the healthcare reforms that were introduced in India around 2005. The reforms had a multi-pronged focus across strengthening rural health services National Rural Health Mission (NHRM), Universal Health Coverage (UHC) for standardising and benchmarking healthcare (NABH, IPHS, CEA) and establishing institutions like AIIMS and Medical Colleges across the country under the Pradhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Yojna. The Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY), popularly known as the Ayushman Bharat Yojana Scheme, is a flagship scheme that aims to provide health insurance and financial protection to the underprivileged. The Government has also introduced few reforms with respect to digitization of healthcare under the Digital India campaign (Ranganathan, 2020).

Despite all these efforts and initiatives, India needs to achieve much more to be a healthy nation. Countries like Maldives, Bhutan and Nepal are faring better in curbing tuberculosis and premature deaths because of non-communicable diseases in comparison to India, despite a decade of ambitious National Health Mission implementation (Gopal, 2019). Thailand and Vietnam have also achieved superior health outcomes as compared to India by consistently investing in their health systems. They have also implemented multisector initiatives aimed at improving availability of clean drinking water, sanitation amenities, education and improved nutrition. Their health insurance schemes cover close to 75% and 87% of the population, respectively, while in India, the penetration of health insurance stood at just around 35% in the financial year 2018 (India: Health insurance penetration, 2018, 2019). India also lags in the number of hospital beds per thousand population (0.5) in comparison to a few of the lesser developed countries like Bangladesh (0.87), Kenya (1.4) and Chile (2.1) (Worldbank.org). What is even more concerning is that, India spent just 4% of its budget on health as it moved into the pandemic, which is the fourth lowest in the world (Martin et al., 2020). India was also reported among the top five least-performing countries in handling the coronavirus crisis (Howell, 2021).

The above makes it apparent that there is something considerable beyond just healthcare reforms, digitisation efforts and investments that need to be addressed to move the health needle significantly. This article explores the need to identify and address the underlying issues in healthcare that are inhibiting the overall improvement of healthcare in a meaningful way. It is the precise time to have collaborative ownership and effort from all stakeholders, including government agencies, healthcare providers, community organisations and individuals, to identify and address issues to improve healthcare outcomes and ensure everyone can access high-quality healthcare services across primary, secondary and tertiary care settings.

The rest of the article is organised as follows. We provide background and discuss the major challenges of healthcare in India in the section ‘Background and Major Challenges’. An integrative approach for healthcare is presented in section ‘Rethinking Healthcare: An Integrated Approach’. Section ‘Conclusion, Limitations and Way Forward’ concludes.

Background and Major Challenges

In India, healthcare services are provided by the government as well as the private sector. Government services are hugely subsidised, while the private sector in health functions more like a free market despite being largely regulated (Rajagopalan & Choutagunta, 2020). Rural healthcare is a three-tier system consisting of Sub-Centres, Primary Health Centres (PHC) and Community Health Centres (CHC). Every tier is faced with shortages in health facilities to the tune of 18% at the Sub-Centre level, 22% at the PHC level and 30% at the CHC level (Rekha, 2020).

As of 2021, approximately 65% of India’s population lives in rural areas, according to the World Bank. According to the National Health Profile 2020 published by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, the doctor-patient ratio in rural India was approximately 1:10,926. The number of primary health centres was 31,494, indicating that the rural population has very limited access to hospitals, clinics and doctors, and a lot more still needs to be done around primary healthcare which is most fundamental to health.

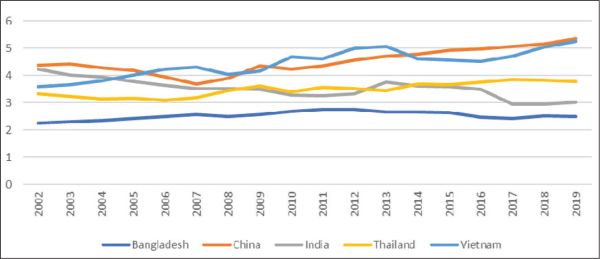

Irrespective of the fact that healthcare is a fundamental right under Article 21 of the constitution, the government spends just 1.5% of its GDP on healthcare (Sarwal & Kumar, 2021), while the world average is 6%, making the sector underserved and leaving it for the private sector to take over major services. Figure 1 clearly indicates India’s low thrust on healthcare.

Figure 1 indicates that India’s health expenditure is not only lower than other countries but has also declined over the years. Even among the BRIC countries, India’s healthcare spending has been the lowest for the year 2019 (OECD, 2019). A study analysing historical trends in healthcare spending by BRIC countries predicts the following trends for 2030: Brazil, 8.4% (95% PI 7.5, 9.4); Russia, 5.2% (95% PI 4.5, 5.9); India, 3.5% (95% PI 2.9%, 4.1%); China, 5.9% (95% PI 4.9, 7.0); South Africa, 10.4% (95% PI 5.5, 15.3) (Jakovljevic et al., 2022). The out-of-pocket expenditure on health in India continues to be significant. Though the figures have reduced from 69.4% in 2004–2005 to 48.31% in 2018–2019, it is still high, as per the National Health Accounts. According to the statistical reports for India and China, 37 and 32 million people, respectively, are under the poverty line due to OOP payment, and this results in the risk of pushing people into financial disaster and poverty.

Figure 1. Health Expenditure as a Share of GDP Across Countries.

Note: For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure, please refer to the web version of the article.

Over the last two decades, health-tech start-ups have also attempted to crack the archaic healthcare system. Start-ups bring in novel ideas and methods to improve the accessibility and affordability of healthcare. However, one of the major challenges that they face in this space is that they are generally capital-demanding and have comparatively slower returns, particularly in minor locations. Under such circumstances, very few start-ups can survive despite the lower competition levels. Another challenge for the health start-ups is the lack of health data, which is fragmented as of the date, and the fact that the healthcare industry has not been that agile in adopting new technologies for accessibility to health data. Likewise, because health start-ups have prolonged gestation periods, venture capitalists invest in companies that are able to make money in five to seven years, with most avoiding healthcare funding due to this reason.

Another hurdle in India’s healthcare system is compliance and regulatory factors. While there have been efforts to simplify and streamline the regulatory framework, there are still challenges in implementing and enforcing policies effectively, possibly due to presence of multiple regulators, enforcement challenges and standardisation challenges. In addition, some of the laws governing this space are so aged and need to be changed under existing circumstances. The Drug and Cosmetics Act 1940, Drugs and Cosmetic Rules 1945, Pharmacy Act 1948 and Indian Medical Act 1956 were crafted way before the age of e-commerce. The Information Technology Act 2000 still lies in the grey area when it comes to healthcare technology. The policies are mostly unclear vis-à-vis the current scenario, leading to ambiguity and the reluctance of healthcare practitioners and players partnering with start-ups. As far as healthcare devices go, it is ironic that despite the hyped ‘Make in India’ campaign, foreign players dominate the market.

Despite an overall increase in technology adoption, there are barriers to technology innovation in healthcare. Indian markets are not uniform, and behaviour of consumers changes after a radius of 30–50 km, creating obstructions to building business or market strategies for new products and services. Healthcare innovators often find it hard to scale due to a fractured market and gradually fall out (Dr. Hempel Digital Health Network, 2018). While consumers who are exponentially adopting technology for e-commerce, social media, education and the like are awry of doing the same when it comes to their health. More so, the working and operating styles of healthcare professionals and healthcare centres are also uneven with most having their own unique practices, making things more difficult to standardise.

Rethinking Healthcare: An Integrated Approach

A country’s ailing health system has a negative impact on its productivity and economic output. India cannot accomplish its growth potential without a robust healthcare system, for which an integrated healthcare approach needs to be adopted. There is good evidence to show that health systems which are end-to-end consolidated and connect people’s patterns of health through their life cycles have far better health consequences (Levine et al., 2019; Starfield et al., 2005) for the same level of expenditure than those that leave people to handle their own health until they are truly sick, post which they follow the hospital-based approach (Mor, 2019). Countries that have highly effective health systems, like the United Kingdom (Cylus et al., 2015) in the developed world, Thailand (Tangcharoensathien, 2015) and Costa Rica (Pesec et al., 2017) in the developing world, have been able to have fruitful impacts to offer.

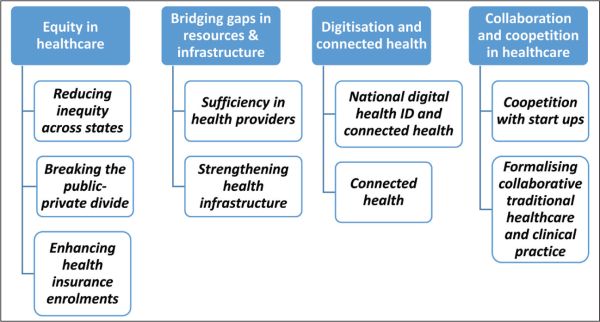

It is, therefore, clear that fragmented or patchwork efforts will not help; rather, we have to consciously invest in our health systems to not only make them stronger and safer but also interconnected. What we need is an integrated approach to strengthening our infrastructure and resources and linking and empowering all stakeholders in the healthcare ecosystem for overall enhancement in healthcare, uniformly, transparently and equally. Keeping this in mind, we present and explain in Figure 2 an integrated approach to tackle challenges in healthcare by strengthening the bond between the healthcare provider, receiver and environment, thus moving from a reactive to a proactive approach in healthcare.

Figure 2. An Integrative Framework.

Equity in Healthcare

Reducing Inequity Across States

Equity in health is as important as social and economic equity. In India, presently, health is primarily a state subject, due to which there are huge variations and inequality in healthcare facilities, accessibility and infrastructure across the country as states have skewed priorities. The fragmented health infrastructure is largely due to the way in which roles and responsibilities have been framed between the centre and the states. To take an example, the centre spends less on public health and sanitation as they are on the state list. To bring parity across states in terms of healthcare facilities, policies and infrastructure, the centre has to redefine responsibilities and ownership by either taking health directly into their focus or putting in place a central monitoring mechanism that constantly views and reviews every state’s healthcare systems. With the rise of e-healthcare, it is imperative to have a central regulatory framework rather than multiple frameworks, along with clear privacy guidelines and enforcement, to provide affordable, accessible and quality healthcare across India.

Breaking the Public–Private Divide

In addition to addressing the existing inequities across states, it is crucial for the centre to also tackle the public-private divide in healthcare. The lack of health data integration between the public and private sectors, and the scarcity and inadequate quality of public infrastructure force individuals to seek medical care at private hospitals, even if they cannot afford the expenses. This places an enormous burden on people’s already limited financial resources. According to the National Family Health Survey-3, 70% of households in urban areas and 63% of households in rural areas depend on the private medical sector as their primary source of health. The huge burden of out-of-pocket expenditure to the tune of approximately 65% to 70% also increases the possibility of vulnerable groups slipping into poverty. Accessibility and quality of public health facilities are, therefore, imperative to counter this situation. An increase in the proportion of GDP spent on healthcare can definitely help enhance the Public Health Infrastructure and also decrease the OOPE, thus reducing the financial strain on the endangered groups.

Enhancing Health Insurance Enrolments

India is a country with one of the lowest health insurance penetration rates. Around 65% of India’s population is not covered under any health insurance plan (Statista, 2022). The government needs to play a strong role in the adoption of health insurance plans by a larger section of society. Private health insurance plans target people in the higher income category, and therefore the government needs to devise a significantly low-cost health insurance product covering outpatient-care that will help rope in people with lesser incomes who have the capacity to pay nominal insurance.

Though the Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana is a step towards offering accidental death and disability benefits to policyholders, and though health insurance coverage has also shown an upward trend over the last five years, according to the latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), it still remains well below half the population in most of the states. Of the 22 states gauged, 15 states demonstrated increased in health coverage, but other than Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Assam and Kerala, all major states indicated less than 50% of households with one member covered by a health scheme. Healthcare financing is core to progressing towards universal health coverage, and the government of India could weigh the World Health Organization (WHO) approach of considering the four key financing strategies to achieve UHC—increasing taxation efficiency, increasing government budgets for health, innovation in financing for health and increasing development assistance for health.

Bridging Gaps in Resources and Infrastructure

Sufficiency in Health Providers

First and foremost, we cannot achieve good health systems and standards if we do not have adequate and trained medical professionals. It is estimated that by 2030, India will need 2.07 million more doctors to achieve the doctor-to-population ratio of 1:1000 as set by WHO (Tiwari et al., 2018). The states with higher deficit of doctors, like Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha and Madhya Pradesh, are home to a big chunk of India’s rural population of more than 0.8 billion (Parvathi & Loni, 2022). It is also important for India to ensure that the shortage of medical staff is addressed in rural areas, as primary healthcare is the foundation of public health services in a country. The importance of primary care can be seen from the evidence congregated by the World Bank that 90% of healthcare needs can be managed by primary care, while only 10% require services supplemented by hospitals (Rao & Pilot, 2014).

It may be pertinent to point out that we need to look at novel and unique ways of enhancing the availability of skilled hands in the healthcare sector. In addition to the regular route of attracting and retaining talent in healthcare, the other options worth considering will be scrutinising how the existing medical workforce is deployed and how it can be reallocated for better productivity. Interstate licence compacts for multi-state practice or having medical colleges attached to all major government hospitals will also increase the availability of a medically trained workforce under emergency circumstances. Efforts around creating a pool of contingency staff for deployment on a need-based basis with constant evaluation and monitoring with a ‘do not return’ tag for those who are found misfits or not suitable may also be another way of resourcing medical staff.

Strengthening Health Infrastructure

The pandemic has clearly shown India’s lack of infrastructure to cater to its 1.38 billion population. There are no two opinions on the fact that healthcare infrastructure needs deep-rooted and massive reforms to make it strong enough to face crises of unprecedented magnitude. Breaking the vicious cycle of poverty and poor health is indispensable for economic development and growth. Achieving better health for a nation requires the transformation in not only the health sector but beyond it too. Within the health sector, the focus should encompass basics like education, sanitation, health awareness and targeted measures to support vulnerable groups. Additionally, efforts should extend to more advanced aspects like building research capacities, enhancing medical staff and resources, upgrading supply and distribution chain, mobilising additional resources from public-private partnerships, domestic and philanthropic initiatives.

Rural India severely lacks adequate health infrastructure, and what does exist does not meet adequate quality requirements, is underfinanced, has poor equipment, a low supply of medicines and lacks qualified and dedicated human resources. Additionally, the underdeveloped state of roads and railways as well as the issue of erratic power supply make it even more difficult to set up rural health facilities. It is essential that these issues be prioritized and addressed urgently to ensure the provision of adequate healthcare services in rural areas.

Digitisation and Connected Health

National Digital Health ID and Connected Health

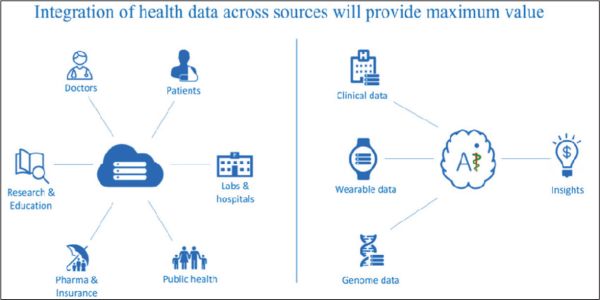

With the advances in information and communication technologies, India must work towards ‘connected health’ and open digital health ecosystem empowering information transparency, interoperability and innovation across stakeholders. For delivering quality health outcomes, data from multiple sources will aid better diagnosis, treatment and bring about a paradigm shift in the way healthcare is facilitated.

Presently, the healthcare stakeholders in India operate in silos, and the availability of health data is fragmented and broken. Patient life cycle health data will not only help health data flow seamlessly across healthcare receivers and providers but also reduce costs on account of repeated diagnostic tests, support disease diagnosis and treatment advised to patients, enhanced awareness, preventive and predictive health and remote patient treatment and monitoring, to name a few. With the advent of wearables, AI, ML and IoT, health data can immensely aid in changing the outlook from symptomatic treatment to preventive and predictive healthcare. Figure 3 indicates how health data from multiple sources can be collated and collectively studied for better diagnosis, prescription and treatment.

Figure 3. Future of Health Data: Connected Health.

What we need here is a two-pronged approach. First, every citizen of India needs to have a health identity. The government may decide to use the Adhaar number as an identity or generate an Adhaar-based health ID for every citizen. Gradually, those not having Adhaar should also be brought into this fold. There is a dire need for immediate implementation of the Unique Health Identifier Rules, 2021, which were notified on 1 January 2021, and which are meant to help facilitate the ‘integration of health data across various applications and create longitudinal Electronic Health Records for citizens’.

Second, all healthcare stakeholders like the patient and health providers like doctors, registered clinics, polyclinics, hospitals, government health centres, diagnostic services and pharmacies should be brought on a connected platform so that health data is easily accessed across the life-cycle of every citizen. Additionally, block chain can be used to ensure the safety, security and privacy of the data, with heavy punishment for misuse.

The implementation of a digital health ID and a connected platform would greatly facilitate the collation and tracking of patient data throughout their lifetimes. Such a system would enable seamless sharing of information with healthcare providers, hospitals, and insurance companies with just a click significantly enhancing the efficiency and accessibility of healthcare services. Numerous hospitals have adopted IT/EHR systems, but primarily for patient registration and not so much for clinical use. Prior to the pandemic, adoption of digital technology in healthcare was rather slow; however, post-pandemic demands for contactless consultation and medication have given a new thrust, and it looks like digital technology is now here to stay and evolve for the betterment of mankind.

Collaboration and Coopetition in Healthcare

Coopetition with Start-ups

Disruptive growth requires new business models. Entrepreneurs have the ability to identify complex problems and develop innovative, simple and efficient solutions for them. The pandemic has led to a structural shift towards digital healthcare in many countries, including India. Start-ups are a very effective way of promoting innovation, and the COVID-19 pandemic has forever changed how start-ups will do business in the future. We have seen start-ups as catalysts for innovation, be it in the areas of low-cost ventilators, chatbots to address queries, thermal cameras with an alerting system, contact tracing technologies, transportation for frontline workers, community-based platforms enabling lifestyle discovery and the like. Start-ups can also help tap the opportunities, bring in a viable business model and support the government in strengthening loopholes in the healthcare system.

Start-ups like Tattvan E Clinics, myUpchar, Portea Medicals, Practo, mFine, Lybrate, DocsApp and MedCords are a few among many others working towards not only strengthening the present infrastructure but also creating an ecosystem that will be seamless and accessible for all its stakeholders (Naik, 2020). Swasth Alliance is another example in which over 100 players in the health ecosystem, such as hospitals, health-tech start-ups, pharmacies, technology and other organisations, have collaborated to overcome some of the healthcare challenges. Collaboration and coopetition can therefore play a very critical role in building national capacities by rebooting healthcare and closing gaps in the traditional healthcare ecosystem.

Formalising Collaborative Traditional Healthcare and Clinical Practice

India has a very rich heritage of traditional forms of medicine like Ayurveda, Siddha, Unani and homeopathy, which largely use plant-based medications for promoting health and curing illness and have been used for centuries. India is among the largest producers of medicinal plants, and there are over 7.7 lakh registered ‘AYUSH doctors practicing in India (Ayurveda-428884 [55.4%], Unani-49566 [6.4%], Siddha-8505 [1.1%], Naturopathy-2242 [0.3%] and Homoeopathy-284471 [36.8%]; Shailaja & Kishor, 2018). Modern research has acknowledged the importance of traditional medicinal systems and their effectiveness. Japan’s Osaka Medical School has formed a society of Ayurveda way back in 1969 and has been passionately spreading Ayurveda forms of treatment. Ayurveda is also prevalent in Thailand and Myanmar, and education and practice of Ayurveda are thriving in many states of the USA (Sen & Chakraborty, 2017).

Research-backed and scientific integration or collaboration of Ayurvedic and other forms of Indian traditional medicine in clinical practice may help cure diseases in a more wholesome way with fewer side effects. Moreover, a large section of people who cannot afford expensive treatment can benefit from more reasonable forms of traditional medications if they are available in primary health centres. Treatment based on a combination of modern and traditional medicines can also be formalised as more and more people adopt traditional wellness and lifestyle methods.

Many foreign countries have shown interest in India’s ancient forms of health and wellness and are keen on collaborations for research and development. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Government of India have also agreed to establish the WHO Global Centre for Traditional Medicine to harness the potential of traditional medicine to better the health of people as well as the planet. India, being the origin of non-drug therapies and preventive and life management techniques, must utilise this precious resource for the well-being of its citizens.

Conclusion, Limitations and Way Forward

Going by the trends, there is a vast undercurrent in healthcare, and in the next few years, healthcare will be very different from how we see it today. India has a very fragile healthcare infrastructure that needs to be forcefully and vigorously strengthened. If India does not bring systemic changes in the healthcare system, the impact of the country’s economic growth might be negated. Beleaguered by a shortage of medical professionals, inadequate infrastructure, a lack of digitisation, poor technology adoption, a shortage of funds and high out-of-pocket expenditures, the situation is visibly a huge challenge for the country. Over the years, healthcare costs have skyrocketed, the quality of care is inconsistent and patient experience needs drastic improvements.

A thorough analysis of the gaping loopholes and the lessons learned, along with charting out a multipronged approach to fix the current system, is a dire need of the hour. Integrating and streamlining disparate systems and processes, strategic reforms by the government on existing inequities in healthcare, technology convergence and new healthcare delivery models will help bridge the existing gaps and play a vital role in improving accessibility, affordability, transparency and greater awareness for better quality systems in healthcare.

Since this article is from the perspective of the author, there are some limitations that need to be acknowledged. The author’s own understanding, analysis or interpretation may influence the arguments presented in the article. Although the perspective may be short of comprehensive, it is well known that, going forward, digital changes will empower all sectors, including healthcare. Integrating healthcare delivery with exponentially increasing data from genomics, the microbiome, imaging, digital health, environmental information and more will be a game changer. AI and digital platforms will churn around diagnostics and reduce misdiagnosis while pharmacy will evolve from a mere dispenser of medications to being a vital healthcare team member with a more clinical role in patient care. Pharmacists are likely to take on greater responsibilities in areas such as medication management, patient counselling and chronic disease management as the healthcare system in India evolves.

In every crisis lies an ocean of opportunities, and this is a good time to revisit old models, redefine them or create new ones. Having gone through the COVID crisis, each of us will surely agree to the age-old saying that ‘health is wealth’. The time cannot be more appropriate to take a deep dive into our healthcare system and bring in groundbreaking changes to democratise healthcare so that not only the nation but every citizen be able to take charge of their health for both self and national prosperity.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author of this study declare that the article neither has been published nor is/will be under consideration for publication elsewhere until the editorial decision from BIMTECH Business Perspectives has been communicated.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Cylus, J., Richardson, E., Findley, L., Longley, M., O’Neill, C., & Steel, D. (2015). United Kingdom: Health system review. Health Systems in Transition, 17(5), 1–126.

Dr. Hempel Digital Health Network. (2018, November). Challenges faced by digital health startups. Challenges in ehealth India. https://www.dr-hempel-network.com/digital-health-startups/challenges-in-ehealth-india/

Gopal, K. M. (2019). Strategies for ensuring quality health care in India: Experiences from the field. Indian Journal of Community Medicine: Official Publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine, 44(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_65_19

Howell, B. (2021). The countries who’ve handled coronavirus the best – and worst. Movehub.com. https://www.movehub.com/blog/best-and-worst-covid-responses/

Ibef.org. (2021). Indian healthcare industry analysis. https://www.ibef.org/industry/healthcare-presentation

Inc42.com. (2020). The annual Indian tech startup funding report 2020. https://inc42.com/infocus/startup-watchlist-2021/startup-watchlist-6-indian-healthtech-startups-to-watch-out-for-in-2021/

India: Health insurance penetration 2018. (2019, October 1). Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1080112/india-health-insurance-penetration/

Jakovljevic, M., Lamnisos, D., Westerman, R., Chattu, V. K., & Cerda, A. (2022). Future health spending forecast in leading emerging BRICS markets in 2030: Health policy implications. Health Research Policy and Systems, 20, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00822-5

Levine, S., Malone, E., Lekiachvili, A., & Briss, P. (2019). Health care industry insights: Why the use of preventive services is still low. Preventing Chronic Disease, 16, E30. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd16.180625

Martin, M., Lawson, M., Abdo, N., Waddock, D., & Walker, J. (2020). Fighting inequality in the time of COVID-19: The commitment to reducing inequality index 2020. Oxfam Development Finance International. https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/621061/rr-fighting-inequality-covid-19-cri-index-081020-summ-en.pdf

Mor, N. (2019). Lessons for developing countries from outlier country health systems. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.28638.18244

Naik, A. R. (2020). NDHM eases healthcare data hurdles, but can startups bridge infrastructure gaps? Inc42.com. https://inc42.com/features/ndhm-fixes-healthcare-data-but-can-startups-bridge-infrastructure-gaps/

OECD. (2019). Health at a glance 2019: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/4dd50c09-en.

Parvathi B., & Loni D. (2022, July 10). Rural India is struggling with shortage of doctors, paramedical staff. The Hindu Business Line: Business Financial, Economy, Market, Stock-News & Updates. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/data-stories/deepdive/rural-india-is-strugglingwith-shortage-of-doctors-paramedicalstaff/article65623110.ece

Pesec, M., Ratcliffe, H. L., Karlage, A., Hirschhorn, L. R., Gawande, A., & Bitton, A. (2017). Primary health care that works: The Costa Rican experience. Health Affairs, 36(3), 531–538. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1319

Rajagopalan, S., & Choutagunta, A., (2020). Assessing healthcare capacity in India [Mercatus Working Paper]. https://www.mercatus.org/research/working-papers/assessing-healthcare-capacity-india

Ranganathan, S. (2020, April). Towards a holistic digital health ecosystem in India [ORF Issue Brief No. 351]. Observer Research?Foundation. https://niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2021-3/InvestmentOpportunities_HealthcareSector_0.pdf

Rao, M., & Pilot, E. (2014). The missing link: The role of primary care in global health. Global Health Action, 7, 23693. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23693

Rekha, M. (2020). COVID-19: Health care system in India. Health Care: Current Reviews, (S1), 262. https://doi.org/10.35248/2375-4273.20.S1.262; https://www.walshmedicalmedia.com/open-access/covid19-health-care-system-in-india-58032.html

Sarwal, R., & Kumar, A. (2021). Health insurance for India’s missing middle (Preprint). Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/s2x8r

Sarwal, R., Prasad, U., Madangopal, K., Kalal, S., Kaur, D., Kumar, A., Regy, P. & Sharma, J. (2021, March). Investment opportunities in India’s healthcare sector. NITI Aayog.

Sen, S., & Chakraborty, R. (2017). Revival, modernization and integration of Indian traditional herbal medicine in clinical practice: Importance, challenges and future. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, 7(2), 234–244.

Shailaja, C., & Kishor, P. (2018). Allopathic, AYUSH and informal medical practitioners in rural India: A prescription for change. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine, 9(2), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaim.2018.05.001

Starfield, B., Shi, L., & Macinko, J. (2005). Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. The Milbank Quarterly, 83(3), 457–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1468-0009.2005.00409.x

Tangcharoensathien, V. (Ed.). (2015). The Kingdom of Thailand health system review. Health Systems in Transition, 5(5). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/208216

Tiwari, R., Negandhi, H., & Zodpey, S. P. (2018). Health management workforce for India in 2030. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 227. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00227