1 Brainware University, Barasat, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Social media influencers also identified as micro-celebrities commonly entitled influencers, who provide content or thoughts based on their ideas and present experiences and ideas in the form of content or opinions. They are gaining popularity in the world of brand endorsement for attracting, developing and retaining consumers for their financial gain. The key emphasis of this study is to comprehend what motivates an individual to follow an influencer on social media platforms, so that the companies can efficaciously choose a social media influencer for their brand endorsement. Specifically, the major purpose of this study was to explore why an individual follows an influencer, so company can choose an influencer effectively. To achieve these aims, we choose to use questionnaires for an online survey among the social media users who follow at least one influencer, the questionnaire was circulated through social media and email. 392 individuals above 16 years old filled out the questionnaire. The outcome of the study confirmed that there are seven primary factors that motivate the social media audience to follow their selected influencers, namely authenticity, trustworthiness, attractiveness, credibility, expertise, legitimacy and likeability. The key takeaway from the study is that marketers, influencers and advertising agencies will be able to understand what factors affect the social media audience’s intention to follow the influencers. This study will make theoretical as well as practical contributions for the marketers as well as the influencers to understand what influences the users’ intention to follow social media influencers.

Social media, influencer, followers, audience, intention to follow

Introduction

A social media (SM) influencer (hereafter, ‘influencer’) also known as ‘a content generator, one who has a status of expertise in a specific area, who cultivated a sizable number of captive followers—those are of marketing value to brands—by regularly producing valuable content via social media’ (Lou & Yuan, 2019, p. 59). The SM influencers are also known as micro-celebrities, digital celebrities and micro-influencers, but commonly they are called influencers, who reshape the attitudes of their SM audience (Freberg et al., 2011). Thus, they establish close relationships with the audience and maintain the relationship over time (De Veirman et al., 2017; Jin & Ryu, 2020; Tafesse & Wood, 2021). According to Hu et al. (2020), Schouten et al. (2021) and Tafesse and Wood (2021), the influencers are recognised for their SM activity. In contrast, traditional celebrities are recognised for their non-SM–related activities (e.g., cinema, sports and music). Due to their credibility status (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020; Stubb et al., 2019), expertise (Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017; Stubb et al., 2019) and effective communication (Jiménez-Castillo & Sánchez-Fernández, 2019), they are followed by the SM audience. De Veirman et al. (2017) are viewed as attractive, trustworthy, likeable and trustworthy sources of information and effective spokespersons (Fink et al., 2004). Hence, for developing strong and long-lasting relationships, they interact regularly (Sokolova & Perez, 2021) with their followers and create their communities (Tafesse & Wood, 2021).

Prior research shows that social influencers are effective for endorsements (Agnihotri & Bhattacharya, 2021; Gräve & Bartsch, 2022; Schouten, et al., 2021; Weismueller, et al., 2020). Although there are several studies on the effect of SN influencers on consumer engagement and purchase intention, there is a dearth of comprehensive studies on factors influencing individual to follow the SM influencers. Further, prior researchers have deliberated on the influence of perceived information quality and trustworthiness of the influencer on attitude towards influencers (Balaban et al., 2020), authenticity, consumerism, creative inspiration and envy are the driving forces behind following an influencer on Instagram are (Lee et al., 2022); still, it remains unclear what are factors motivate one to follow an influencer. Based on the prior research seven factors were identified for further study. Additionally, it is critical to comprehend the elements that contribute to the growth of a para-social relationship, in which followers see influencers as friends—between followers and influencers (Labrecque, 2014). Therefore, by investigating the variables influencing a person’s prosperity to follow an influencer, this research aims to close the gap in the literature. De Veirman et al. (2017) mentioned that marketers are struggling to identify the influencers that suit their promotional activities or their products. Prior research has established that the acceptability of an influencer plays an important role in inspiring the followers to purchase a product (Chan, 2022; Hughes, et al., 2019). A variety of evaluation metrics, including followers, likes, comments, credibility and potential audiences, have been employed in the past to analyse influencers (Choi & Rifon, 2012; Freberg et al., 2011; Jabr & Zheng, 2022; Lee & Koo, 2012). However, the investigation of factors influencing the audience’s intention to follow an SM influencer in emerging countries is still limited. Therefore, this article made an effort to find out the factors that influence an audience’s intention to follow an SM influencer. This study will help marketers to know the factors influencing audience behaviour, and it will permit them to develop better to choose influencers more effectively for attracting the target audience towards them. Based on the prior research, this article proposes to identify the factors affecting audience’ intention to follow an influencer. The research question for the study:

RQ: What are the key factors that influence the audience’s intention to follow an influencer?

This research will help marketers by providing valuable insight into how to evaluate an influencer and select a suitable influencer for advertisement. This article is organised as follows: The second section covers the literature review and describes the concept of SM influencers, and the theoretical foundation and research framework; the third section consists of the research methodology used in the research. Then, the fourth and fifth sections cover findings and discussion, respectively. The sixth section presents implication and conclusion. The seventh section presents limitations and future direction.

Literature Review

Social Media Influencers

SM influencers generate electric word of mouth (eWOM) by providing content on one or more SM platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat or personal blogs (Chen & Yuan, 2018; Freberg et al., 2011). They influence SM audiences to a certain extent by sharing their knowledge, skills and recommendations (Bognar et al., 2019; De Veirman et al., 2017) and behaviours (Byrne et al., 2017). The major objective of the influencers is to expand their communities by increasing the number of followers (Campbell & Farrell, 2020). They play a significant role in spreading news, popularising new trends (Jin et al., 2019), brands (Boerman et al., 2015; Wojdynski & Evans, 2016). Beyond advertisement, they are also involved in sending messages on environmental, social and political issues. They can be divided into three categories based on their impact, audience engagement and reach: mega-influencers, macro-influencers and micro-influencers.

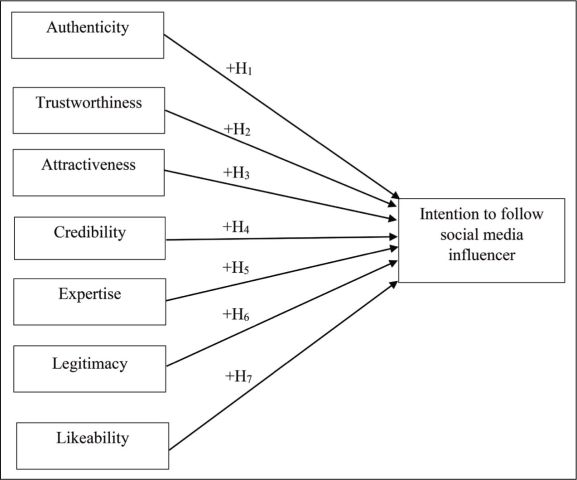

Unlike traditional celebrities, who gained their notoriety before using SM, influencers gained notoriety by creating content on SM platforms (Chae, 2017; Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017; Khamis et al., 2017). They also differ in how they interact with their followers, through online blogging and vlogging on SM platforms like Instagram, Twitter and YouTube, they are able to forge close and meaningful bonds with their followers (Hwang & Zhang, 2018; Jin & Phua, 2014). The influencers normally follow bidirectional relations, whereas traditional celebrities interact with their fans with the least personal touch (Chae, 2017; Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017; Khamis et al., 2017). This article develops a research framework to study the audience’s intention to follow an SM influencer. The underlying research framework is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Research Framework of the Study.

Research Framework

Intention to Follow

Behavioural intention refers to an individual willingness to perform particular behaviours (Ajzen, 1991). Casaló et al. (2017) mentioned that there is a linkage between behavioural intentions with actual behaviours. The present study examines the audience’s intention to follow an influencer by following his/her account, comments and opinion in SM or imitating an influencer which involves bringing their message into practice (Casaló et al., 2020), recommendations (Ki & Kim, 2019; Thakur et al., 2016), recommendation made by the influencers (Casaló et al., 2020). The followers may be with the followers (Casaló et al., 2017). Hence, the present study will examine the role of authenticity, trustworthiness, attractiveness, credibility, expertise, legitimacy and likeability in influencing the audience’s intention to follow an SM influencer.

Authenticity

Authenticity consists of external expressions and internal values and beliefs that lead to the growth of influencer–follower engagement. Taylor (1991, p. 17) defined authenticity as ‘that which is believed or accepted to be genuine or real’. Three points of view were merged by Morhart et al. (2015) to define authenticity as the extent to which customers are true to their brand, believe it and support their identity. Authenticity, then, is the extent to which followers perceive an influencer to be true to themselves, dependable, accountable and supportive of them. The degree of authenticity exhibited by influencers influences followers’ intentions to follow them directly and indirectly. The authenticity of the influencers has a direct impact on intention to follow and an indirect effect on the involvement of the followers. The audience looks for reliable opinions that they can trust. So, an influencer must exhibit a certain level of consistent values and behaviour towards the followers, so that they can respond positively. Conversely, unauthentic actions lead to public backlash (Tafesse & Wood, 2021). Authenticity helps influencers distinguish themselves from traditional celebrities, who usually keep their distance from their audience by forming hierarchical relationships based on carefully constructed fantasies (Duffy, 2017; cited in Cotter, 2019). Hence, the influencer-generated content allows them to develop intimacy and relatability with their followers and helps in developing effective relationships (Duffy, 2017; Marwick, 2013, 2015; cited in Cotter, 2019, p. 897). Accordingly, it is proposed that the authenticity of influencers will help to build strong relationships with their followers. Based on these, the following hypothesis is deduced:

H1: The authenticity of an influencer positively affects followers’ intention to follow him/her.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness denotes ‘the honesty, integrity and believability the endorser possesses’ (Van der Waldt et al., 2009, p. 104). It refers to the eagerness of an influencer to make lawful statements from any perspective and gain the truth of the followers (McCracken, 1989; Ohanian, 1990). The trustworthiness of an influencer demarcates the willingness of a follower to trust the influencer in someone they have confidence (Chen et al., 2019). According to O’Mahony and Meenaghan (1997), it impacts the followers and makes changes in their nature. Without gaining the trust of the followers, one cannot change the viewpoints of the followers (Miller & Basehart, 1969). Chao et al. (2015) and Wei and Li (2013) established that an influencer is trustworthy, they will influence the followers’ intention to follow. A positive association happens between the influencers and followers, if the content and opinions are trustworthy and fascinating. Prior research has established that audiences may trust influencers as much as they trust their friends (Chen & Yuan, 2019). The public tends to trust influencer posts compared to brand posts (Johnson et al., 2019). Thus, the trustworthiness of an influencer can help in developing strong relationships with their followers. On the basis of the assumptions, the following hypothesis is inferred:

H2: The trustworthiness of an influencer positively affects followers’ intention to follow him/her.

Attractiveness

Erdogan (1999, p. 299) specified that attractiveness is ‘a stereotype of positive associations to a person and entails not only physical attractiveness but also other characteristics such as personality and athletic ability’. Thus, an influencer who is more attractive will be followed more. The attractiveness of the influencers depends on the valuable messages, and opinions they share on SM (Wang & Scheinbaum, 2018). Further, Lou and Yuan (2019) mentioned that influencers’ attractiveness shapes the followers’ trust in the content. Influencer’s attractiveness basically depends on their similarity, familiarity and likeability to the followers (McGuire, 1985; Ohanian, 1991). Similarity refers to semblance between the followers and influencers, while familiarity refers to the expertise of the influencers and likeability refers physical beauty and behaviour of the influencers (McGuire, 1985). Thus, the attractiveness of an influencer may lead to a strong relationship with the follower. Accordingly, the proposed hypothesis:

H3: The attractiveness of an influencer positively affects followers’ intention to follow him/her.

Credibility

Erdem and Swait (2004) state credibility as the believability of something, which requires the audience to perceive that the person has the ability (i.e., expertise) to deliver the promise. An influencer can build credibility through authenticity (Hayes et al., 2007), transparency (Hayes et al., 2007) and trustworthiness (Hovland et al., 1953; Ohanian, 1990). Furthermore, the credibility of an influencer highly depends on his/her unbiasedness, believability, trustworthiness or factual recommendations (Hass, 1981). When the influencer is transparent with their audience to build trust, they are considered to be more credible. The followers’ desire to follow the updates and the posts on their blogs is influenced by the influencer’s credibility (Cosenza et al., 2015). Some influencers use branded products in their everyday lives to build strong credibility among their followers (Abidin & Ots, 2016) and project themselves as content to use (McQuarrie et al., 2012). An influencer is considered to be credible if they are perceived to be worthy by the followers. Thus, the credibility of an influencer determines the followers’ intentions to follow (Argyris et al., 2021; Cosenza et al., 2015; Schouten et al., 2021). Consequently, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H4: The credibility of an influencer positively affects followers’ intention to follow him/her.

Expertise

Expertise denotes ‘the degree to which the endorser is perceived to have the adequate knowledge, experience or skills to promote the product’ (Van der Waldt et al., 2009, p. 104). The people who are more informed about the topics when share their expert opinion will have a significant impact (Ratten & Tajeddini, 2017; Serazio, 2015). Expertise is a key attribute of an influencer which makes them successful, recognised and followed by the audience (Daneshvary & Schwer, 2000). An influencer is considered to be an expert in a field when followers believe in his/her skill, proficiency and knowledge (Schouten et al., 2019). Since the influencers play a significant role in elevating the skill sets of the followers, their messages and opinions have a significant effect on the audience (Balog et al., 2008). Therefore, the audience will tend to follow an influencer with an expertise skill sets. Thus, the proposed hypothesis:

H5: The expertise of an influencer positively affects followers’ intention to follow him/her.

Legitimacy

Legitimacy aids in overcoming the risk associated with newness. Prior researchers have mentioned that legitimacy helps in developing status, acceptance and reputation (Dibrell et al., 2009; Shepherd & Zacharackis, 2003). Legitimacy could be cognitive, regulative and normative legitimacy (Wang et al., 2014). Cognitive legitimacy is all about knowledge and belief in newness (Shepherd & Zacharackis, 2003; Wang et al., 2014), determined by the level of public awareness, which can be neutral, positive or negative about the phenomenon (Shepherd & Zacharackis, 2003). While regulatory legitimacy is derived from standards, rules, regulations and expectations created by the phenomenon (Wang et al., 2014; Zimmerman & Zeitz, 2002). According to Zimmerman and Zeitz (2002), acquiring regulative legitimacy leads to positive recognition. Normative legitimacy is an outcome of norms and values (Wang et al., 2014). The norms and values are acceptable by society (Wang et al., 2014). Thus, an influencer’s legitimacy may lead to acceptance of an influencer. Attaining these three forms of legitimacy will enable an influencer to influence their audience more effectively and efficiently (Dibrell et al., 2009). As it guarantees constancy, reliability and dependability (Dibrell et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2014), an audience will tend to follow an influencer with strong legitimacy. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H6: The legitimacy of an influencer positively affects followers’ intention to follow him/her.

Likeability

An influencer’s likeability is determined by how amiable, kind and enjoyable they are to be around (Doney & Cannon, 1997; Ellegaard, 2012; Tellefsen & Thomas, 2005). Thus, an influencer having likeable characteristics are more likely to be followed by the audience. Likeability often leads to positive association between influencers and followers; it is different from concepts of resemblance and attractiveness. According to Doney and Cannon (1997), likeability affects an individual’s confidence in predicting a companion’s upcoming behaviour. Although the prior research infers that likeability affects relationships, it is unclear how the idea of likeability affects the follower’s intention to behave. According to Tellefsen and Thomas (2005), likeability has strong relation towards commitment, physical appearance, behaviour and other characteristics (McGuire, 1985) and self-presentation (Cialdini, 2009) of a person. Thus, likeability is an important trait of an influencer which can influence the followers. Hence, on the basis of the assumption, this research proposed the following hypothesis:

H7: The likeability of an influencer positively affects followers’ intention to follow him/her.

Research Methods

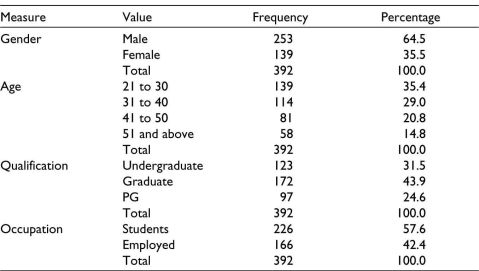

The research model was developed after a thorough literature review. However, there is hardly any study on the factors affecting audience intention to follow an influencer which has been used for understanding the audience behavioural intention in the field of SM marketing. So, for the present study, seven constructs were used for developing the research model for studying the connection between variables that are independent and dependent. A set of standardised questions was used to perform the survey. The screening question in the questionnaire’s introduction asked if the respondent had followed any SM influencers in the previous month. As a result, the initial question assisted in obtaining information exclusively from an SM influencer’s real followers. Thus, the introductory inquiry helps to gather data for actual followers of an SM influencer. Further, the statements for measuring independent and dependent variables were adopted as follows: authenticity (Moulard et al., 2015, 2016), trustworthiness (Ohanian, 1991), attractiveness (Ohanian, 1991), credibility (Wathen & Burkell, 2002), expertise (Ohanian, 1991), legitimacy (Van der Toorn et al., 2011), likeability (Doney & Cannon, 1997; Harnish et al., 1990) and intention to follow (Casaló et al., 2011). The questionnaire includes statements in all. All of the statements have been previously in various situations, and the questions have been improved to make the questionnaire more contextual. Every questionnaire item was scored using a five-point Likert scale, with one denoting ‘strongly agree’ to five denoting ‘strongly disagree’. Information of 392 respondents was obtained through online survey methods using Google Forms, as shown in Table 1. In addition, only a limited amount of demographic information, including gender, age, educational background and occupation, was requested of the respondents in order to protect their identity. SPSS and AMOS software are used in this study’s data analysis procedure.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Respondents’ Characteristics.

Findings and Discussion

Evaluation of the Measurement Model

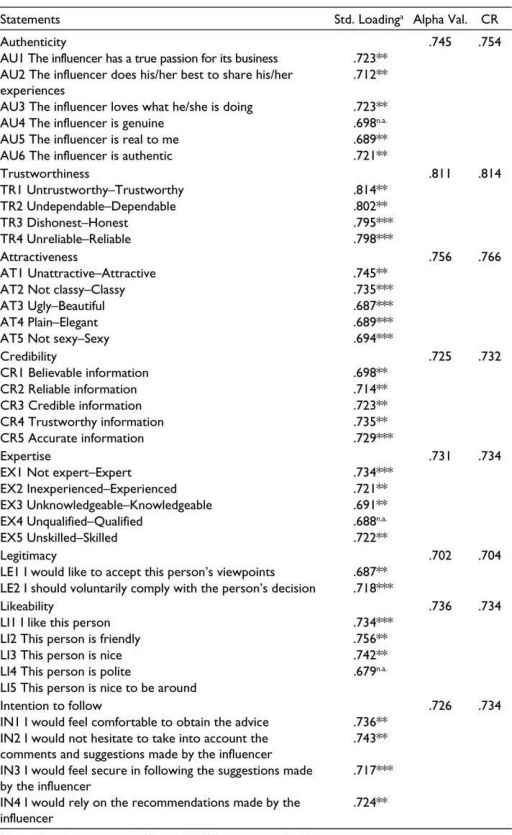

Research frameworks have been proposed using structural equation modelling (SEM) and confirmatory factor analysis. Convergent, discriminant, reliable validity results ensured that all of the study continued. Table 2 shows that all of the constructs’ Cronbach alpha values are over the 0.7 cut-off point (Hair et al., 2015), and composite reliability measure, which gauges the constructs’ internal consistency, also shows positive values (?.7 for each construct; Hair et al., 2015).

Table 2. Reliability Measures.

Note: aSignificant at p ? .05**, p ? .001***; n.a., not applicable.

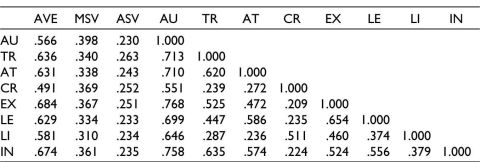

The correlation matrix, validity measures and convergent are shown in Table 3. The convergent validity of the items inside a concept was ensured by the values of AVE being larger than .5, and the discriminant validity among the constructs was implied by MSV and ASV values being smaller than AVE.

Table 3. Measures of Validity and Correlation Matrix.

Value for the variance inflation factor (VIF) was obtained for every construct. As the VIF values fell below the two-point threshold, ranging from 1.76 to 1.87, there is no problem with multicollinearity. Additionally, Table 4 shows the estimations from the measurement models, which fell within the desired limit that Hair et al. (2015) advised.

Table 4. Measurement Model Estimates.

Evaluation of the Structural Model

Establishing the Model Fit

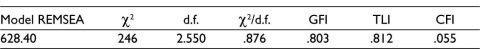

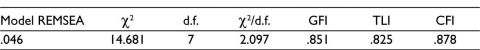

SEM was used to determine the associations between the dependent variable, IN and seven independent variables, AU, TR, AT, CR, EX, LE and LI, using AMOS21. As all of the indices fell within the designated ranges, Table 5’s results from a second-order analysis of the structural model indicate a strong model fit.

Table 5. Structural Model Estimates.

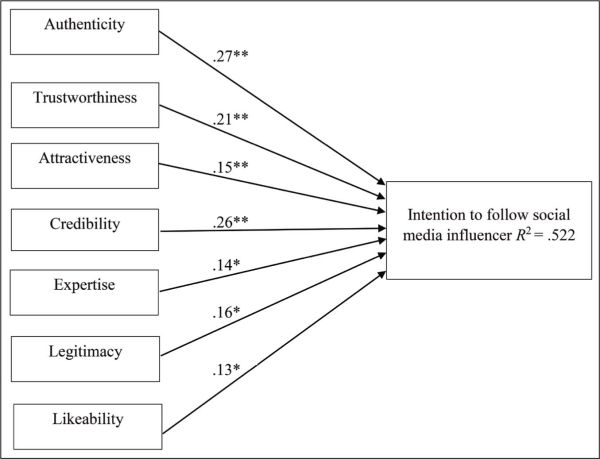

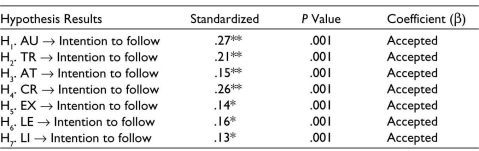

Hypothesis Testing

Testing the proposed theoretical relationships came next when the model fit was achieved. Figure 2 shows the structural model with standardised regression weight. The outcome is shown in Table 6. Each variable has a considerable impact on the audience and followers’ inclination to follow them. All seven of the study’s hypotheses have, in total, been accepted. Figure 2 demonstrates that all dependent variables are included in the suggested study framework and have a 52.2% (R2 =.522) explanatory power.

Figure 2. Research Model.

Table 6. Result of Hypothesis Testing.

Note: Significant at p < .001***, p < .05**, p < .01*.

Conclusion and Implications

In the existing study, we have explored that all these together AU, TR, AT, CR, EX, LE and LI add up to the reputation of an influencer and the audience intention to follow an SM influencer on WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and so on. The results show that AU, CR and TR are the attributes which contribute strongly to the popularity of the influencer, so the influencers should focus more on AU, CR and TR to gain increasing popularity and gain more endorsement deals in the future. Further, the result of this study reveals that authenticity is the strongest predictor which influences the audience’s behavioural intention to the followers which is in line with Lee et al. (2022), followed by credibility (Belanche et al., 2021), and trustworthiness (Balaban, et al., 2020). While legitimacy, attractiveness, expertise and likeability are less effective, the present study reveals a positive but weak relationship between legitimacy, attractiveness, expertise and likeability with the intention to follow the SM influencer may be because the followers feel that influencers can easily attain and exercise these features.

The present study identified seven important dimensions which affect the SM followers’ intention to follow an influencer. The findings of the study revealed that the model was able to explain 52.2% of the variance towards behavioural intention. The study established that marketers should give the most importance to the authenticity of an influencer. They should also give high priority to the credibility and trustworthiness of an influencer before selecting them for brand endorsement or publicity. Moreover, current research emphasised an influencer’s authenticity credibility, trustworthiness, legitimacy, attractiveness, expertise and likeability that help the marketers to promote their brands and penetrate a large and more focused market segment through the influencers.

Occasionally, marketers place a great deal of blind trust in influencers to market and increase sales of their goods and services. Occasionally, they may tend to overestimate the influential power of an influencer. So, this study will be helpful for the marketers in future in selecting an influencer. The influencers will develop these attributes to grow and retain their popularity and remain beneficial.

Limitation and Future Research

It is necessary to address certain limitations with regard to the present study’s generalisation. First, the study is restricted to India; it would be better to see the suggested model replicated in other emerging nations as well as possibly in other developed nations. Second, the intention to follow an influencer seems to be beneficial for the marketers as well as the influencers for the decision-making. The current research did not consider any factor which may act as a barrier and affect the behavioural intention to the follow an SM influencer negatively. Third, the researcher may consider different apps separately to make it more beneficial for them in the future. Finally, researchers in the future may compare the behavioural intentions of followers toward SM influencers through longitudinal studies. Potential avenues for further research include incorporating additional variables that impact an audience’s inclination to follow an influencer.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Piali Haldar  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4729-6964

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4729-6964

Abidin, C., & Ots, M. (2016). Influencers tell all: Unravelling authenticity and credibility in a brand scandal. In M. Edström, A. T. Kenyon, & E.-M. Svensson (Eds.), Blurring the lines: Market-driven and democracy-driven freedom of expression (pp. 153–161). Göteborg.

Agnihotri, A., & Bhattacharya, S. (2021). Endorsement effectiveness of celebrities versus social media influencers in the materialistic cultural environment of India. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 33(3), 280–302.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Argyris, Y. A., Muqaddam, A., & Miller, S. (2021). The effects of the visual presentation of an influencer’s extroversion on perceived credibility and purchase intentions: Moderated by personality matching with the audience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59, 102347.

Balaban, D., Iancu, I., Must?t,ea, M., Pavelea, A., & Culic, L. (2020). What determines young people to follow influencers? The role of perceived information quality and trustworthiness on users’ following intentions. Romanian Journal of Communication and Public Relations, 22(3), 5–19.

Balog, K., Rijke, M. D., & Weerkamp, W. (2008). Bloggers as experts: Feed distillation using expert retrieving models. In S. H. Myaeng, D.W. Oard, F. Sebastiani, T.-S. Chua, & M.-K. Leong (Eds.), Proceedings of the 31st annual international ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in information retrieval (pp. 753–754). ACM.

Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., Flavián, M., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2021). Building influencers’ credibility on Instagram: Effects on followers’ attitudes and behavioral responses toward the influencer. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61(4), 102585.

Boerman, S. C., van Reijmersdal, E. A., & Neijens, P. C. (2015). How audience and disclosure characteristics influence the memory of sponsorship disclosures. International Journal of Advertising, 34(4), 576–592.

Bognar, Z. B., Puljic, N. P., & Kadezabek, D. (2019). Impact of influencer marketing on consumer behaviour. Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings, pp. 301–309.

Byrne, E., Kearney, J., & MacEvilly, C. (2017). The role of influencer marketing and social influencers in public health. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 76(OCE3), E103.

Campbell, C., & Farrell, J. R. (2020). More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Business Horizons, 63(4), 469–479.

Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Guinalíu, M. (2011). Understanding the intention to follow the advice obtained in an online travel community. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 622–633.

Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2017). Antecedents of consumer intention to follow and recommend an Instagram account. Online Information Review, 41(7), 1046–1063.

Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2020). Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. Journal of Business Research, 117, 510–519.

Chae, J. (2017). Virtual makeover: Selfie-taking and social media use increase selfie-editing frequency through social comparison. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 370–376.

Chan, F. (2022). A study of social media influencers and impact on consumer buying behaviour in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Business & Management Studies, 3(07), 2694–1449.

Chao, P., Wuhrer, G., & Werani, T. (2015). Celebrity and foreign brand name as moderators of country-of-origin effects. International Journal of Advertising, 24(2), 173–192.

Chen, L., & Yuan, S. (2018). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73.

Chen, X., Yuan, Y., Lu, L., & Yang, J. (2019). A multidimensional trust evaluation framework for online social networks based on machine learning. IEEE Access, 7, 175499–175513.

Choi, S. M., & Rifon, N. J. (2012). It is a match: The impact of congruence between celebrity image and consumer ideal self on endorsement effectiveness. Psychology & Marketing, 29(9), 639–650.

Cialdini, R. B. (2009). Influence: Science and practice (Vol. 4). Pearson Education.

Cosenza, M. N. (2015). Defining teacher leadership: Affirming the teacher leader model standards. Issues in Teacher Education, 24(2), 79–99.

Cosenza, T. R., Solomon, M. R., & Kwon, W-Suk (2015). Credibility in the blogosphere: A study of measurement and influence of wine blogs as an information source. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 14(2), 71–91.

Cotter, K. (2019). Playing the visibility game: How digital influencers and algorithms negotiate influence on Instagram. New Media & Society, 21(4), 895–913.

Daneshvary, R., & Schwer, R. K. (2000). The association endorsement and consumers’ intention to purchase. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 17(3), 203–213.

De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: the impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 36(5), 798–828.

Dibrell, C., Craig, J. B., Moores, K., Johnson, A. J., & Davis, P. S. (2009). Factors critical in overcoming the liability of newness: Highlighting the role of the family. The Journal of Private Equity, 2(12), 38–48.

Djafarova, E., & Rushworth, C. (2017). Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 1–7.

Doney, P. M., & Cannon, J. P. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer–seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 61(2), 35–51.

Duffy, B. E. (2017). (Not) getting paid to do what you love: Gender, social media, and aspirational work. Yale University Press.

Ellegaard, C. (2012). Interpersonal attraction in buyer–supplier relationships: A cyclical model rooted in social psychology. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(8), 1219–1227.

Erdem, T., & Swait, J. (2004). Brand credibility, brand consideration, and choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 191–198.

Erdogan, B. Z. (1999). Celebrity endorsement: A literature review. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(4), 291–314.

Fink, J. S., Cunningham, G. B., & Kensicki, L. J. (2004). Using athletes as endorsers to sell women’s sport: Attractiveness vs. expertise. Journal of Sport Management, 18(4), 350–367.

Freberg, K., Graham, K., McGaughey, K., & Freberg, L. A. (2011). Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relations Review, 37(1), 90–92.

Gräve, J. F., & Bartsch, F. (2022). #Instafame: Exploring the endorsement effectiveness of influencers compared to celebrities. International Journal of Advertising, 41(4), 591–622.

Hair, N. L., Hanson, J. L., Wolfe, B. L., & Pollak, S. D. (2015). Association of child poverty, brain development, and academic achievement. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(9), 822–829.

Harnish, R. J., Abbey, A., & DeBono, K. G. (1990). Toward an understanding of ‘the sex game;: The effects of gender and self-monitoring on perceptions of sexuality and likability in initial interactions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 20(16), 1333–1344.

Hass, R. G. (1981). Effects of source characteristics on cognitive responses and persuasion. In R. E. Petty, T. M. Ostrom, & T. C. Brock (Eds.), Cognitive responses in persuasion. Hillsdale, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hayes, A. S., Singer, J. B., & Ceppos, J. (2007). Shifting roles, enduring values: The credible journalist in the digital age. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 22(4), 262–279.

Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communication and persuasion. Yale University Press.

Hu, S., Liu, H., Zhang, S., & Wang, G. (2020). Proactive personality and cross-cultural adjustment: Roles of social media usage and cultural intelligence. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 74, 42–57.

Hughes, C., Swaminathan, V., & Brooks, G. (2019). Driving brand engagement through online social influencers: An empirical investigation of sponsored blogging campaigns. Journal of Marketing, 83(5), 78–96.

Hwang, K., & Zhang, Q. (2018). Influence of parasocial relationship between digital celebrities and their followers on followers’ purchase and electronic word-of-mouth intentions, and persuasion knowledge. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 155–173.

Jabr, W., & Zheng, Z. (2022). Exploring firm strategy using financial reports: performance impact of inward and outward relatedness with digitisation. European Journal of Information Systems, 31(2), 145–165.

Jiménez-Castillo, D., & Sánchez-Fernández, R. (2019). The role of digital influencers in brand recommendation: Examining their impact on engagement, expected value and purchase intention. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 366–376.

Jin, S. A. A., & Phua, J. (2014). Following celebrities’ tweets about brands: The impact of Twitter-based electronic word-of-mouth on consumers’ source credibility perception, buying intention, and social identification with celebrities. Journal of Advertising, 43(2), 181–195.

Jin, S. V., Muqaddam, A., & Ryu, E. (2019). Instafamous and social media influencer marketing. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 37(5), 567–579.

Jin, S. V., & Ryu, E. (2020). ‘I’ll buy what she’s# wearing’: The roles of envy toward and parasocial interaction with influencers in Instagram celebrity-based brand endorsement and social commerce. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102–121.

Johnson, B. J., Potocki, B., & Vedhuis, J. (2019). Is that my friend or an advert? The effectiveness of Instagram native advertisements posing as social posts. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 24, 108–125.

Khamis, S., Ang, L., & Welling, R. (2017). Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of social media influencers. Celebrity Studies, 8(2), 191–208.

Ki, C. W. C., & Kim, Y. K. (2019). The mechanism by which social media influencers persuade consumers: The role of consumers’ desire to mimic. Psychology & Marketing, 36(10), 905–922.

Labrecque, L. I. (2014). Fostering consumer–brand relationships in social media environments: The role of parasocial interaction. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28, 134–148.

Lee, J. A., Sudarshan, S., Sussman, K. L., Bright, L. F., & Eastin, M. S. (2022). Why are consumers following social media influencers on Instagram? Exploration of consumers’ motives for following influencers and the role of materialism. International Journal of Advertising, 41(1), 78–100.

Lee, K. T., & Koo, D. M. (2012). Effects of attribute and valence of e-WOM on message adoption: Moderating roles of subjective knowledge and regulatory focus. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1974–1984.

Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73.

Marwick, A. E. (2013). Status update: Celebrity, publicity, and branding in the social media age. Yale University Press.

Marwick, A. E. (2015). You may know me from YouTube: (Micro-) celebrity in social media. In David Marshall & Sean Redmond (Eds.), A companion to celebrity (pp. 333–350). Wiley.

McCracken, G. (1989). Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(3), 310–321.

McGuire, W. J. (1985). Attitudes and attitude change. In Gardner Lindzey & Elliot Aronson (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 233–246). Random House.

McQuarrie, E. F., Miller, J., & Phillips, B. J. (2012). The megaphone effect: Taste and audience in fashion blogging. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(1), 136–158.

Miller, G. P., & Basehart, J. (1969). Source trustworthiness, opinionated statements, and response to persuasive communication. Speech Monographs, 36(1).

Morhart, F., Malär, L., Guèvremont, A., Girardin, F., & Grohmann, B. (2015). Brand authenticity: An integrative framework and measurement scale. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(2), 200–218.

Moulard, J. G., Garrity, C. P., & Rice, D. H. (2015). What makes a human brand authentic? Identifying the antecedents of celebrity authenticity. Psychology & Marketing, 32, 173–186.

Moulard, J. G., Raggio, R. D., & Folse, J. A. G. (2016). Brand authenticity: Testing the antecedents and outcomes of brand management’s passion for its products. Psychology & Marketing, 33(6), 421–436.

Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 39–52.

Ohanian, R. (1991). The impact of celebrity spokespersons’ perceived image on consumers’ intention to purchase. Journal of Advertising Research, 31(1), 46–54.

O’Mahony, S., & Meenaghan, T. (1997). The impact of celebrity endorsements on consumers. Irish Marketing Review, 10(2), 15–24.

Ratten, V., & Tajeddini, K. (2017). Innovativeness in family firms: An internationalization approach. Review of International Business and Strategy, 27(2), 217–230.

Schouten, A. P., Janssen, L., & Verspaget, M. (2021). Celebrity vs. influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and product–endorser fit. In Leveraged marketing communications (pp. 208–231). Routledge.

Schouten, H. J., Tikunov, Y., Verkerke, W., Finkers, R., Bovy, A., Bai, Y., & Visser, R. G. (2019). Breeding has increased the diversity of cultivated tomato in the Netherlands. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10, 1606. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01606

Serazio, M. (2015). Selling (digital) millennials: The social construction and technological bias of a consumer generation. Television & New Media, 16(7), 599–615.

Shepherd, D. A., & Zacharackis, A. 2003. A new venture’s cognitive legitimacy: An assessment by customers. Journal of Small Business Management, 41(2), 148–167.

Sokolova, K., & Kefi, H. (2020). Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53, 101742.

Sokolova, K., & Perez, C. (2021). You follow fitness influencers on YouTube. But do you actually exercise? How parasocial relationships, and watching fitness influencers, relate to intentions to exercise. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102276.

Stubb, C., Nyström, A. G., & Colliander, J. (2019). Influencer marketing: The impact of disclosing sponsorship compensation justification on sponsored content effectiveness. Journal of Communication Management, 23(2), 109–122.

Tafesse, W., & Wood, B. P. (2021). Followers’ engagement with Instagram influencers: The role of influencers’ content and engagement strategy. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102303.

Taylor, C. (1991). The ethics of authenticity. Harvard University Press.

Tellefsen, T., & Thomas, G. P. (2005). The antecedents and consequences of organizational and personal commitment in business service relationships. Industrial Marketing Management, 34(1), 23–37.

Thakur, S., Singh, L., Wahid, Z. A., Siddiqui, M. F., Atnaw, S. M., & Din, M. F. M. (2016). Plant-driven removal of heavy metals from soil: uptake, translocation, tolerance mechanism, challenges, and future perspectives. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 188, 1–11.

Van der Toorn, J., Tyler, T. R., & Jost, J. T. (2011). More than fair: Outcome dependence, system justification, and the perceived legitimacy of authority figures. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(1), 127–138.

Van der Waldt, D. L. R., Van Loggerenberg, M., & Wehmeyer, L. (2009). Celebrity endorsements versus created spokespersons in advertising: A survey among students. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 12(1), 100–114.

Wang, S. W., & Scheinbaum, A. C. (2018). Enhancing brand credibility via celebrity endorsement: Trustworthiness trumps attractiveness and expertise. Journal of Advertising Research, 58(1), 16–32.

Wang, T., Song, M., & Zhao, Y. L. (2014). Legitimacy and the value of early customers. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(5), 1057–1075.

Wathen, C. N., & Burkell, J. (2002). Believe it or not: Factors influencing credibility on the Web. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(2), 134–144.

Wei, K. K., & Li, W. Y. (2013). Measuring the impact of celebrity endorsement on consumer behavioural intentions: a study of Malaysian consumers. International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, 14(3), 157–177.

Weismueller, J., Harrigan, P., Wang, S., & Soutar, G. N. (2020). Influencer endorsements: How advertising disclosure and source credibility affect consumer purchase intention on social media. Australasian Marketing Journal, 28(4), 160–170.

Wojdynski, B. W., & Evans, N. J. (2016). Native: Effects of disclosure position and language on the recognition and evaluation of online native advertising. Journal of Advertising, 45(2), 157–168.

Zimmerman, M. A., & Zeitz, G. J. 2002. Beyond survival: Achieving new venture growth by building legitimacy. Academy of Management Review, 27(3), 414–431.